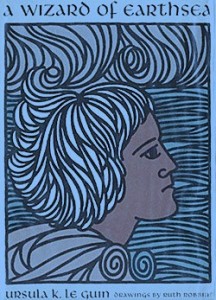

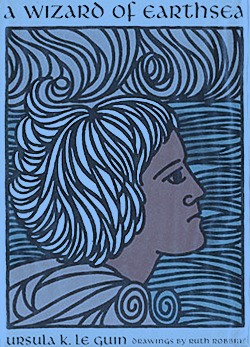

*Spoiler Alert* This week we discuss chapters 1, 2, and 3 of Ursula K. Le Guin’s A Wizard of Earthsea.

*Spoiler Alert* This week we discuss chapters 1, 2, and 3 of Ursula K. Le Guin’s A Wizard of Earthsea.

These first chapters outline Ged’s early life and progress into the magical arts, from his accidental enchantment of goats to his time at the Wizzarding school at Roke. While he grows in power, his yearning for mastery never ceases, transforming into hubris and jealousy towards his self-made rival, Jasper. Perhaps this is the very thing that Ogion was attempting to prevent from happening; he tries to teach Ged patience and humility. Those, we all know, are the most difficult lessons for a young person to learn.

The themes in these first few chapters resonate with works throughout fiction, and my mind conjured images of Star Wars, or at least, what the prequels could have been. Here we have a promising, powerful adept who is not initially arrogant but wild and in need of true guidance. His first teacher does her best, but only serves to increase his desire for power. His second moves far too slowly, and it is only when he is put in control of his own destiny is Ged satisfied with his growth…save for the presence of Jasper, who he feels he must outperform. Ged knows his strength, and yearns to tap into it; it is not a stretch to imagine him overreaching his control and performing a grave error.

Another interesting concept Le Guin develops is the concept of “true names.” I understand that these names come from the ancient language of Earthsea, but what fascinates me is where these names come from. Who gave the hawks and the trees their true names? How does Ged get his name? The author tells us Ogion gives it to him, but where does the Mage get it from? I trust that the true name must be unique, for it is language that is the power of magic in this world, so it cannot be like picking a regular name for a child.

If Ogion made one up on the spot, like Ralphonzo, might there be another Ralphonzo in Earthsea? If a true name can control, would it control both Ralphonzos? I believe Le Guin envisions an individual name for each person in Earthsea; Unlike the hawk, who has a name for the species as a whole, each human receives a true name, requiring uniqueness. If this is the case, they must come from an external source, not simply the mage who has given it. In this way, I feel A Wizard of Earthsea can provide excellent opportunities to look at Christianity and language, and how they are interconnected.

Please comment below, and we can discuss this work as a community. If you have read ahead (as I was sorely tempted to do) please leave any spoilers for later chapters until the week they will be discussed. Tell me what you thought of the book, what ideas it brought forth, or just comment on what I have said already. Also, if the length of reading was too much, please let me know…it was not a problem for me, but I definitely don’t want this to be a stressful experience!

Thank you for joining me, and I look forward to your fellowship!

as i understand it, the true names of things are the names in the language of The Making (creation) that has been long forgotten by all but the wizards, and then they still devote their lives to learn only a handful of the words. there is a person that is given credit to The Making and the formation of the isles of Earthsea, but i forgot his name. 🙁 God i love this book!!

I am enjoying the character of Ogion. He and Ged have a very Yoda-Luke (and also very Zen Buddhist) master-pupil relationship — “But I haven’t learned anythnig yet!” “Because you haven’t found out what I am teaching.”

I agree that a person or thing’s “true name” has to be discovered, not manufactured. It comes from outside ourselves. As far as a connection to Christianity, it makes me think of that verse from Revelation: “To everyone who conquers… I will give a white stone, and on the white stone is written a new name that no one knows except the one who receives it” (2.17, NRSV). The moment where Ged hesitates before revealing his name at the school threshold — “for a man never speaks his own name aloud, until more than his life’s safety is at stake” — is a nice one (and proves important later on), establishing the almost sacred nature of this “true name” in Earthsea.

Thanks for getting the ball rolling, Joshua — looking forward to more!

While reading the first chapter, I kept thinking of YHWH, and how in the Jewish tradition, the name of God is not to be said; also, that the name YWHW is still somewhat of a mystery. Can we truly know God without knowing His name? Is that even important? Knowing that his name means “I am that I am,” and that it is the name He has chosen for Himself, it would seem important to understanding how He views Himself.

Yes — as I understand it, God’s name is YHWH because it is not a name that can be completely encompassed. It’s a name in flux… To speak of YHWH is to speak of One who is/will be what that One is/will be. Unlike other names, the name YHWH points to rather than proscribes the freedom of the name-bearer.

If memory serves, this turns out to be different from the power of names in Earthsea, which is the very traditional idea that when you know a thing’s true name, you have power over it. I think there’s some scholarly work on the idea that Moses, knowing he was going to go up against Egyptian magicians, wanted power over God in the way the Egyptians invoked their deities; therefore, God was having a little fun at Moses’ expense when giving this slippery name.

A thought about magic in Earthsea occurred to me as I read today, sparked by a fleeting comparison to the “Harry Potter” series — both tales involving schools for wizards, after all. Does it seem like magic is much more of a powerful force (but not, perhaps of nature?) in Earthsea, to be used only sparingly and responsibly?

This is the passage — from early in Chapter 4, so I’m only a little bit ahead! — that made me think this: “The weatherworker’s and seamaster’s calling upon wind and water were crafts already known to his pupils, but it was he who showed them why the true wizard uses such spells only at need, since to summon up such earthly forces is to change the earth of which they are a part.”

Off hand, I can’t think of anyone in Harry Potter who uses magic sparingly, and with concern for its unintended repercussions. Even such simple things as washing the dishes, at least in the Weasley household, get done by magical means.

Any great significance to be found in this, or is it simply a function of Harry Potter being (it seems) more self-consciously children’s literature (though not just that) than Earthsea?

I seem to remember J.K.R. stating that she had no intended audience for the HP series, and it was the publishers who decided to market them towards kids…whether that says anything about her writing ability is another story.

That being said, I recall Ogion (as well as the narrator) mentioning the balance quite often in reference to magic usage, and I think we’ll get a notion of the repercussions in later chapters. I think in Earthsea, magic is a product of the natural world, an extension of creation, if you will. In HP, it’s just there; it’s a tool that some can use and others cannot, and like most tools it can be used for good, benign, or evil actions. It’s a very shallow interpretation in relation to Earthsea’s take on it.

It could be that, in Earthsea, Magic does not create so much as it manipulates. In one section (this may be from 4/5) it is explained that making it rain in one city causes drought in another; rain is not created but moved from one place to the next. In the HP world, things are actually created by magic. If nothing is taken from somewhere else, there should be few consequences from that action apart from the immediate.

Thank you for your comments, Michael! Keep them coming!