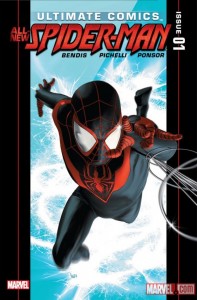

Ultimate Spider-Man #1-#3 (Nov.-Dec. 2011). Brian Michael Bendis, writer. Sara Pichelli, artist.

I first met Spider-Man not in comic books, but on the TV screen. It wasn’t the 1960s cartoon with the catchy song; no, I’m talking Spider-Man, 1970s PBS style! I was one excited little six-year-old as I waited through each episode of The Electric Company (where God—oops, I mean, Morgan Freeman—launched his career) for this magic moment:

Dig that groovy tune! “Spider-Man, where are you coming from, Spider-Man? Nobody knows who you are!” And it was true: on The Electric Company, we never heard (or read) a word about Peter Parker. Spidey was just Spidey. It never occurred to me to ask about the person behind the mask.

(Incidentally, did this segment’s baddie, The Wall, terrify anyone else out there back in the day, or just me?)

Over 30 years later, people are again asking, “Where are you coming from, Spider-Man?” Marvel Comics attracted a lot of attention in August when it revealed a new Spider-Man. As Forbes magazine blogger Matthew Newton documented, most “mainstream media outlets chose to frame the news” of new character Miles Morales “with some form of ‘half-black, half-Latino’ or ‘half-black, half-Hispanic’ in the headline.”

While most news reports struck an even-handed tone, not all opinion pieces did. An LA Weekly blog dismissed the character as “PC,” asking, “Does this reek of desperate, hasty diversification for the sake of superstar PR?” Glenn Beck even declared at great length just how much he really and truly does not care about the new Spider-Man’s ethnicity (and sexuality; a comment from artist Sara Pichelli sparked apparently baseless speculation that Miles may be gay)—before going on to insinuate that Miles is one part of some larger, revisionist cultural agenda orchestrated by the Obama administration.

Some I nternet comments generated almost as much controversy as Miles himself—for example, the USA Today reader who declared, “A black boy under the mask just don’t look right.” Lest you think this concerned comics consumer possesses x-ray vision, he or she clarifies that objection with the rhetorical question: “Who is going to believe a black man in a mask is out for the good of man kind?” [sic].

nternet comments generated almost as much controversy as Miles himself—for example, the USA Today reader who declared, “A black boy under the mask just don’t look right.” Lest you think this concerned comics consumer possesses x-ray vision, he or she clarifies that objection with the rhetorical question: “Who is going to believe a black man in a mask is out for the good of man kind?” [sic].

In response, other comments, posts, and essays argued that the new hero’s race simply doesn’t matter. Regular comic readers—the ones who weren’t just picking up the book because it was trending on Twitter—reminded the uninitiated that Miles will be Spider-Man only in Marvel’s “Ultimates” continuity. In the normative, “Earth-616” universe, Peter Parker is still your friendly neighborhood Spider-Man. (Of course, “assurances” such as that found in an Entertainment Weekly blog, that “This isn’t the ‘real’ Spider-Man,” raise new problems. Is it only all right to have a non-white Spider-Man if he doesn’t “really count?”)

Other defenders of Marvel’s move praised it as a triumph for inclusion and multiculturalism. In part, Marvel has tried to spin the new web-spinner this way: EIC Axel Alonso told CNN, “When the opportunity arose to create a new Spider-Man, we knew it had to be a character that represents the diversity—in background and experience—of the 21st century.”

I appreciate the good intentions behind claims that this new Spider-Man’s race really doesn’t matter. But in the end, it does. Not because it’s some supposed thumbing of Marvel’s nose at the past; and not because it’s some nefarious plot to rewrite cultural icons; and not because it’s some ostensible breakthrough for diversity in superhero comics. Miles’ race matters simply because it’s a part of his story, as race is for each one of us. It’s one of his particulars—and Christians believe that we must deal with people not in general but in particular, because that is how God deals with us.

Linus—that august philosopher from Charles Schulz’ Peanuts—once declared, “I love mankind. It’s people I can’t stand!” It’s easy to love humanity in the abstract. What’s harder is loving the individual men, women, and children whose paths cross ours, against whom we jostle on the sidewalk or in the subway car, who sit next to us in the classroom or the cubicle, even with whom we live under one roof.

Yet Jesus commands us to do just that: to love, not humanity in general, but our neighbor in particular (Mark 12.31). That’s how God loves us. God loved the world, but God didn’t stop at thinking nice thoughts about the human race en masse, or even saving humanity at a distance, with a wave of the divine hand. The Word became flesh—the particular flesh of a first-century, Palestinian Jewish carpenter-turned-itinerant rabbi who was executed as a common criminal. “This Jesus,” and none other, “God raised up… [and] made him both Lord and Messiah” (Acts 2.32, 36).

Do Jesus’ ethnicity and cultural background matter? Not ultimately (no Marvel publishing pun intended). The doctrine of the Incarnation is not primarily about Jesus’ Jewishness, or his language, or his gender, or his appearance (and we might infer from Isaiah’s prophecies of him that he was no looker—Isa. 53:2). What’s at stake is that Jesus was really and truly human. Since we “share flesh and blood, [Jesus] himself likewise shared the same things” (Heb. 2.14).

But you can’t share flesh and blood in the abstract. To the degree they confirm Jesus was not only fully divine but also fully human, and therefore fully capable of saving us, his ethnicity and cultural background and all the other attributes do matter. (And we forget these attributes at our peril. Centuries of Western Christianity’s willful amnesia about Jesus’ Jewish identity, after all, helped make the Holocaust possible.)

Jesus was a real person, calling us to love other real people, and to engage with them in all of their often complicated particularities. If the fuss over Miles Morales has any lesson for life outside of comic books, maybe it’s this: We aren’t free to reduce anyone to one or two of their attributes. If we call Miles “the black Spider-Man,” or even “the half-black, half-Latino Spider-Man,” we reinforce lazy ways of thinking about people and potentially cruel ways of classifying them. We think we’ve said all there is to say. Yes, I know Miles is make-believe—but if appreciating literature in any way prepares us for living life, it should prepare us to know and appreciate and love people as people, for that is how God knows and appreciates and loves us. With the apostle Paul, we profess faith in the one “who loved me and gave himself for me” (Gal. 2.20, emphasis added)—not me alone, but no less me.

Jesus was a real person, calling us to love other real people, and to engage with them in all of their often complicated particularities. If the fuss over Miles Morales has any lesson for life outside of comic books, maybe it’s this: We aren’t free to reduce anyone to one or two of their attributes. If we call Miles “the black Spider-Man,” or even “the half-black, half-Latino Spider-Man,” we reinforce lazy ways of thinking about people and potentially cruel ways of classifying them. We think we’ve said all there is to say. Yes, I know Miles is make-believe—but if appreciating literature in any way prepares us for living life, it should prepare us to know and appreciate and love people as people, for that is how God knows and appreciates and loves us. With the apostle Paul, we profess faith in the one “who loved me and gave himself for me” (Gal. 2.20, emphasis added)—not me alone, but no less me.

In Part 2, we’ll look at who we meet when we meet Miles Morales in particular, and think about how his particulars might shape our attitudes toward our own.

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version.

I think one of the inspirations for this was the fan effort to get Donald Glover cast as Peter Parker in the new Spider-man movie.

Budd, I ran across that, yes. I am embarassed to admit I didn’t really know who Donald Glover was before that! Supposedly, Bendis had already created the character of Miles, and said that the attention to Glover’s campaign for the part “confirmed” his instincts (see http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/08/02/new-ultimate-spider-man-half-black-half-latino_n_916468.html). Have you been reading the series? Miles is an interesting character with a rich backstory — I get into more of that in part 2 of this article (coming soon!). Thanks for reading and commenting!