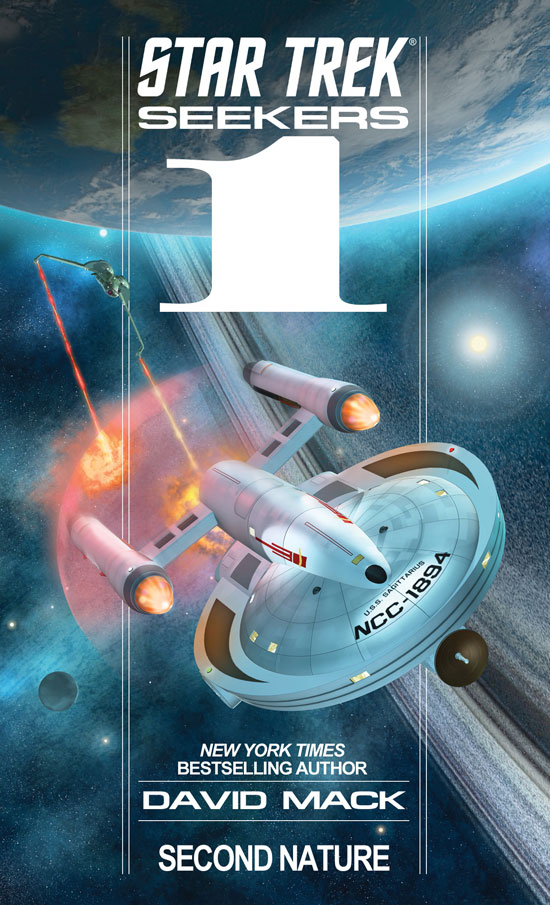

Despite the cautionary proverb about books and their covers, I not only judged but promised myself I’d buy David Mack’s Second Nature, the first entry in Pocket Books’ new Star Trek: Seekers series, as soon as I saw its cover art.

Despite the cautionary proverb about books and their covers, I not only judged but promised myself I’d buy David Mack’s Second Nature, the first entry in Pocket Books’ new Star Trek: Seekers series, as soon as I saw its cover art.

It wasn’t just the dramatic image that sold me, though there’s no doubt artist Rob Caswell knows how to paint an attention-grabbing scene. The overall design intrigued me. Those vertical lines, that fat Arabic numeral front and center—it all deliberately evokes the covers of James Blish’s 1970s novelizations of Star Trek’s original episodes.

In 1984, as a newly minted Trek fan, I checked those paperbacks out of my middle school’s library and pored over them, often reading any given story long before I’d see the actual episode on which it was based. The Blish books fueled my early fandom and energized my imagination.

So when I read that Seekers would relate new voyages of a new starship with a new crew, set in the familiar Original Series time frame, I got excited. If Second Nature could launch a line of books that made me feel, as I did thirty years ago, that the Star Trek universe was fresh and vast and weird and wonderful, it would make me one very happy fan.

Did Second Nature make me feel like a 14-year-old Trekkie again?

Of course not. No book could. But it’s not a bad book. In fact, it’s quite good.

The plot revolves around the Tomol, aliens who undergo radical metamorphoses as they mature into young adults. We’re not talking normal adolescence; we’re talking uncontrollable psychic energy and physical power that could turn the Tomol into god-like entities. I say “could” because the Tomol, rather than see “the Change” through, submit to “the Cleansing.” In keeping with the scriptures of their ancient Shepherds, they burn themselves alive in a fiery pit rather than become a danger to others. But when one young woman, Nimur, rebels and embraces her new powers, she sparks a cataclysmic disruption to the Tomol’s status quo, a societal shift that sweeps up not only a covert Klingon military research mission—headed by familiar foe Kang (from “Day of the Dove”)—but also our Starfleet protagonists.

I’m unclear whether fans who’ve stuck with Pocket’s Trek lines in recent years already know the crew of the scout ship Sagittarius. Mack largely neglects character development, leading me to suspect he did the hard work of characterization in previous Trek titles (events from which he explicitly references in Second Nature). It’s not his fault I haven’t read them.

My ignorance, however, did leave me feeling that Seekers’ promise of a “new crew” is only true from a certain point of view (as that other famous “Star” franchise puts it). Aside from the Sagittarius’ commander, Captain Clark Terrell (who will meet his untimely demise in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan), none of the Starfleet crew feel like fully realized individuals. They emerge as close analogues of classic characters (e.g., the Arkenite science officer, Hesh, is super smart but befuddled by emotions, a lot like Spock of old) or walking character traits (e.g., Faro Dastin, a Trill officer, is impulsive and likes to crack jokes). If Second Nature is less of a “square one” than a “jumping-on point,” it fails to make this jumper, at least, care too much about them.

I sense Mack wants this crew to seem more like real people than the paragons of professionalism who populated the Enterprise in the Original Series. But hearing Starfleet personnel swear as casually as these folk do doesn’t ring true, and I’d like to think such modern colloquialisms as “not cool” and “puking” and “save our asses” will have disappeared from the Federation’s vernacular. Original Series-era Trek characters don’t talk this way, and I’d prefer Mack find other, more creative ways of making his crew relatable.

In their favor, the Sagittarius crew is more diverse than the on-screen crew of Kirk’s Enterprise. And while I don’t feel I know them (again, apart from Captain Terrell; Mack perfectly captures Paul Winfield’s performance in print), I like them and am willing to read more about them—fortunately for Pocket, since Second Nature ends on a cliffhanger.

I wonder whether the next book, due late this month, will delve into the religious issues raised by this one. Nimur sees herself as a prophetic liberator of the Tomol, destined to free them from the shackles of traditional doctrine and practice that they might undergo an apotheosis like hers. What actually happens, of course, is that Nimur prematurely “awakens” other Tomol who then serve as her minions (or “myrmidons”—thanks to Mack for expanding my vocabulary). Such a dynamic is too familiar to students of world religions: recipients of revelation take it upon themselves to become oppressive revealers. Certainly, Christians can point to and should still repent of times when Jesus’ people have forced their vision and will on others, falsely claiming it to be his. Can Nimur be saved from that fate, or has she irrevocably committed herself to a tragic end?

All in all, Mack turns in a clearly written, crisply plotted, entertaining read. It’s light on the philosophical and moral musings integral to Star Trek’s DNA, and it doesn’t quite live up to its magnificent cover’s promise of making the Trek universe feel wide-open once more—but it does deliver a few hundred pages of fun, fast-paced space opera. Here’s hoping Seekers builds on that strength in coming installments.

All in all, Mack turns in a clearly written, crisply plotted, entertaining read. It’s light on the philosophical and moral musings integral to Star Trek’s DNA, and it doesn’t quite live up to its magnificent cover’s promise of making the Trek universe feel wide-open once more—but it does deliver a few hundred pages of fun, fast-paced space opera. Here’s hoping Seekers builds on that strength in coming installments.

After all, book 2 is sporting an even better cover!

Leave a Reply