I’m hoping to share a lot about Superman with my fellow sci-fi Christians in 2013—but here’s one last Bat-offering for the Dark Knight’s big year, while it’s still 2012, in the spirit of the season!

I’m hoping to share a lot about Superman with my fellow sci-fi Christians in 2013—but here’s one last Bat-offering for the Dark Knight’s big year, while it’s still 2012, in the spirit of the season!

“So Hallowed and So Gracious”

Christmas Eve enjoys a reputation, in much Western literature, as a magical night.

One of the most famous examples of this tradition occurs in the first scene of Shakespeare’s Hamlet:

Some say that ever ’gainst that season comes

Wherein our Saviour’s birth is celebrated,

The bird of dawning singeth all night long;

And then, they say, no spirit can walk abroad;

The nights are wholesome; then no planets strike,

No fairy takes, nor witch hath power to charm,

So hallowed and so gracious is the time.

I suppose it would be Grinch-like to point out that the play does, of course, begin with a ghost-sighting; I don’t know whether the Bard is thus constructing an ironic comment on this lovely piece of folklore. Either way, I still love that phrase—“so hallowed and so gracious is the time.” That Shakespeare really had a way with words, didn’t he?

A more recent example (relatively) comes from the pen of Thomas Hardy, the late-nineteenth/early-twentieth century British novelist and poet. In “The Oxen,” Hardy remembers a legend learned in childhood:

Christmas Eve, and twelve of the clock.

“Now they are all on their knees,”

An elder said as we sat in a flock

By the embers in hearthside ease.

We pictured the meek mild creatures where

They dwelt in their strawy pen,

Nor did it occur to one of us there

To doubt they were kneeling then.

So fair a fancy few would weave

In these years! Yet, I feel,

If someone said on Christmas Eve,

“Come; see the oxen kneel

“In the lonely barton by yonder coomb

Our childhood used to know,”

I should go with him in the gloom,

Hoping it might be so.

(A “barton” is a barnyard; a “coomb,” a valley.)

According to the rural elders’ traditions, oxen instinctively kneel at midnight on Christmas Eve, mirroring the way their forbears in the Bethlehem stable knelt before the Christ Child, all those centuries ago. The poet recalls this legend with sadness: he feels he has grown too old and has seen too much to put any stock in such “fair fancy.” As The Guardian explains, Hardy wrote “The Oxen” “in the midst of the carnage of the first world war… Hardy had long since lost his early religious belief–until the age of around 25 he had seriously considered a career in the church–but in the 16 lines of this poem he encapsulates beautifully the urge to faith that persists even in the face of all better judgment.” Readers sense that, any other night of the year, the poet would dismiss the legend of the oxen as ridiculous, perhaps even shameful: how could anyone tell such a tale, let alone believe it, in such a dark world? But “so hallowed and so gracious” is Christmas Eve that the poet, even if he can’t quite bring himself to believe it, at least recalls it with affectionate longing; and might even find himself setting out for that lonely barton, taking steps of faith.

Both “The Oxen” and the Christmas speech from Hamlet speak to the perceived liminal nature of Christmas Eve: a night of crossing thresholds, a span of a few hours in which the boundaries between heaven and earth blur, allowing our mundane world to be infused, however briefly, with the miraculous. And “The Silent Night of the Batman” (Batman #219, February 1970) belongs to this same tradition.

“Tonight Is Going to Be… Different!”

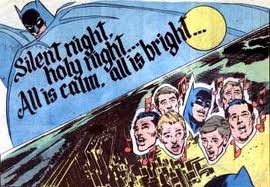

In the story, written by Mike Friedrich, Batman responds one Christmas Eve to the summons of the bat-signal only to find that Commissioner Gordon has called him in, not for an emergency, but to lend his “deep vocal chords to some Christmas carols” with some of Gotham’s finest. Batman initially objects—“Crime and disaster aren’t inclined to observe holidays!”—but Gordon insists: “Tonight is going to be… different! I know it!” Batman remains skeptical, but relents. “Why not?” he thinks. “I can enjoy myself until something happens…”

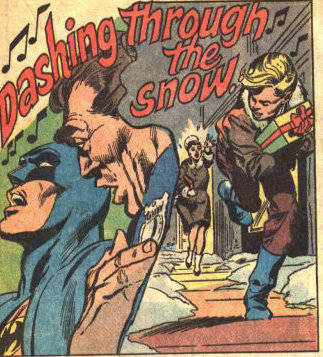

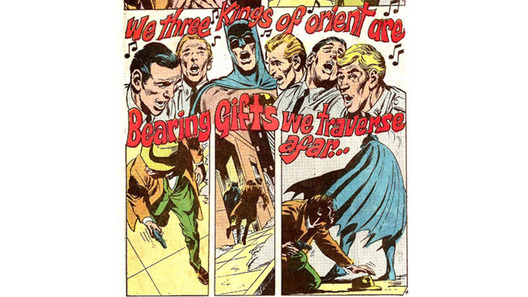

This being Gotham City, something does, in short order, happen—several somethings, in fact. Thanks to Friedrich’s story structure, the incomparable Neal Adams’ dynamic pencils, and John Costanza’s festive lettering (all with vivid ink work by Dick Giordano), three incidents form ironic counterpoints to the songs being sung back at HQ. A boy steals a woman’s wrapped Christmas parcel and runs away…

…one of Gotham’s two-bit thugs is out to commit mayhem with a handgun…

…and a young wife, despondent over her Army officer husband’s absence, makes her lonely way to a bridge–perhaps just to throw a rose over in remembrance, but perhaps to do far worse?

None of these events, however, end unhappily. When the boy and his gang unwrap the stolen gift and discover it is a Batman doll (yes, a doll—we boys of the 70s didn’t have “action figures” until Star Wars merchandising coined the term, and we turned out just fine), the would-be thief is inspired to return it. The gunman bumps into a Batman-dressed mannequin advertising a Wayne Foundation charity drive, moving him to “Keep Gotham City Clean” by throwing his pistol away. And the young wife, on spying the large, bat-like shadow of the bridge on the water, turns around to see none other than her husband leaping off an Army truck, home for the holidays after all.

Back at the impromptu police party, Batman realizes, “Good heavens!… We’ve been singing here all night! We haven’t been disturbed by one report of robbing, murder, drug-peddling… anything! It’s like the spirit of Christmas peace took hold on everyone!”

Commissioner Gordon asks, “But what is the Christmas Spirit, Batman—might it not be… you… or I?” Abruptly, “Gordon” dissolves into the air, leaving Batman to take a swing at what he decides is a hallucination. The real Gordon, however, confirms that the peace has been undisturbed all night, telling Batman: “It appears the investment you’ve put into this city has paid off tonight—giving you a night off!” As Christmas dawn breaks over Gotham City, Batman swings his way back to the Wayne Tower penthouse (no Batcave in 1970—am I right, long-time Bat-fans?), pondering Gordon’s words: “Spirit of Batman… Christmas Spirit… hmmm…”

Who is the Spirit of Christmas?

There’s something different about Christmas Eve in this Batman story, to be sure. Unlike the difference invoked in Hamlet or longed for by Hardy, however, this Christmas Even is “so hallowed and so gracious” not because of any supernatural operative, but because Batman has, as Gordon says, made an “investment” in Gotham and its people. The closing panel suggests that Batman is, in effect, the Spirit of Christmas.

Batman himself says, at the story’s outset, “Nothing ever happens just by saying it!” The story illustrates the truth of Batman’s words. He has not become a symbol capable of inspiring peace, justice, and harmony by simply wishing. He has dedicated his life to those ends. The title explains what we need to know: this “silent night” is truly “of”—belongs to; is due to the agency of—“the Batman.” He has made a real difference in at least these three lives—indeed, in the life of the entire city.

Christians believe, of course, that the reason Christmas Eve is hallowed and gracious—the reason alltime is hallowed and gracious—is because God entered time, uniquely and decisively, in Jesus Christ. “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God… And the Word became flesh and lived among us…” (John 1.1, 14). In the Incarnation, God has crossed the boundary between heaven and earth, and our mundane is f orever infused with the miraculous, solely by God’s sovereign will and loving grace.

orever infused with the miraculous, solely by God’s sovereign will and loving grace.

And yet Batman’s words still have some truth for us to hear: “Nothing ever happens just by saying it!” God has done everything, but doesn’t leave us to do nothing. We can read the Christmas story for as long and as loudly as we like, but we must also “make flesh,” in our own persons, the angelic message: “Do not be afraid; for see—I am bringing you good news of great joy for all the people: to you is born this day in the city of David a Savior, who is the Messiah, the Lord” (Luke 2.10-11). If we don’t “incarnate,” in our actions, these glad tidings—if we don’t “sing” that song with our lives as well as our lips—then others will dismiss the story as Thomas Hardy dismissed the legend of the oxen: suitable for children at bedtime, perhaps, but not for people who have seen too much to put any stock in “fair fancy.”

Maybe especially this Christmas, as our nation still mourns the victims of the Sandy Hook massacre, we know, too well, that “crime and disaster aren’t inclined to observe holidays.” Or maybe those around you, maybe even you yourself, have been touched by illness, injury, unemployment, poverty, grief—darkness takes so many forms. Our message is that God’s light shines in the darkness, and that the darkness cannot overcome it (see John 1.5)—but while the light shines in a special and unrepeatable way in Jesus Christ, God has also chosen to shine the light, reflected but nevertheless real, through us. Scripture tells us Jesus declared, “I am the light of the world” (John 8.12)—but that he also said to his followers, “You are the light of the world… Let your light shine before others, so that they may see your good works and give glory to your Father in heaven” (Matt. 5.14, 16).

We who are filled with God’s Spirit must act as the Spirit of Christmas–not only today and tomorrow, but all year, every year.

He’s known as the Dark Knight, but Batman certainly shines as a light for Gotham City. By God’s grace, may we so shine for those around us. We may or may not ever see that “investment” “pay off” in this life, as Batman saw his “dividend” of a night off on Christmas Eve, 1970—but we can know that, through us, God continues to hallow and make gracious not only this season but also this world.

Scripture quotations from the New Revised Standard Version.

For more Batman-themed Christmas reflections, you can read Mike’s 2011 review of the graphic novel Noel here.

Leave a Reply