Tomorrow, December 17, is the feast day of Saint Lazarus, at least according to some versions of the Roman Catholic calendar of saints’ days. “Lazarus” is not a name you easily forget. Readers of the New Testament will remember not one, but two men named Lazarus: one fictional, the other factual.

Tomorrow, December 17, is the feast day of Saint Lazarus, at least according to some versions of the Roman Catholic calendar of saints’ days. “Lazarus” is not a name you easily forget. Readers of the New Testament will remember not one, but two men named Lazarus: one fictional, the other factual.

Jesus told a story (Luke 16.19-31) about a poor beggar named Lazarus, who languished outside the locked gates of a rich man, his only companions the stray dogs that licked his open sores. When Lazarus died, angels carried him “into Abraham’s bosom” (v. 22, KJV), to rejoice with the patriarch in heaven. In contrast, when the rich man died, he was consigned to eternal flames. He begged Abraham to send Lazarus to comfort him with even one drop of cool water, but Abraham replied, “Child, remember that during your lifetime you received your good things, and Lazarus in like manner evil things” (v. 25). The fictional Lazarus represents the all-too-real suffering of so many people in poverty; and Jesus’ parable remains a stark warning to those who are content to enjoy comfort at the expense of the poor.

The factual Lazarus was Lazarus of Bethany, brother to Mary and Martha. This Lazarus also dies—but, in the last great sign he performs before his crucifixion, Jesus raises Lazarus to life, dramatically calling him from his tomb (John 11.38-44). Lazarus’ resuscitation, his miraculous return to earthly life, serves as a sign of resurrection: the qualitatively new and unending life that Jesus promises to those who believe in him: “I am the resurrection and the life. Those who believe in me, even though they die, will live, and everyone who lives and believes in me will never die” (John 11.25-26).

Saint Lazarus’ Day is intended to honor the Lazarus whom Jesus raised from death, although sometimes, thanks to conflation, the leprous beggar is also remembered on this day (as, for example, in Cuba). Of course, since I am not only a Presbyterian but also a geek, when I hear the name “Lazarus,” my first thought is just as likely to be of neither the revived brother nor the run-down beggar, but of one of the name’s several occurrences in science fiction. (Like I said, it’s not a name you easily forget!)

On this eve of Saint Lazarus’ Day, let’s count down my top five Lazaruses (Lazarae? Lazarii?) in sci-fi. We just may discover a few connections to the biblical ones along the way. (By the way, this list does not claim to be exhaustive! Feel free to add your own favorite sci-fi Lazaruses—Lazarim? Lazarot?—in the comments!)

5. Lazarus Long (recurring Robert A. Heinlein character, first introduced in Methuselah’s Children, 1958)

No doubt Heinlein devotees will fault me for placing this classic character so far down on my list. I can only plead that I’ve read embarrassingly little Heinlein—far less than any respectable science fiction fan should—and none of it featuring this pivotal person in Heinlein’s elaborate “Future History” and, according to The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, Heinlein’s “final—and most enduring—alter ego” (p. 556). Neil Barron’s assessment of the character (in his capsule review of Heinlein’s 1973 novel Time Enough for Love) seems to strike a somewhat more critical note: “An extravagant exercise in the production of an idealized fantasy self, drawing on the repertoire of science fiction ideas to support and sanction an extraordinary form of imaginary self-indulgence” (Anatomy of Wonder, 5th ed., 2004, p. 237).

No doubt Heinlein devotees will fault me for placing this classic character so far down on my list. I can only plead that I’ve read embarrassingly little Heinlein—far less than any respectable science fiction fan should—and none of it featuring this pivotal person in Heinlein’s elaborate “Future History” and, according to The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, Heinlein’s “final—and most enduring—alter ego” (p. 556). Neil Barron’s assessment of the character (in his capsule review of Heinlein’s 1973 novel Time Enough for Love) seems to strike a somewhat more critical note: “An extravagant exercise in the production of an idealized fantasy self, drawing on the repertoire of science fiction ideas to support and sanction an extraordinary form of imaginary self-indulgence” (Anatomy of Wonder, 5th ed., 2004, p. 237).

Whether Long is all that bad, I can’t judge. He does appear to be a colorful, larger-than-life character—altogether fitting, considering that he is the result of a generations-long program of selective breeding with a lifespan covering at least two centuries. He is also a time traveler. Long wasn’t afraid to rush in where Marty McFly was afraid to tread and actively seduced his own mother—not, I’m told, resulting in his own conception. Because that would’ve been wrong.

Long is known for numerous bon mots that readers generally take to represent Heinlein’s opinions. Some of Long’s particularly pithy proverbs? Browsing the web, I immediately liked both “An elephant is a mouse built to government specifications,” and, “Being intelligent is not a felony, but most societies evaluate it as at least a misdemeanor.”

One more of Long’s quotations made me speculate about a possible point of contact with his risen biblical namesake (beyond the obvious fact that both men lived longer than anticipated):

A human being should be able to change a diaper, plan an invasion, butcher a hog, conn a ship, design a building, write a sonnet, balance accounts, build a wall, set a bone, comfort the dying, take orders, give orders, cooperate, act alone, solve equations, analyze a new problem, pitch manure, program a computer, cook a tasty meal, fight efficiently, die gallantly. Specialization is for insects.

Long’s point (and, no doubt, Heinlein’s, too) seems to be that life is too short, even should you live for centuries, to spend it doing just one thing, or even a small handful of things. In his appreciation of the character, author Jerry L. Parker concluded, “Lazarus Long lives and strides between the stars. Supreme in the knowledge that life can end at any moment, he shouts, ‘Everything in excess! To enjoy the flavor of life, take big bites. Moderation is for monks.’”

I don’t know that Lazarus of Bethany would have encouraged immoderate living, but I do wonder if he, having been freed from his burial shroud for an unexpected second lease on life, didn’t do everything with a little more zest. After all, in the very next chapter of John, he and his sisters throw a dinner party for Jesus, where extravagance becomes the order of the evening (John 12.1-3).

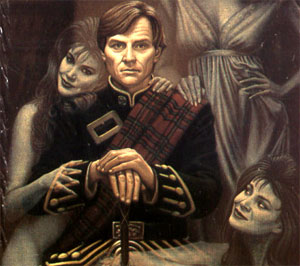

4. The Lazarus Pit (Batman comic books, video games—and films?)

Like Lazarus Long, Rā’s al Ghūl isn’t technically immortal (except, of course, to the extent that all comic book characters can escape death’s cold clutches) but extraordinarily long-lived. He has managed to wage a war of eco-terrorism for centuries “by periodically immersing himself in Lazarus Pits, pools filled with an alchemical mix of acids and poisons” that function as “a macabre fountain of youth” to sustain his “incredible vim and vigor” (The DC Comics Encyclopedia, DK Publishing, 2008; p. 283).

First introduced in 1971, Rā’s al Ghūl remains a compelling character four decades on. He appears in various Batman comic book titles (he and his family figured prominently in Grant Morrison’s latest runs involving the dark knight detective); in the much ballyhooed new Arkham City video game; and in director Christopher Nolan’s Batman Begins in which, like a more sinister version of Qui-Gon Jinn, he trains Bruce Wayne.

There are even rumors that Rā’s, along with his beguiling daughter Talia, will appear in The Dark Knight Rises next summer, further testifying to the character’s continuing appeal. (Beware potential spoilers should you choose to click through!)

What makes Rā’s such a fascinating villain? The reason could be that, like all the best bad guys of literature, he believes himself a good guy. Sure, he wants to wipe out the human race, but it’s all for the good of the planet! But, more to our point, even if we’re not supposed to root for them, we are fascinated by characters who can live forever (or very nearly so).

What makes Rā’s such a fascinating villain? The reason could be that, like all the best bad guys of literature, he believes himself a good guy. Sure, he wants to wipe out the human race, but it’s all for the good of the planet! But, more to our point, even if we’re not supposed to root for them, we are fascinated by characters who can live forever (or very nearly so).

And why shouldn’t we be? Scripture tells us we are “held in slavery by the fear of death” (Heb. 2.15). Naturally, then, we’re enthralled with the idea of overcoming death. Our only hope of doing so, however—indeed, our “sure and certain hope” of doing so, as funeral rites often state—lies not in “Lazarus pits” of our own making (not even good things like the right combinations of diet, exercise, and medicine), but in Jesus Christ. He said, “Those who eat my flesh and drink my blood have eternal life, and I will raise them up on the last day; for my flesh is true food and my blood is true drink” (John 6.54-55). For this reason, in fact, the second-century bishop Ignatius called the Eucharist “the medicine of immortality, and the antidote to prevent us from dying, but [which causes] that we should live forever in Jesus Christ” (Epistle of Ignatius to the Ephesians, chap. 20).

3. “The Lazarus Experiment” (Doctor Who, written by Stephen Greenhorn, originally aired May 5, 2007)

This episode of the revived sci-fi institution (the franchise itself has a Lazarus-like longevity, doesn’t it?) introduces us to yet another antagonist out to grab immortality, an attribute the Bible teaches us properly belongs to God alone (1 Timothy 6.16). Professor Richard Lazarus claims his new Genetic Manipulation Device will take four decades off his age. Does it? Initially, yes. But, this being Doctor Who, you know a monster has to show up sooner or later…

Professor Lazarus set out to “change what it means to be human,” but instead becomes an abomination. In his mutated, monstrous form, he boasts to the Doctor, “I’m more now than just an ordinary human.” The Doctor replies, “There’s no such thing as an ordinary human.”

That’s a lesson the rich man in Jesus’ parable, who by his self-indulgent extravagance set himself above “ordinary humans” like poor Lazarus, would have done well to learn. When we keep ourselves at arm’s length (or at creature-feature claw’s length) from our fellow mortals, we risk mutating into monsters every bit as repulsive—and as doomed and damned—as Professor Richard Lazarus.

2. Lazarus (Star Trek, “The Alternative Factor,” written by Don Ingalls, originally aired March 30, 1967)

No one I know regards “The Alternative Factor” as one of the more enduring adventures of the Starship Enterprise, but it does feature a character named Lazarus. Two of them, in fact. One hails from our “positive” universe of matter (filmed on location, as several Trek installments were, at Vasquez Rocks); the other, from a “negative” universe of antimatter (filmed on a woefully inadequate soundstage facsimile thereof). How can you tell them apart? Theoretically, because one wears a bandage on his forehead, and the other doesn’t; but this detail doesn’t remain consistent, and you can’t help but think the producers learned their lesson by the next season when they decided to give the alternate universe Spock a goatee.

I won’t attempt to summarize the plot here (braver souls have tried over at Memory Alpha). It’s a muddled affair. For years, I was convinced I didn’t understand the episode because I could only watch the sliced-and-diced for syndication version of it; however, the episode as originally aired doesn’t make any more sense. What is clear, however, is that (for whatever wacky reason) Lazarus must sacrifice himself in order to set things right. He willingly enters a trans-dimensional corridor (something that involves a fog machine, a rotating camera, and negative film exposure) to battle a raving madman for all eternity. As Lazarus asks Captain Kirk, “Is it such a large price to pay for the safety of two universes?” This Lazarus, then, resembles not so much either Lazarus from the New Testament, but, instead, their Lord and ours, who bought and saved us at great cost (1 Cor. 6.20), “to the point of death—even death on a cross” (Phil. 2.8). Like Star Trek’s Lazarus, Jesus did not shrink from self-sacrifice in order to fulfill his mission.

I won’t attempt to summarize the plot here (braver souls have tried over at Memory Alpha). It’s a muddled affair. For years, I was convinced I didn’t understand the episode because I could only watch the sliced-and-diced for syndication version of it; however, the episode as originally aired doesn’t make any more sense. What is clear, however, is that (for whatever wacky reason) Lazarus must sacrifice himself in order to set things right. He willingly enters a trans-dimensional corridor (something that involves a fog machine, a rotating camera, and negative film exposure) to battle a raving madman for all eternity. As Lazarus asks Captain Kirk, “Is it such a large price to pay for the safety of two universes?” This Lazarus, then, resembles not so much either Lazarus from the New Testament, but, instead, their Lord and ours, who bought and saved us at great cost (1 Cor. 6.20), “to the point of death—even death on a cross” (Phil. 2.8). Like Star Trek’s Lazarus, Jesus did not shrink from self-sacrifice in order to fulfill his mission.

Which brings us to…

1. Doctor Lazarus (Galaxy Quest, 1999)

I’ve never enjoyed the always enjoyable Alan Rickman as much as in this movie; not even as the Sheriff of Nottingham or as Severus Snape. His portrayal of frustrated actor Alexander Dane—who would much rather be playing Shakespeare but, for the sake of a steady paycheck, is stuck on the convention circuit portraying his sci-fi TV character “Doctor Lazarus” (Mr. Spock’s intellect with Mr. Worf’s cranium)—is only one of this film’s many riches.

But when Dane discovers that Quellek (one of the Thermians who have mistaken the “Galaxy Quest” actors for real space voyagers) has so internalized “the code of Maktar,” the noble philosophy by which Doctor Lazarus lives, that he can face his own death without fear, even the jaded thespian is moved.

I don’t know for what reason, if any, the screenwriters christened Dane’s character as they did; but Leonard Foley’s reflections (unrelated to the film) suggested a possibility:

Many people who have had a near-death experience report losing all fear of death. When Lazarus died a second time, perhaps he was without fear. He must have been sure that Jesus, the friend with whom he had shared many meals and conversations, would be waiting to raise him again. We don’t share Lazarus’ firsthand knowledge of returning from the grave. Nevertheless, we too have shared meals and conversations with Jesus, who waits to raise us, too.

Like young Quellek, who idolized Doctor Lazarus; and like Lazarus of Bethany, who died only to live again, both in this world and, eventually, the next; and even like the Lazarus of Jesus’ parable, welcomed into Father Abraham’s embrace; we, too, need have no fear of death. The apostle Paul taunts our last enemy: “Where, O death, is your victory? Where, O death, is your sting?… [T]hanks be to God, who gives us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ” (1 Cor. 15.55, 57).

By Grabthar’s hammer, may you know that same strong hope, this Saint Lazarus’ Day and every day!

Except as noted, all Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version.

Leave a Reply