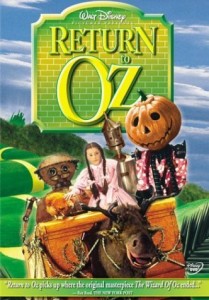

When Disney’s Oz the Great and Powerful hits theaters this weekend, it won’t be the first time the House of Mouse has taken audiences over the rainbow. Almost thirty years ago, Walt Disney Pictures released Return to Oz. Although it has, as John Grant writes in The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, fallen into “almost total obscurity” (p. 1026), it certainly doesn’t deserve to be overlooked. It is a personal and powerful, risk-taking, richly imagined fantasy that brings L. Frank Baum’s famous fairyland to the screen—its light as well as (perhaps, as we’ll discuss, especially) its shadows—far more successfully than any film ever had (or, quite likely, ever will).

When Disney’s Oz the Great and Powerful hits theaters this weekend, it won’t be the first time the House of Mouse has taken audiences over the rainbow. Almost thirty years ago, Walt Disney Pictures released Return to Oz. Although it has, as John Grant writes in The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, fallen into “almost total obscurity” (p. 1026), it certainly doesn’t deserve to be overlooked. It is a personal and powerful, risk-taking, richly imagined fantasy that brings L. Frank Baum’s famous fairyland to the screen—its light as well as (perhaps, as we’ll discuss, especially) its shadows—far more successfully than any film ever had (or, quite likely, ever will).

Goodbye, Yellow Brick Road?

Return to Oz is to some extent a sequel to The Wizard of Oz (MGM, 1939). It begins six months after the tornado that tore through Uncle Henry and Aunt Em’s farm. Dorothy has not been able to sleep through the night since because she’s convinced the friends she met over the rainbow are in peril and are calling to her for help. Aunt Em, understandably worried about her niece’s well-being and burdened by concerns over the farm’s failing fortunes, takes Dorothy into town to see Dr. Worley, an early practitioner of electric shock therapy full of turn-of-the-twentieth century faith in modernity and progress. He promises Dorothy his cutting-edge techniques can rid her mind of troubled thoughts and bad dreams about Oz forever. As Dorothy’s treatment begins, however, a violent thunderstorm erupts, knocking out the clinic’s electricity. In the subsequent darkness and chaos, another, mysterious young girl frees Dorothy, warning her of danger. The two flee to a raging river, pursued by Dr. Worley’s grim nurse, Miss Wilson. Dorothy loses consciousness—and awakens not in Kansas anymore.

The land of Oz, however, isn’t the beautiful and wondrous place Dorothy remembers. As she asks, “Where are all the Munchkins?” The Yellow Brick Road has been torn up, and it leads to an ashen-gray Emerald City, stripped of its gems, all its inhabitants, including the Tin Woodman and Cowardly Lion, turned to stone. Dorothy learns that Oz has been conquered by the subterranean Nome King. With the help of a wicked witch named Mombi—who can change heads at will, and who hopes to add Dorothy’s to her cabinet full of choices—the Nome King has “reclaimed” the jewels he feels surface-dwellers have stolen from his underground realm. Dorothy and a new band of companions—including Billina, the talking hen; the mechanical man Tik-Tok; the wooden stick-man Jack Pumpkinhead (so named for his Jack o’ Lantern noggin)— have only the slimmest of chances to free Oz from the Nome King’s stony grasp.

Excellence in Oz

Return to Oz is a superb movie. I missed it during its theatrical run, but watched every cable television airing I could. Seeing it recently for the first time as an adult, I was still impressed by how much excellent artistry is on display. Director Walter Murch (better known as an editor and sound designer) invested enormous time and energy in bringing an intricately imagined Oz to the screen, and this loving effort shines in the film’s every frame, from Mombi’s rococo palace to the Nome King’s desolate underground domain to the rubble-filled ruins of the Emerald City (spoiler alert: restored to resplendence by the end). Most of the set and character designs come straight from John R. Neill’s original illustrations of Baum’s texts, translated to the screen with remarkable skill. Although all of the special effects team deserves kudos, not-to-be-missed is Will Vinton’s Claymation, which animates the Nome King and his minions to perfection. Even in these days of CGI-saturated cinema, Vinton’s technique is mesmerizing.

Return to Oz is a superb movie. I missed it during its theatrical run, but watched every cable television airing I could. Seeing it recently for the first time as an adult, I was still impressed by how much excellent artistry is on display. Director Walter Murch (better known as an editor and sound designer) invested enormous time and energy in bringing an intricately imagined Oz to the screen, and this loving effort shines in the film’s every frame, from Mombi’s rococo palace to the Nome King’s desolate underground domain to the rubble-filled ruins of the Emerald City (spoiler alert: restored to resplendence by the end). Most of the set and character designs come straight from John R. Neill’s original illustrations of Baum’s texts, translated to the screen with remarkable skill. Although all of the special effects team deserves kudos, not-to-be-missed is Will Vinton’s Claymation, which animates the Nome King and his minions to perfection. Even in these days of CGI-saturated cinema, Vinton’s technique is mesmerizing.

The screenplay, co-authored by Murch and Gill Dennis (more recently the scribe of 2005’s Johnny Cash biopic Walk the Line), is a brilliantly conceived and executed blend of characters and incidents from Baum’s second and third Oz novels, titles, The Marvelous Land of Oz (1904) and Ozma of Oz (1907). The seamless new story actually improves upon the source material while remaining faithful to its spirit (and much of its letter).

The characters, brought to life by a talented cast, provide the movie’s heart and soul. Fairuza Balk, in her big-screen debut, delivers an understated but earnest performance, perfectly capturing not Judy Garland’s tremulous woman-child but the earnest, even-keeled, and resolute heroine of Baum’s books. The two villains of the piece are both wonderfully wicked, but never over-the-top. Jean Marsh’s Mombi strikes an entertaining medium between frightening and funny, dancing close to but never crossing the line into camp, but it’s the late Nicol Williamson who, as the voice of the Nome King (and, for a brief time, in more-or-less human form), really dominates the picture. He is by turns charming and menacing, sinister and sympathetic; above all, his ability to seed doubt in Dorothy’s mind—about herself, about her friends, about the future of Oz itself—makes him an adversary not to be underestimated.

The characters, brought to life by a talented cast, provide the movie’s heart and soul. Fairuza Balk, in her big-screen debut, delivers an understated but earnest performance, perfectly capturing not Judy Garland’s tremulous woman-child but the earnest, even-keeled, and resolute heroine of Baum’s books. The two villains of the piece are both wonderfully wicked, but never over-the-top. Jean Marsh’s Mombi strikes an entertaining medium between frightening and funny, dancing close to but never crossing the line into camp, but it’s the late Nicol Williamson who, as the voice of the Nome King (and, for a brief time, in more-or-less human form), really dominates the picture. He is by turns charming and menacing, sinister and sympathetic; above all, his ability to seed doubt in Dorothy’s mind—about herself, about her friends, about the future of Oz itself—makes him an adversary not to be underestimated.

Dorothy’s new friends really steal the show, however, realized through the masterful use of animatronics, puppetry, and good, old-fashioned practical effects. Brian Henson performs a perfectly charming Jack Pumpkinhead, giving this lanky wooden man a voice just as awkward but endearing as his physical form. And Tik-Tok, the wind-up wonder whom some literary critics regard as literature’s first robot, is a marvel, a 4-1/2 foot tall figure operated by the late dancer and trampoline artist Michael Sundin and given a voice that inspires instant loyalty and affection by Sean Barrett.

From start to finish, Return to Oz is clearly a labor of love.

Return to Which Oz?

Of course, movies that are labors of love, even major Disney movies that are labors of love, don’t always receive the recognition they deserve. (If you’re thinking John Carter, you should be—another impassioned and inspired adaptation of older American fantasy literature that Disney has all but disavowed.) Return to Oz was no box office smash, and it failed to impress critics then or many viewers now.

Two complaints frequently surface regarding Return to Oz. The first is, “There’s no music!”—by which people mean there are no song-and-dance numbers. True enough: there aren’t. While the movie boasts a beautiful score by David Shire, characters don’t spontaneously burst into melody or skip merrily down the Yellow Brick Road. I’ve been a big fan of the 1939 musical since childhood; its annual airings on CBS, long before the advent of home video or Netflix, were my first “must-see TV.” But my interest in that movie led me to read and re-read Baum’s original books, especially the two volumes from which this film draws. Its lack of musical production numbers has never bothered me, but I realize general audiences’ knowledge of Oz is limited to the 1939 film, and can appreciate why a “sequel” to it that doesn’t at least reprise “Over the Rainbow” or “We’re Off to See the Wizard” might disappoint. Even though the movie is far more about Baum’s Oz than MGM’s, Murch retained Dorothy’s ruby slippers (they’re silver in the source material) as a plot point, knowing that her famous footwear is (in Murch’s words) “part and parcel of people’s mental baggage… [and] part of the imaginative furniture of the twentieth century” (Eyles, p. 87). Unfortunately, the accommodations Murch made to MGM’s vision of Oz (including a repetition of its “double casting” stunt: Williamson and Marsh also play Dr. Worley and Nurse Wilson) may have hindered audiences from appreciating his own.

(All the same, Return to Oz isn’t completely without an instantly infectious, toe-tapping tune. Listen to the ragtime march Shire composed, and see if you don’t love it right away!)

“…Sometimes Dark and Terrible”

The second common objection isn’t as easily dealt with: “It’s too scary for the kids!” Indeed, to again quote John Grant, the film’s “real fault… was that despite appearances it is not a children’s fantasy: instead it is a fairly straightforward genre fantasy…” (p. 1026).

I admit I haven’t shown Return to Oz to my kids yet—partly because I don’t think they’d have an interest, but partly because, at least in the case of my five-year-old daughter, yes, I think she might be too scared. The “real world” set-up is unsettling, with its historically appropriate but admittedly jarring of primitive electroshock therapy for Dorothy in an asylum-like old house, complete with weeping and screaming patients locked in the cellar (never shown onscreen, but heard on occasion). This semi-Gothic setting doesn’t overly creep me out, and never has, but as an adult, I do find it scary to realize that adults who are trying to help the children they love as best they can, as Aunt Em surely is, sometimes run the risk of exposing them to greater harm. Of course, most doctors and nurses aren’t like Dr. Worley and Nurse Wilson; but I could imagine a young child might dread an upcoming doctor’s visit even more after seeing this movie!

And, for all that Baum himself wrote, in his first Oz story, that it is “a country that is sometimes pleasant and sometimes dark and terrible,” I have to concede the 1939 film balances the two sides of that equation better than Return to Oz does. The Wizard of Oz has several scary moments—it’s not for nothing that Margaret Hamilton had to reassure young viewers of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood that she just playing make-believe—but most viewers come away with the overriding impression that Dorothy’s Technicolor destination over the rainbow is a terrific place.

But although Dorothy’s return trip to Oz in this film ends with some scenes of celebration and joy, those emotions are definitely muted. Children (not to mention adults) who adore “the merry old land of Oz” in the former film may not enjoy seeing it reduced to a shadowy shambles in the latter. This is not to say there is no humor or warmth in the rest of the film—Tik-Tok and Jack Pumpkinhead make a wonderful comedic duo, for example, and the poor, mounted head of the Gump (apparently Oz’s version of a moose) who finds himself attached to a sofa with palm-leave wings offers comic relief—but there’s simply no denying Return to Oz is a more somber work.

But although Dorothy’s return trip to Oz in this film ends with some scenes of celebration and joy, those emotions are definitely muted. Children (not to mention adults) who adore “the merry old land of Oz” in the former film may not enjoy seeing it reduced to a shadowy shambles in the latter. This is not to say there is no humor or warmth in the rest of the film—Tik-Tok and Jack Pumpkinhead make a wonderful comedic duo, for example, and the poor, mounted head of the Gump (apparently Oz’s version of a moose) who finds himself attached to a sofa with palm-leave wings offers comic relief—but there’s simply no denying Return to Oz is a more somber work.

Having granted that fact, however, I would submit that its solemnity makes it a far more rewarding work, as well—and if I thought my eleven-year-old son were at all interested, I’d have no hesitation showing the movie to him, or to most kids in the middle grades or older. I was 13 when Return to Oz was released, meaning I was just entering that “sometimes pleasant and sometimes dark and terrible” country known as adolescence. Although I don’t think I could have explained why at the time, looking back, I think this movie appealed to me because it took some stories I loved as a child and made them feel like they still somehow mattered.

Some real and important things are at stake in Return to Oz, not the least of which is that fairyland’s very future, and Dorothy’s continued loyalty to it. Composer David Shire has explained, “The subtext of the movie, according to Walter [Murch], is that Dorothy is going back to Oz to… somehow find a way to be true to the world of her imagination while living in the real world.” While I think the film is moderately more ambiguous on the question of Oz’s “reality” than is the MGM film (in Baum’s books, Dorothy and her family eventually go to live in the Emerald City), this reading of the movie makes a lot of sense to me, and I suspect, as a youth who often preferred my imagination to reality, I may have intuited some of it during all those viewings.

I also can’t help but wonder, being a sci-fi Christian, if God doesn’t also have something to do with this film. If you’re looking for explicitly Christian messages in it, you won’t find them; but neither will you find anything opposed to faith (unless you are that kind of Christian who opposes The Wizard of Oz on a “no stories about witches and wizards” principle, in which case you’re not likely to have read this far). In fact, you might find a glimmer, in Dorothy’s journey between worlds, of believers’ own lives as “dual citizens.” “Our citizenshipis in heaven,” writes the apostle Paul (Phil. 3.20)—and while we must live in this world, we are not (or ought not to live as though we are) of it. As Dorothy does by this movie’s end, we always have access to another land—“a better country… a heavenly one” (Heb. 11.16)—where we are at home, and where lives a gracious Sovereign who watches over us in love, who will one day bring us back.

I also can’t help but wonder, being a sci-fi Christian, if God doesn’t also have something to do with this film. If you’re looking for explicitly Christian messages in it, you won’t find them; but neither will you find anything opposed to faith (unless you are that kind of Christian who opposes The Wizard of Oz on a “no stories about witches and wizards” principle, in which case you’re not likely to have read this far). In fact, you might find a glimmer, in Dorothy’s journey between worlds, of believers’ own lives as “dual citizens.” “Our citizenshipis in heaven,” writes the apostle Paul (Phil. 3.20)—and while we must live in this world, we are not (or ought not to live as though we are) of it. As Dorothy does by this movie’s end, we always have access to another land—“a better country… a heavenly one” (Heb. 11.16)—where we are at home, and where lives a gracious Sovereign who watches over us in love, who will one day bring us back.

Return to Oz may not be appropriate for very little children, but it will speak to the child inside you. If you’ve never heard of it, or have been put off by its lackluster (undeservedly so) reputation, I encourage you to give this beautiful, ambitious, and sensitive film a chance to work its magic on you.

Scripture quotations from the New Revised Standard Version.

Works Cited:

John Clute & John Grant. The Encylopedia of Fantasy. 1997. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 1999.

Allen Eyles. The World of Oz: A Fantastic Expedition Over the Rainbow. Tucson, Arizona: HPBooks, 1985.

Electroshock!

I am ashamed to say I have never seen this one, but I want to!

Daniel – I am shocked, too! You the Disney expert! It’s good – see it asap!

This shows my viewing habits. I guess I could rent on Amazon…..but I don’t like to watch movies on computers!

You should be able to pick up a DVD on Amazon or eBay.