On a couple of recent editions of the podcast, Matt and I have debated the role of subjectivity and objectivity in judging greatness in art. Matt holds that it’s impossible to determine greatness objectively, while I take the opposite view.

Our discussion of LOST was the starting point for the debate, but the question is far more philosophical than that. For that reason, I appreciated a piece of listener feedback sent in this week from listener Skip. The call, which we’ll play in its entirety on the next show, pushes the argument in a more philosophical direction. Skip agrees with Matt on the basis that the criteria used in determining aesthetic greatness are entirely subjective. Two people may disagree on which show, book or piece of art is the greatest due to the fact that they are using different criteria. Those criteria are a matter of personal opinion, therefore aesthetic judgments are subjective.

It’s a well-made argument and one that deserves more of a response than I would be able to give during our listener feedback section. For that reason, I’ve decided to respond here. Fair warning: I’m going to get fairly philosophical in this article. Those of you who don’t want to risk flashbacks to your Sophomore Intro to Philosophy class may want to bail out now!

To start things off, let me be clear about what I’m NOT arguing. When I claim that it’s possible to make objective statements about aesthetics, I am not claiming that we can reduce aesthetic judgments to a simple formula in which we plug in a few criteria and are then able to rank works of art.

I’m reminded of the scene in Dead Poets Society where Robin Williams’ character mocks exactly that sort of system. He presents to his class the Pritchard Scale – a means of graphing a poem’s perfection and importance in an effort to simplistically determine its greatness. The film presents the method as absurd, and appropriately so! It is a dry, mechanical, lifeless approach to art. If that is what we assume is meant by aesthetic objectivity than we have no choice but to side with Skip on the subjective side of the argument.

The problem is that the subjective side becomes equally absurd. Allow me to demonstrate the principle with several extreme examples:

If we assume aesthetic judgments are entirely subjective then it is impossible to claim that Hamlet is a superior work to Dumb and Dumber. We have no basis to claim that the “To Be or Not To Be” soliloquy is greater than a scene involving Jeff Daniels having explosive diarrhea. Remember, we’re not talking about preference here. There are many people who may enjoy watching Jeff Daniels experience digestive problems while finding Shakespeare confusing and unenjoyable. Preference is subjective; however, when we put preference aside, are we able to objectively say that Hamlet is greater than a low brow comedy? Absolutely! It would be absurd not to!

Let’s take things one step further. If aesthetic judgments are entirely subjective then there is no objective basis to claim that a film such as Schindler’s List is artistically greater than a porno. We may object to the morality present in pornography, but we cannot object to its aesthetic value. According to the subjective argument, if I claim Schindler’s List is better, it is because of the criteria I am using. Since that criteria is subjective, the most I am able to say is that I personally believe Schindler’s List is of higher aesthetic quality than porn but I must concede that it is not actually any better or worse aesthetically than porn.

But, of course, that sort of statement is absurd. Everything inside of us recoils at what it suggests, and appropriately so. On the one hand we have one of the most powerful films, crafted with excellence, with a profound message about human sacrifice and on the other we have a film where the only goal is sexual exploitation. If we have any sort of intellectual integrity, we ought to be able to clearly see that the one far surpasses the other!

Here is a third example for those who may claim my others are invalid due either to genre differences or differences of intent. We ought to be able to objectively state that The Dark Knight is a superior film to Batman and Robin. The suggestion seems right and most of us would agree, but how do we establish it objectively? One is an exploitive mess filled with bad acting and a poorly directed disaster of a plot. The other is a meaningful exploration of heroism, terrorism and escalation, to name but a few of the many themes that Christopher Nolan’s film explores.

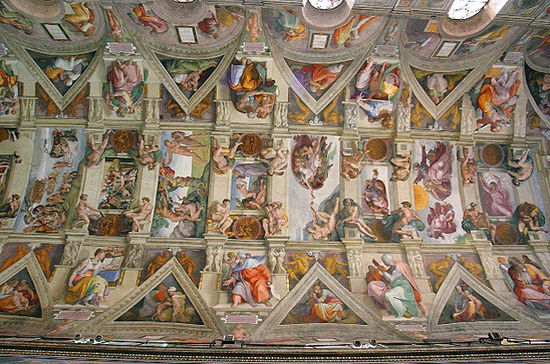

One final example I’ll throw in, if for nothing more than my own amusement: I am utterly talentless when it comes to drawing. I can barely manage stick figures. However, if the subjective argument is correct, it is impossible for anyone to say that my stick figure art is any less great than Michelangelo’s “The Sistine Chapel.” I assure you that it is! I can objectively state that there are light-years of difference between the quality of my work and that of Michelangelo!

The problem, then, with the subjective argument put forward by Skip, Matt and others in their camp is that it is unable to make any of the painfully obvious distinctions outlined above. The closest it can get would be to say that nearly everyone, everywhere could agree that one is greater than the other; but ultimately, that is still a matter of personal opinion. I find that position utterly unworkable, and, in the case of the Schindler’s List example, somewhat horrifying.

It would seem that we are caught between a rock and a hard place. On the one hand we have the rigid stupidity of the Pritchard Scale. On the other we have a system where even the most obvious judgments are unable to be made. What is left to us as a viable alternative?

Actually, quite a bit. The two systems outlined above are not the only options and, in fact, both share the same fatal flaw. Both systems represent post-enlightenment, western thought. The Pritchard Scale comes from a modernist perspective; the subjective argument from a post-modern one.

Both make the mistake of placing the individual at the center of aesthetic judgments through their undue faith in man’s reason and intellect. The modernists see art as something that can be tamed and experimented on. It is something that we can, metaphorically speaking, place under a microscope and dissect. Anyone who has ever experienced true aesthetic beauty or excellence knows that’s not the case. You cannot tame true art. You can only stand in awe of it and hope, by some measure, to have it change you so that you might in some small way be able to better understand it.

By the same token, our post-modern friends also place the individual at the center. Here, it is not reason and intellect that are elevated unduly, but personal opinion. The effect, however, is the same. The modernist expects art to bow before his abilities. The post-modernist expects it to bow before his opinions. Both have failed to understand what aesthetics truly are.

What, then, is the alternative? First, we must realize that when we seek to explore aesthetics we are seeking to experience that which is foreign to us. We are not at the center of an artistic experience. To truly appreciate art we must submit ourselves to it, not the other way around. We do not come to conquer (modernism) or control (post-modernism). We come to experience.

Second, and this is perhaps the most important point, we must realize that aesthetics are a part of the created order. This point is, obviously, derived from my Christian worldview. I believe that when God pronounces creation “good,” he is not referring only to its utilitarian quality. He is, at least in part, referring to its aesthetic excellence. In other words, God created beauty and excellence and he judges creation with his aesthetic answer.

That ought to give us, with our post-enlightenment mindset, pause. When we experience art, we are experiencing a part of God’s creation. Like other parts of creation, it will impact different people in different ways. However, it would be incorrect to imply that any part of a creation is entirely subject to individual judgments. It exists beyond us. Its standard was set before we were in the picture.

To look at art only through the lens of personal preference, as the subjective argument ultimately requires us to, is too small of a view. We will never experience the full greatness of this part of God’s creation so long as we have placed ourselves at the center of it.

Third, if we understand that the aesthetic standard is something that exists objectively beyond us, how are we to avoid falling back into the trap of the Pritchard Scale? In other words, it may seem that we are back to square one. Having established that there is a standard put forward by God, are we then back to judging art through a rigid and basic formula?

To put it simply, no. The Pritchard Scale is simplistic. What I am talking about is of immense complexity. We are seeking to understand something that originates in God, and therefore we will never be able to completely understand it. It would be impossible to develop an exhaustive list of objective criteria.

Does that mean that we practically find ourselves in line with the subjective camp? Perhaps there is an objective standard, but since we are unable to fully grasp it, are we unable to make truly objective arguments? Again, the answer is no. Even without perfect understanding, we find ourselves able to make meaningful aesthetic judgments, such as in the examples above. I do not need to perfectly understand the objective criteria in order to be able to say that Schindler’s List is of greater artistic excellence than a porn film. In short, we may be unable to make perfect judgments, but the solution is not to wave the white flag and retreat to the subjectivist’s corner.

So why does any of this matter? In terms of Matt and my original discussion on the greatest television show, it matters very little. Ultimately, I don’t think LOST has to many problems being established as the greatest show ever, but perhaps Matt will surprise me someday with a strong objective argument to the contrary. I think it’s unlikely, but given the complexity I’ve just described, it can’t be entirely ruled out.

In terms of our faith, however, this conversation matters greatly. Depending on how we measure it, as much as 70-80% of the Bible is narrative or poetic! I find it highly significant that God chose art to communicate the majority of his Word to us.

I would argue that so long as we take a man-centered approach to aesthetics, we’re going to miss a significant portion of what God’s trying to say. That doesn’t mean that those who disagree with me are bad Christians. Far from it! It does mean that in order to properly understand biblical aesthetics, we must first see them as something that originates in God and not as something that is subject to ourselves.

I’ve already gone far too long for a blog post, so let me close by challenging us to approach art in exactly that way. Don’t look at stories, music, paintings or anything else as things that are subject to your personal opinions. Preferences are fine and they have an important place but they don’t take us far enough. Instead, approach art as an opportunity to hear God and experience him. It originates with him, not you. I believe he has great, objective truths to communicate to us through it.

i think i mostly agree with your opinion, Ben, in that i’m probably more of the mind that God set the standard for beauty. but, to play devil’s advocate for a minute, i can still sympathize with the subjectivist point of view. if i were to argue this, i would say that your points about comparing or contrasting Dumb and Dumber to Hamlet or Schindler’s List to a porno might be exactly what they are talking about. as a person who has little interest in Shakespeare, Dumb and Dumber IS better than Hamlet to me. i could name a dozen other people who would say the same thing, and would talk about how much fun they’ve had quoting the stupidest lines from that movie while all they remember from Hamlet was how sleepy they were in English class. i’m betting that a subjectivist might say that art is subjective because we judge it by what is more meaningful to us personally. and that we discern and derive meaning from things from our own subjective experiences. just because something like Hamlet appeals to a commonality in people’s subjectivity doesnt necessarily prove that Hamlet is objectively better than Dumb and Dumber. but that’s just what i’d say if i were debating. lol. i side with God’s Opinionism. 🙂

I agree that that sort of reasoning would be where the subjectivist argument would go. The problem I see with it is that it confuses preference with excellence. To make that argument you have to establish that they are the same. Based on my worldview whereby God sets the standard for aesthetic excellence, I have to conclude it’s invalid. That’s a presuppositional argument and won’t convince everyone, which I’m more than ok with. My point is that I don’t think the Bible is silent on the subject of aesthetics therefore making the subjectivist argument invalid for those of us holding to a biblical worldview

great point! 😀

Great post, Ben, and lots to think about. My immediate reaction, though, is that, while I agree that “God sets the standard for aesthetic excellence,” I disagree with your contention that “When we experience art, we are experiencing a part of God’s creation” and art “originates with him [i.e, God], not you.” The two points are not the same.

Yes, God sets the standard for what is beautiful, true, just, pleasing, praiseworthy (Phil. 4). But God does not write either “Hamlet” or “Dumb and Dumber.” God does not direct and film “Schindler’s List.” And, frankly, in my view of the Bible, God doesn’t even dictate the psalms. God can and does inspire artists, but I think it confuses the issue to claim that their creations are, therefore, God’s. (Biblical inspiration is a special case, since the same Spirit that inspired the speaking or writing of those texts uses them still to speak God’s living Word; but, even there, the human authors of Scripture did not have their individual voices and creativity and artistry stripped away. The Bible is not the Qur’an, which Muslims hold to be the dictated word; rather, it is the inspired word).

So, when I’m reading Shakespeare or watching Spielberg or listening to Bach or whatever, I’m only “experiencing a part of God’s creation” in a derivative sense; i.e., I am seeing the end results of the creative abilities that God gave to human beings — and gave graciously, meaning both “freely” and “not needing to take away the credit”! Perhaps this is what you meant; but as I read your post, the point seemed to come up several times, so I thought it bore pointing out.

Overall, though, I agree: the Bible is not silent on aesthetics. We are told that God is a craftsman, a builder, a potter — many images and metaphors and descriptions of God’s creative activity. So, if we want to know, objectively, good art, we must look to the works of the Great Artist and draw our conclusions from them, not from our own, subjective likes and dislikes.

Thanks again for this post!

Good point Mike. When I say that art is a part of God’s creation and originates with him, I’m referring to art (and aesthetics) in a conceptual, philosophical sense, not a specific sense. To put it more accurately, the concept of art (and therefore aesthetic standards) originate with God and are part of the created order.

You’re right – When an artist creates his creation is his own. However, it’s important we not stop there because in that creation he is participating in something that is not his own, that being the very concept of art which has been created by God.

I agree with you that credit need not be taken away from artists, but I do think it’s important that all art be recognized within a broader context than the individual.

Yeah, as I reflected more after posting, I don’t think we’re that far apart. I can agree with the idea of art, even the artistic impulse and endeavor, as something God has given humans to do. God invites and equips us to become creators ourselves (in a derivative sense — Tolkien has a lot to say about this in “On Fairy-story”).

So, bringing in the old question of whether we “make” meaning or merely “discover” meaning, would Ben’s position align with the latter?

It’s an interesting question and one I’d need to give more thought to, but my initial reaction is, yes, we discover meaning; we do not create it. Obviously things get much more complex when we consider our role as God’s stewards over creation and, in a sense, his co-creators. But at a high level, I’d lean more in the discovery direction

It’s easy to say “Obviously ‘Dumb and Dumber’ is better than Shakespeare”, but what are you basing this on, other than societies heightened regard for Shakespeare? Is Shakespeare more complex, more highbrow? Does it deal with more challenging concepts and, perhaps, better represent what humankind believes is important to life? Yes. These are all things that can be said. But you cannot make the statement that these make it BETTER, because now you have crossed into the realm of opinion.

Is Bach better than Bruce Springsteen? No. Is Bruce better than Lady Gaga? No. Bach is more complex, is more widely studied, but when people try to say his work is BETTER, they end up just trying to argue that their tastes (which are often INHERITED through reinforcement), are somehow a logically justified knowledge of reality.

It’s not.

Many people will disagree, because many people have been brought up to believe that Monet, Michelangelo, Ravel, Beethoven, and so on, have some “objective quality of goodness”, but they simply appeal more to popular opinion of “what goodness is”. It’s a flaw in our education system (which doesn’t itself understand aesthetics) that lead us to believe that our opinions are attempts to access an objective truth.

Sorry about the spelling errors:

*society’s

*They’re not

*leads us to…