How do you celebrate Christmas in the Twilight Zone?

Long-time fans of Rod Serling’s classic series will think of “Night of the Meek,” the heartwarming story first broadcast in 1960 (and recently referenced right here on the Sci-Fi Christian), in which a drunken ex-department store Santa Claus gets a second chance (and then some!) at Christmas.

But there’s another Yuletide excursion into that “land of both shadow and substance.” Where “Night of the Meek” is a fantasy that tugs at the heartstrings, this episode (which first aired as part of the 1980s Twilight Zone revival, on December 20, 1985) is science fiction that engages the mind and even challenges the spirit. It’s a perfect counterpart to the earlier story—in fact, it aired as part of a Christmas episode that includes a remake of “Night of the Meek”—and is one of the revived Zone’s most memorable installments.

But there’s another Yuletide excursion into that “land of both shadow and substance.” Where “Night of the Meek” is a fantasy that tugs at the heartstrings, this episode (which first aired as part of the 1980s Twilight Zone revival, on December 20, 1985) is science fiction that engages the mind and even challenges the spirit. It’s a perfect counterpart to the earlier story—in fact, it aired as part of a Christmas episode that includes a remake of “Night of the Meek”—and is one of the revived Zone’s most memorable installments.

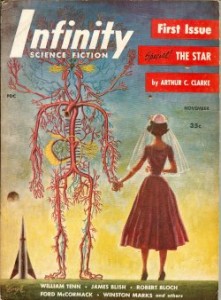

“The Star” is based on a short story by Arthur C. Clarke. In his tale (first published in Infinity Science Fiction, November 1955), we meet an unnamed Jesuit priest who is also an astronomer and physicist. He is serving on an expedition to the Phoenix Nebula: “to visit the remnants of such a catastrophe, to reconstruct the events that led up to it, and, if possible, to learn its cause.”

What the crew learns is that, despite all expectations, a planet bearing intelligent life once circled the now-exploded star. Facing their doom, this race placed all of its culture’s literary, artistic, and philosophical treasures in a fortified structure that the humans dub, “the Vault.” As the priest says, “A civilization that knew it was about to die had made its last bid for immortality.”

The images and objects in the Vault make it clear that this alien race was full of “warmth and beauty… [and] in many ways must have been superior to our own.” This sad discovery profoundly moves the crew:

Many of us had seen the ruins of ancient civilizations on other worlds, but they had never affected us so profoundly. This tragedy was unique. It is one thing for a race to fail and die, as nations and cultures have done on Earth. But to be destroyed so completely in the full flower of its achievement, leaving no survivors—how could that be reconciled with the mercy of God?

The Jesuit tries to cling to his faith, invoking such arguments as, “God has no need to justify His actions to man.” But his faith falters—irrevocably, I think Clarke leads us to believe—when his calculations prove that the exploded star’s light would have reached Earth exactly in time to shine as the Star of the East seen by the Magi. At the end of the story, our man of science and former man of faith is agonizing over this question: “Yet, oh God, there were so many stars you could have used. What was the need to give these people to the fire, [that] the symbol of their passing might shine above Bethlehem?”

Clarke’s story is brief and elegant. For all the potential power of its theological “punchline,” however, “The Star” is slight, largely due to the fact that the viewpoint character is not fully developed. What we know of him, we know only because he tells us. His credentials as a man of science are firmly established, including his publications and his admirable commitment to telling truth; but we do not get to know him as a believer. His frequent declarations that he is experiencing a crisis of faith—e.g., “But there comes a point when even the deepest faith must falter, and now… I know I have reached that point at last”—don’t convince. This lack of emotional heft may be because we have no chance to observe his faith for ourselves. The story begins and ends with him in spiritual turmoil. Had Clarke given us some glimpse of that time when the character believed, as he tells us he once did, “that space could have no power over faith,” we might feel the loss the character insists he feels. Instead, the story leaves readers cold. And perhaps this is Clarke’s intent: after all, our nameless protagonist now views the universe as a cold and callous place, with no Creator to care for it.

Clarke’s story is brief and elegant. For all the potential power of its theological “punchline,” however, “The Star” is slight, largely due to the fact that the viewpoint character is not fully developed. What we know of him, we know only because he tells us. His credentials as a man of science are firmly established, including his publications and his admirable commitment to telling truth; but we do not get to know him as a believer. His frequent declarations that he is experiencing a crisis of faith—e.g., “But there comes a point when even the deepest faith must falter, and now… I know I have reached that point at last”—don’t convince. This lack of emotional heft may be because we have no chance to observe his faith for ourselves. The story begins and ends with him in spiritual turmoil. Had Clarke given us some glimpse of that time when the character believed, as he tells us he once did, “that space could have no power over faith,” we might feel the loss the character insists he feels. Instead, the story leaves readers cold. And perhaps this is Clarke’s intent: after all, our nameless protagonist now views the universe as a cold and callous place, with no Creator to care for it.

In adapting Clarke’s story for the small screen, veteran TV and comics writer Alan Brennert had the advantage of being able to give the story’s unnamed narrator a name and a face. As played by Fritz Weaver (who, as part of his long career, guest starred twice on the original Zone), Father Costigan meets us in the first scene as a man with a lively and even joyful faith, standing on the ship’s observation deck and proclaiming the starscape before him wondrous evidence of God’s creative handiwork. Dr. Chandler, played by Donald Moffat, joins him and presents a rationalist’s view of the universe as evidence of randomness, not design. The the two men, however, have obvious affection for each other. The scene makes Costigan a more fully developed character—and makes his crisis of faith at the story’s end more powerful.

It is at the episode’s end that Brennert introduces a note of hope not present in his source material. (In his DVD commentary on the episode, he claims he angered a lot of Clarke purists!) The new scene plays a bit saccharine, but it hit me hard when I first watched it as a teen, and I still think it offers a lot to ponder. The aliens’ final poem, in particular, seems worthy of close attention:

Mourn not for us, for we have known the light,

And looked on beauty and lived in peace and love.

Grieve but for those who go alone, unwise,

And die in darkness and never see the sun.

This text Brennert wrote for the aliens intrigues me. What layers of meaning might lie in the phrase, “we have known the light”? Did they know only the fulfillment and peace that can come from a society’s own efforts? Or is it possible that they knew not only that light but also The Light—“the true light, which enlightens everyone” (John 1.9)? It’s pure speculation on my part, of course—but hopeful speculation. In the book of Acts, the apostle Paul preaches that “the living God, who made the heaven and the earth and the sea and all that is in them… has not left himself without a witness in doing good—giving you rains from heaven and fruitful seasons and filling you with food and your hearts with joy” (Acts 14.15, 17). The aliens in the televised version of “The Star” seem to have known and enjoyed such goodness; and since I believe all goodness is ultimately a gift from God, I can’t help but wonder if their epitaph bears witness to their own, unique relationship to The Light.

Our world’s unique experience of The Light comes through Jesus of Nazareth. The aliens’ poem also makes me think of the promise that begins John’s gospel, the promise at the heart of Christmas: The Light, the Word of God, “became flesh and lived among us, and we have seen his glory” (John 1.14). Pointing to God’s light in Jesus does not, of course, easily answer questions of suffering and injustice such as those that Father Costigan raises. But God has given us something better than an answer: God has, in Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection, made us a promise, a pledge, that “the light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it” (John 1.5, NIV), and never can.

As Christians, we have, to borrow the aliens’ phrase, “known the light.” The apostle John models how we are to respond: “This is the message that we have heard from him and proclaim to you, that God is light and in him there is no darkness at all” (1 John 1.5). We are to share the good news that, no matter what darkness swirls around and within us, the gracious light of God’s love in Jesus can penetrate it. As Dr. Chandler suggests to Father Costigan, we can “light the way” for others, because God in Christ has lit the way for us.

May you find your way lit by the love of Jesus, this Christmas, in the New Year, and always!

Except where noted, all Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version.

Thank you for the write up Michael! It’s always intriguing to me to hear about and read older sci-fi stories because on the whole they seem to tackle philosophical/theological issues to a much greater degree than current narratives (though I must admit I enjoy the contemporary ones with all their action and thrills ;)).

Also, reading your post made me think of one of the short stories in Ray Bradbury’s collection The Illustrated Man where two priests journey to Mars to spread the Gospel but find that the Martians are made of pure energy, so the priests wrestle with the apparent absence of sin from the alien beings.

Anyway thank you again and Merry Christmas!

Thanks for reading and commenting, Francisco.

I have to admit, I don’t read as much current sf as I would like. I wonder if the literary side of the genre still isn’t just as preoccupied with those philosophical and theological issues you mention as the stories of yesteryear. One (fairly) recent novel I read that had clear theological overtones was “Passages” by Connie Willis. Unless I miss my guess, the symbolism she uses — gently, subtly, but it’s there — suggests that she may be a Christian.

I love Bradbury’s stuff! I don’t think I’ve read the story you mention, though, although I do like “The Man,” where a rocket captain is going from planet to planet searching for Jesus, only to discover that he keeps just missing him. I think it turns out he has too many preconceptions about who Jesus can and can’t be, or who Jesus would and wouldn’t care about — so that’s got some obvious lessons for Jesus’ followers in the real world.

Merry Christmas to you and yours, also!

Great article, Michael. Looking forward to checking out this episode.

Thanks, Max. I’d like to know what you think of it once you see it.