That’s the question the Doctor and Susan ask about the TARDIS when they realize that, despite its appearance in a Stone Age setting, the time machine still looks like a 1960s public police call box! But, it’s a question that applies equally well to Doctor Who as a whole.

In almost 50 years, why hasn’t it changed?

Of course, it has changed in some ways over the decades. Look no further than the procession of actors playing the title role! The show’s basic formula, however, is firmly in place in this first story.

- We have that wonderful police box that’s bigger on the inside. The moment Ian puts his hand on its side and, in awe, calls it “alive,” I couldn’t help but think of Suranne Jones’ entrancing performance in “The Doctor’s Wife.” I don’t really think the show’s creators were consciously planting seeds for Neil Gaiman to harvest 48 years later; at the same time, it’s not too hard to trace a direct trajectory from the junkyard at 76 Totter’s Lane to the “junk planet” where the TARDIS took on human form.

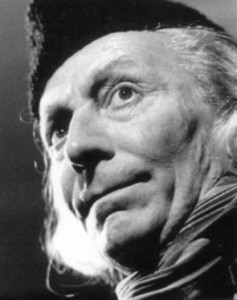

- We meet the solitary time traveler himself. He’s not yet “the last of the Time Lords,” nor yet even identified as a Time Lord. He tells us only that he and his granddaughter “are cut off from our own planet, without friends or protection. But one day we shall get back. Yes, one day. One day” (the current Doctor, Matt Smith, echoed this line in “The Almost People”). Since Susan is with him, the Doctor is not technically traveling alone—but, for most of the story, he’s set apart physically and, especially, emotionally. He is a consummate enigma—even, perhaps, to himself. When William Hartnell became the first actor to speak the show’s title on screen—“Doctor who?”—he wasn’t setting up the revelation in “The Wedding of River Song” that this is “the first question, the question that must never be answered, hidden in plain sight; the question you’ve been running from all your life!” But he was creating a mysterious character whose depths his ten successors have plumbed, to varying degrees. The Doctor is, and will continue to be, irascible, unpredictable, and irresistible.

- We relate to the Doctor through temporarily temporally displaced “companions.” I am completely taken with the character of Susan, who defers to the grandfather she dearly adores but isn’t afraid to stand up to her teachers, correcting both them and their textbooks on the basis of her firsthand knowledge of the past. I also enjoyed Ian: it’s clear to see that he, not the Doctor, was intended to be the “hero” of the program. (Ah, producers’ best-laid plans!) I liked Barbara for the first half-hour of the story, but then her misadventures with the Clan of the Cave Bear turned her into a helpless screamer (as I understand it, a staple of the classic series—another element of the format locked into place!).

- And, of course, we materialize in the midst of a situation in search of a solution. Were this story “tweaked” just a bit (no disparaging remarks about the “savage mind” of the “Red Indian,” for instance; and, again, less screaming from Barbara), “An Unearthly Child” would make a sold Doctor Who adventure today.

The show’s flexible but recognizable format really hasn’t changed. Granted, today’s Doctor would take a more active role in the goings-on. No doubt he would kindle the fire, not Chesterton; but Chesterton would still be his foil, and it’s not too hard to imagine a modern Doctor (especially Eccleston) tossing off the same critiques of humanity. We’ve seen plenty of modern Who tales take us humans to task for fearing what we don’t understand (e.g., “Midnight,” “Cold Blood”).

The show’s flexible but recognizable format really hasn’t changed. Granted, today’s Doctor would take a more active role in the goings-on. No doubt he would kindle the fire, not Chesterton; but Chesterton would still be his foil, and it’s not too hard to imagine a modern Doctor (especially Eccleston) tossing off the same critiques of humanity. We’ve seen plenty of modern Who tales take us humans to task for fearing what we don’t understand (e.g., “Midnight,” “Cold Blood”).

I don’t think the Doctor would abscond with unwilling companions any more, nor would he worry about becoming the subject of “idle gossip” (the unaired pilot had a more convincing motivation for the Doctor’s decision to take Ian and Barbara with him: he felt himself bound by a kind of “temporal prime directive,” and Susan’s teachers simply knew too much). But, certainly Tennant (and no doubt others I haven’t yet met) would also have enjoyed taking Chesterton down a few pegs!

Still, for all his relative inactivity, Hartnell creates a compelling character. When he describes the “concrete proof” Chesterton seeks—“If you could touch the alien sand and hear the cries of strange birds and watch them wheel in another sky, would that satisfy you?”—he anticipates any number of times the Doctor will extol the wonders of traveling in time and space (for example, this speech in “Night Terrors”: “Through crimson stars and silent stars and tumbling nebulas like oceans set on fire; through empires of glass and civilizations of pure thought, and a whole terrible wonderful universe of impossibilities…”).

And today’s Doctor would at least try to leave Za’s tribe better off than he found it. (His plan probably wouldn’t involve trying to kill Za with a rock—yikes!) The “solution” to this story’s central conflict was its least satisfying element: not because it is unrealistic, but because it is unrelentingly grim. Za, Hur, Kal and the rest are never explicitly established as “humans,”—fans debate whether this story is even set on Earth—but they clearly represent primitive humanity. I wonder whether the Doctor would allow any significant difference between these shivering cave folk and modern human beings. Chesterton speaks noble words about how, in his “tribe,” the firemaker is the least important because “everyone can make fire.” Even the Doctor teaches Za that “Kal is not stronger than the whole tribe.” But that kind of truly egalitarian community remains elusive, doesn’t it? We still honor our “firemakers”—and we still turn on them when they let us down. We still act as though our “Kals”—our bullies, intent on lording it over us—are stronger than the community (though sometimes we remember—witness the “Arab spring”). I felt sorry for Za (even though I wondered how it was his father never got around to teaching him to kindle fire, especially when survival on their world is so precarious). Za did show compassion to Kal, and Kal certainly didn’t repay that kindness. But it’s a shame Chesterton’s gift of fire only served to fulfill the Old Woman’s prophecy: “Fire will kill us all in the end.” (It’s not hard to find fears of the early atomic age under these lines.) As long as fire remains in the leader’s hands alone—unless and until Za learns to share the gift given to him—the tribes of that world will be doomed to mistrusting, betraying, fighting, and murdering each other.

When I asked my ten-year-old son, after he’d seen the first hour of the story, what he thought would happen, he predicted Za and Kal would find a way to work together. I wish it were so! A little child leads…

For all that, I’m still asking: “Why hasn’t it changed?”

I wonder if the key isn’t in another one of the moments that shone for me—and not only because it marks the first on-screen use of the word “companion” in Doctor Who. The Doctor tells Barbara, “Fear makes companions of us all… Fear is with all of us and always will be. Just like that other sensation that lives with it … Hope.” How interesting that the Doctor is quick to name “fear,” but has to fumble before he comes up with the name of “hope.” His words suggest that, were human existence pictured as an ellipse, fear and hope would be the foci.

I wonder if the key isn’t in another one of the moments that shone for me—and not only because it marks the first on-screen use of the word “companion” in Doctor Who. The Doctor tells Barbara, “Fear makes companions of us all… Fear is with all of us and always will be. Just like that other sensation that lives with it … Hope.” How interesting that the Doctor is quick to name “fear,” but has to fumble before he comes up with the name of “hope.” His words suggest that, were human existence pictured as an ellipse, fear and hope would be the foci.

Is that an accurate image? Are we forever trapped between these two extremes? It might easily be so. As Carl Sagan once noted, we are all time travelers—we simply move in one temporal direction only: forward. Year by year, day by day, minute by minute, we move into the future; and as a wise Klingon chancellor once observed (if you’ll forgive my jumping franchise tracks for a moment), the future remains a fundamentally “undiscovered country.” We’re this time-travelling tribe together, we humans, making the choice, moment by moment, to face the future with fear or with hope. As the Doctor observes, the two sensations live together, jostling with each other for supremacy.

We did, however, for a few decades in first-century Palestine, have another companion (the word literally means “bread sharer”): someone who joined the human tribe temporarily… who “tabernacled” or “pitched his tent” with us… who showed us a way to move forward more in hope than in fear… who was, and still is, that Way himself. When we enter his story, we learn to face the future with more hope than fear, because he is not only the Way but also the destination.

Fear and hope also seem to be at the heart of the ongoing story that is Doctor Who, especially when the former gives way, suddenly and unexpectedly, to the latter. Granted, in “An Unearthly Child,” hope seems restricted to the Doctor and his companions finally making their getaway…but it’s a start. Until the coming of the new heavens and the new earth, the world will always need stories where fear is trumped by or even transformed into hope—and maybe that’s why Doctor Who “hasn’t changed.”

3 comments on “Retro TARDIS Talk: “An Unearthly Child” (Story 1: November 23-December 14, 1963)”