I admit: Real Steel was not on my movie-going radar. “A movie based on ‘Rock ‘em, Sock ‘em Robots?’” I thought. “What’s next, a movie based on ‘Battleship?’” (Little did I know…)

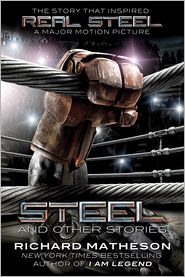

As it turns out, of course, the new Hugh Jackman pic is based, not on a toy, but on a short story by acclaimed science fiction and horror author Richard Matheson. I wasn’t aware of this fact until the Sci-Fi Christian’s own Ben de Bono mentioned it on this week’s podcast. Matheson’s story even made it to the screen (the small one) once before, as an episode of The Twilight Zone.

Real Steel opened in the top spot at last weekend’s box office; its $27.3 million haul even set a new record for the biggest debut of a boxing film ever. (Take that, Italian Stallion!) Whether the film’s fancy footwork will outclass that of the remade Footloose this weekend is yet to be seen. (UPDATE: Real Steel did just fine, thank you very much, winning its second consecutive weekend–that seems an increasingly tough feat for films these days!)

On the strength of its pedigree, I decided I want to see this movie. Before I do, however, I took a look at both Matheson’s story and its Twilight Zone adaptation. Given what I found, I’m intrigued to learn that Real Steel already has a sequel in the works, because both previous versions of the source material don’t seem to lead to anything but a dead end.

Note: Spoilers for both the story and the television episode follow.

The Story: “Steel” (first published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, May 1956)

“Steel” is a heartbreaking story. Tim Kelly is a former prizefighter. He never amounted to much in the ring but still prides himself on his nickname: “Called me ‘Steel’ cause I never got knocked down once. Not once.” Age and time, however, now threaten to KO Kelly: he’s well past his physical prime (he spends much of the story sweating), and his sport has been outlawed, at least as he knew it. Human boxers have been replaced by robotic ones.

“Steel” is a heartbreaking story. Tim Kelly is a former prizefighter. He never amounted to much in the ring but still prides himself on his nickname: “Called me ‘Steel’ cause I never got knocked down once. Not once.” Age and time, however, now threaten to KO Kelly: he’s well past his physical prime (he spends much of the story sweating), and his sport has been outlawed, at least as he knew it. Human boxers have been replaced by robotic ones.

Kelly tried to adapt. He bought an android called Battling Maxo. Like its owner, Maxo reached the threshold of success but never managed to cross it. Increasingly advanced models of robots superseded Maxo long ago, but Kelly remains proud of it. For the last twelve years, he’s been eking out a threadbare existence hauling Maxo to the few backwater bouts that will take him, confident that the next fight will be the purse that pays the bills and changes everything. “We’ll be loaded after the fight,” Kelly promises Maxo’s mechanic, Pole; “I’ll buy you a steak three inches thick.”

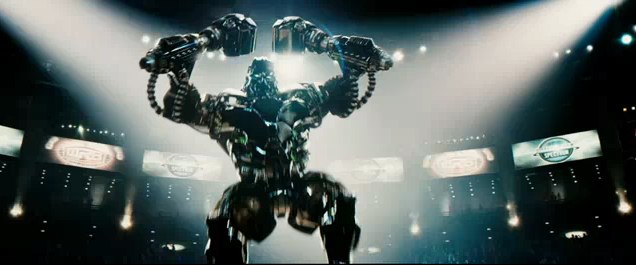

When Maxo irreparably breaks just before a bout in Maynard, Kansas, however, a desperate Kelly feels he has no choice but to impersonate his machine and fight in its place: “If we don’t deliver a fight we don’t get paid… Nobody knows what Maxo looks like… The [boxing robots] bleed and bruise too.” Kelly enters the ring and barely goes one round against the Maynard Flash, a cutting-edge android. The story ends with Kelly—bloodied and broken, and paid only half of what he was promised due to the bout’s brevity—still dreaming of Maxo’s comeback: “he struggled up on his left elbow and turned his head, pain crackling along his neck muscles. When he saw that Maxo was all right he put his head down again. A smile twisted up one corner of his lips.”

No steak dinner.

When Kelly looks at Maxo, he sees a survivor like himself. He tells Pole that Maxo’s “been doin’ okay for twelve years now, and he’ll keep on doin’ okay. So he needs some oil paste. And he needs a little work. So what?” When we readers look at Maxo, however, we see a machine that simply can’t keep taking the poundings life is doling out—and neither can Kelly. Pole warns him, “You’re up against a machine!,” and we sense he’s talking about more than this specific match. Kelly is up against not just a machine, but the “machine,” the system of a society obsessed with the strongest, the fastest, the newest. Everything else is dismissed with the “inevitable” cry of “Scrap iron!” It’s seen as nothing more than refuse, worth only the fact that it can be consumed as raw material for making more of what it replaced. Early in the story, Pole describes the next model of fighting robot due to come off the assembly line: “Hyper-triggers in both arms—and legs. All steeled aluminum. Triple gyro. Triple-twisted wiring. God, they’ll be beautiful.” His casual invocation of God’s name is telling. This is a society seeking beauty and transcendence, even salvation, in its technology.

We readers cannot help but sympathize with Kelly—the story’s climactic scene delivers an emotional impact to nearly as devastating as the physical blows he suffers—but we might also pause to remember that he accepts his society’s values even in the way he defies them. His tenacious but obviously misplaced faith in Maxo validates his society’s invalidation of him. Even while he is putting up his futile fight against the Maynard Flash, he sees it as “the tall beautiful figure in front of him.” It is called, in fact, “an impassive Adonis.” The name of the ancient Greek god is especially appropriate, beyond its common usage as a byword for physical excellence; Adonis was capable of endless deaths and resurrections, just as this society’s boxing androids are endlessly “resurrected” in new models, supplanting the old ones. Who can go up against such a god and win? No human, as Kelly seems to instinctively realize. He only summons the stamina to stay on his feet for as long as he does by chanting to himself the mantra, “I’m a robot… a robot.” I don’t mean to judge Kelly harshly, but he is complicit in his own dehumanization. He is sacrificing his humanity to the machines his society worships.

The Episode: “Steel” (first broadcast October 4, 1963; written by Richard Matheson; directed by Don Weis)

Matheson translated his story to the small screen with extreme faithfulness. Lee Marvin (four years prior to The Dirty Dozen) turns in a strong performance as Kelly, capturing both the character’s confidence and determination. Joe Mantell (who would, a decade later, speak the final and most famous line in Chinatown; and who had already appeared on The Twilight Zone in the second season’s “Nervous Man in a Four-Dollar Room”) is adequate as Pole; the script, out of necessary time constraints, doesn’t give him much to work with.

Matheson translated his story to the small screen with extreme faithfulness. Lee Marvin (four years prior to The Dirty Dozen) turns in a strong performance as Kelly, capturing both the character’s confidence and determination. Joe Mantell (who would, a decade later, speak the final and most famous line in Chinatown; and who had already appeared on The Twilight Zone in the second season’s “Nervous Man in a Four-Dollar Room”) is adequate as Pole; the script, out of necessary time constraints, doesn’t give him much to work with.

Another casualty of the transition from page to screen is the fight itself. The arena atmosphere is very well realized, through judicious use of smoke and well-placed reaction shots from members of the crowd; and Chuck Hicks is convincing as the Maynard Flash, thanks not only to his own physical presence but also to makeup artist William Tuttle’s striking prosthetics (applied with equal success earlier in the episode to Tipp McClure as Maxo). While all the action happens just as it does in the story, however, viewers simply can’t have the immediate access to Kelly’s thoughts and emotions that readers do.

The episode’s sole serious misstep comes with Rod Serling’s framing narrations. In his opening comments, Serling, after mentioning the abolition of prizefighting, says Kelly and Pole will learn “that no law can be passed which will abolish cruelty or desperate need—nor, for that matter, blind animal courage.” Likewise, in his closing comments, our host suggests that we’ve just witnessed “proof positive” not only “that you can’t outpunch machinery”—a conclusion fully warranted by Matheson’s story—but also “that no matter what the future brings, man’s capacity to rise to the occasion will remain unaltered. His potential for tenacity and optimism continues, as always, to outfight, outpoint, and outlive any and all changes made by his society, for which three cheers and a unanimous decision rendered from the Twilight Zone.”

Serling’s upbeat gloss on “Steel” feels forced. Tom Kelly is tenacious, no doubt about it; but he is more willfully blind to the truth than optimistic (although I suppose all optimists leave themselves open to that charge). His continued devotion to Battling Maxo, his ongoing willingness to spend himself in the service of his hopelessly obsolete machine, is slowly but surely killing him. Even as televised, his final speech to Pole, in which he anticipates Maxo’s future, has the air of the Pietà about it: Kelly, sprawled and bleeding on the ground, while Pole bends over him, tending to his wounds. The man they called “Steel” because he was never knocked down, “not once,” is out for the count. Machine has done what man could not—just as, ostensibly, man says he has created machine to do. Serling tries valiantly to paint Matheson’s story as a parable of optimism and the indomitable human spirit, but it simply isn’t. As author Marc Scott Zicree writes in The Twilight Zone Companion, “Rather than seeming an act of courage, on the face of it Steel’s actions seem the result of a near-suicidal bullheadedness.”

“Is Not This Thing a Fraud?”

Does the society of “Steel” sound like any societies you know?

I think about those impromptu shrines people put up outside Apple stores worldwide following Steve Jobs’ death. I remember the furor surrounding the first release of the iPhone: anticipation was so great, many dubbed it “the Jesus Phone.” Even as I write this morning, die-hard devotees are lining up outside the Philadelphia Apple store in order to be among the first to greet the iPhone’s latest incarnation.

I think about those impromptu shrines people put up outside Apple stores worldwide following Steve Jobs’ death. I remember the furor surrounding the first release of the iPhone: anticipation was so great, many dubbed it “the Jesus Phone.” Even as I write this morning, die-hard devotees are lining up outside the Philadelphia Apple store in order to be among the first to greet the iPhone’s latest incarnation.

I agree that Jobs was a visionary whose impact on our society and culture cannot be overestimated. And I love gadgets, too (when they’re working properly). But do we elevate technology too highly and trust in it too much?

We wouldn’t be the first. The prophet Isaiah mercilessly mocked those too enamored of their applied sciences. Look at the foolish woodman, he chortles, chopping down a tree and burning half of it for warmth, only to carve an idol from the other half: he “bows down to it and worships it; he prays to it and says, ‘Save me, for you are my god!’… He feeds on ashes; a deluded mind has led him astray, and he cannot save himself or say, ‘Is not this thing in my right hand a fraud?’” (see Isa. 44.9-20).

Kelly ostensibly wants to save and redeem Battling Maxo—but isn’t he really looking for Maxo to save and redeem him? Technology can be good. God has given us minds with which to discover and develop and dream new technological possibilities. But when we forget technology’s proper place and set it up as a god, we, like Kelly, are also setting ourselves up for a colossal knock-out.

All Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version.

I don’t think I have read this story, but I really like Matheson’s work. It makes me want to see the movie.

Me too, Budd. The only other work of Matheson’s I’ve read is “I am Legend,” which I also enjoyed. (Liked the Will Smith movie, too, though I think I am in the minority on that.) I’ve also, of course, seen many (but, clearly, not all) of his “Twilight Zone” episodes.

Fun fact: this episode aired the week before “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet,” also by Matheson!

Thanks for reading and chiming in, as ever!

Thanks for the thoughts Mike, I also had relegated this movie to the dustbin of my mind. Had no idea Matheson lay at its origins. I’ve always liked him and he has quite a range the movies Somewhere in Time and The Legend of Hell House are both based on his works. Your comments about Serlings framing narration were interesting and I suspect he closely identified with the main character in “Steel”. You are right it can seem jarring but it does fit with the character of the man, and I believe that character is a large part why people still love to watch the old episodes. So I can forgive Serling for wishing to redeem Kelley.

Finally I wanted to give you a thanks this post put my behind in gear and had me crank out a new segment for the “Twilight Zone” script I’ve been working on forever.

Rick

No arguments with you about Serling’s appeal, Rick! I hadn’t stopped to consider that Serling personally might have identified with Kelly but, knowing what little I do of his life, it certainly sounds plausible.

I’d love to hear more about that “Twilight Zone” script as you can share! Thanks again for the insightful comment.

Watched Twilight Zone’s “Steel” on Netflix this weekend. Not bad, I don’t think the movie will have that much in common…it’s not the best episode, but I really liked Lee Marvin’s performance. His obsession with an obsolete piece of machinery, echoing his own failings as a boxer, really came through.

Yes, Joshua — Kelly’s self-identification with Maxo is really heartbreaking, especially on the page. To be sure, it’s not the TZ’s strongest episode (it’s also one of those few that lack the signature “twist ending” — it might have been more at home on the old “Outer Limits”), but, like you, I think Marvin’s work holds up.