Ask a Batman fan why the Dark Knight is his or her favorite superhero, and you’re likely to hear some variation on this theme: if we wanted to, we could be Batman. Given enough time, enough disciplined training, and enough money, we could transform ourselves, as did Bruce Wayne, into caped crusaders, meting out justice on the city’s mean streets, putting superstitious and cowardly criminals in their place. It would be hard, but we could do it. That possibility is what makes Batman (ostensibly) one of the more realistic comic book crime fighters. No flight or super speed, no magic lasso or alien power ring required. Batman is really like us, and we could, theoretically, be like him.

Ask a Batman fan why the Dark Knight is his or her favorite superhero, and you’re likely to hear some variation on this theme: if we wanted to, we could be Batman. Given enough time, enough disciplined training, and enough money, we could transform ourselves, as did Bruce Wayne, into caped crusaders, meting out justice on the city’s mean streets, putting superstitious and cowardly criminals in their place. It would be hard, but we could do it. That possibility is what makes Batman (ostensibly) one of the more realistic comic book crime fighters. No flight or super speed, no magic lasso or alien power ring required. Batman is really like us, and we could, theoretically, be like him.

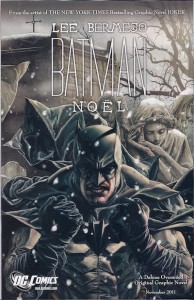

Lee Bermejo’s beautiful new graphic novel, however, asks us to consider that transformation’s cost.

Back in September, DC Comics solicited Batman: Noel in a way that made me think it would be little more than yet another reimagining of Charles Dickens’ remarkably malleable A Christmas Carol (1843), with Batman approximating the role of Scrooge: “Batman must come to terms with his past, present and future as he battles villains from the campy 1960s to dark and brooding menaces of today.” A clever conceit, I thought, but nothing too special. I could not have been more wrong. The solicitation text does about as much justice to Bermejo’s accomplishment as would calling 2001: A Space Odyssey “a story about a space mission that goes terribly wrong.” And, not unlike Kubrick and Clarke’s masterpiece, Batman: Noel is a visually stunning journey through significant themes that requires—and rewards—attention to detail, repeated exposure, and independent thought.

No, I’m not overstating the case. It’s just that good.

“Ol’ Scroogey”

The book’s plot is straightforward enough: Batman is hunting down the Joker. He uses Bob—a low-level Wayne Industries employee and single dad who is so desperate for money to treat his gravely ill son, Tim, that he moonlights as one of the Joker’s gophers—as bait for his nemesis, betting that the Joker will show up when Bob’s delivery of cash doesn’t.

The book’s plot is straightforward enough: Batman is hunting down the Joker. He uses Bob—a low-level Wayne Industries employee and single dad who is so desperate for money to treat his gravely ill son, Tim, that he moonlights as one of the Joker’s gophers—as bait for his nemesis, betting that the Joker will show up when Bob’s delivery of cash doesn’t.

But Noel isn’t really about how Batman foils another of the Joker’s schemes. It’s really about how Bruce Wayne’s dawning realization that his war on crime has, over time, made him as much of a misanthrope as Dickens’ penny-pinching miser—and maybe even more of one, because readers see that the man Bruce Wayne hates most is himself.

Bermejo drives this lesson home by having the book’s narrator (whose identity I won’t spoil—at the end, when I learned to whom I’d been “listening,” I immediately wanted to read the book again) recount A Christmas Carol in broad strokes, through well-chosen words that highlight similarities between Scrooge and Bruce, both as billionaire and as Batman. (Whether the narrator knowingly makes these comparisons remains ambiguous, and is part of the text’s genius).

For example, we read this as we descend, with Alfred, into the Batcave:

His place was dark and damp. As dingy, dim and empty as his heart, some might say. He liked it that way. See, ol’ Scroogey wasn’t very good with people. He preferred solitude. He had spent most of his life completely obsessed with his work. There wasn’t time for anyone else. Other people just seemed to be a nuisance.

Bermejo pulls off such juxtapositions time and again in Noel, proving both the mythic, universal quality of Dickens’ original story as well as his own skill as a teller of tales.

That’s Your Story… Are You Sticking To It?

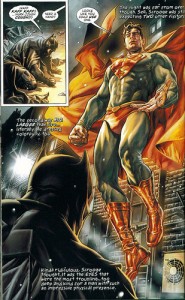

For Noel is also about storytelling—namely, the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves. A key sequence that develops this theme is Batman’s encounter, in a gloomy, snow-filled Gotham alley, with a warm, luminous Superman, who (unknowingly—or knowingly?—playing the part of the light-bringing, larger-than-life Ghost of Christmas Present) flies the world’s greatest detective around the city to show him things about which he previously hadn’t a clue. Outside Commissioner Gordon’s window, Batman hears, for the first time, the top cop’s doubts about him. Our narrator comments that

For Noel is also about storytelling—namely, the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves. A key sequence that develops this theme is Batman’s encounter, in a gloomy, snow-filled Gotham alley, with a warm, luminous Superman, who (unknowingly—or knowingly?—playing the part of the light-bringing, larger-than-life Ghost of Christmas Present) flies the world’s greatest detective around the city to show him things about which he previously hadn’t a clue. Outside Commissioner Gordon’s window, Batman hears, for the first time, the top cop’s doubts about him. Our narrator comments that

these people that Scrooge knew in his everyday life, these familiar faces, weren’t as familiar behind closed doors. He always considered himself a pillar of his community. An important person that people respected. It seemed that others didn’t necessarily share this opinion.

In Noel, Bruce must ultimately decide whether and how to change himself by changing the story by which he lives.

The story, understand, not its constituent biographical facts. Bermejo briefly but deftly revisits some fixed points in the Batman mythos. He depicts the murder of Thomas and Martha Wayne (without resorting to the visual cliché of Martha’s broken string of pearls), and strongly suggests Jason Todd’s devastating demise at the Joker’s (and comic book readers’) hands. He also includes glimpses of Batman and Robin in their early days—presumably “the campy 1960s” of DC’s solicitation, although the point is not to evoke Silver Age silliness but to highlight how Bruce’s crusade against crime has corrupted his spirit:

He was a younger man, then. Life still seemed like it was full of hope. Hope for the future. Hope for change… Anything seemed possible. Things that would appear ridiculous to ol’ Scroogey now were just roads to be taken, yet to be explored and conquered.

If Bruce is to recover the hope he has lost—if he is to avoid being remembered, in a possible, anarchy-filled future that would fit Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns, only as a vigilante bruiser out to “decrease the surplus criminal population” by any means necessary—then he must weave the facts of his life and career into a new narrative, a redemptive recitation. Like Dickens’ Scrooge, Bermejo’s “Scrooge” has a chance to revise the writing on his headstone. This chance is not simply handed to him, however. As our narrator asks us, “If you had the chance to change… to get it right… would you fight for it?” How Bruce answers that question, and his answer’s repercussions, drive the book to a dramatic and emotionally satisfying conclusion.

So You Want to Be Like Batman?

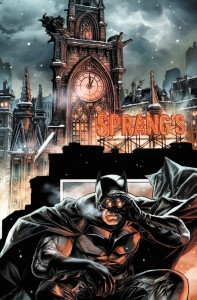

I lack the technical language needed to describe Bermejo’s outstanding artwork. Page after page of lush, richly detailed settings and characters, wonderfully colored by Barbara Ciardo, draw us into a fully realized Gotham City at Christmas, from the weathered and worn Santa Claus billboard to the worn-out but perseverant charity bell-ringer, all seen through the haze of a snowfall that looks like ash. (I did notice that Gotham’s population appears almost entirely Caucasian; I think I’ve spotted one non-Anglo face. This lack of diversity seems problematic, given that Superman at one point delivers a speech about the need for heroes to show people “the face of someone exactly like them.”)

I lack the technical language needed to describe Bermejo’s outstanding artwork. Page after page of lush, richly detailed settings and characters, wonderfully colored by Barbara Ciardo, draw us into a fully realized Gotham City at Christmas, from the weathered and worn Santa Claus billboard to the worn-out but perseverant charity bell-ringer, all seen through the haze of a snowfall that looks like ash. (I did notice that Gotham’s population appears almost entirely Caucasian; I think I’ve spotted one non-Anglo face. This lack of diversity seems problematic, given that Superman at one point delivers a speech about the need for heroes to show people “the face of someone exactly like them.”)

Bermejo also expertly depicts all the iconic characters. His style predominantly reminds me of Alex Ross’ realism, but with generous dollops of Norman Rockwell or Arthur Rackham as needed. Only Bob consistently looks “off” and “cartoony” to me—but Bermejo is probably using Bob’s overly large nose and bug-out eyes to underscore a thematic point, for this frantic father stands in as much need of a new narrative, a new story, as does Bruce Wayne.

While Bermejo’s Batman is, of course, easily recognizable physically, he didn’t instantly seem familiar to me. I knew Batman could be brooding and gritty, of course—since the late 1980s, he has usually been only that—but Bermejo allows us to peer into his psyche in a way that I, at least, never really had before.

That’s the reason I say Noel confronts us with the full price Bruce Wayne has paid to become Batman, and asks us to ponder, along with him, whether that price has been worth it.

The narrator ends his story by directly challenging us to identify its moral. I wonder if the moral might not be stated as something like this: Real change is necessary, but real change is costly, so be sure you are changing into somebody who’s worth the price and the pain. And Batman—at least as he is at the book’s outset—may not be the best choice of someone to be like, go-to answers for the character’s popularity notwithstanding.

Can People Change?

As Noel begins, the narrator cautions us that “for this story to make sense… for it to mean anything… you have to believe in something. Something very important. You have to believe people can change.” Dickens’ Christmas Carol persists, I think, because we do want to believe that people can change. We want to believe that the Scrooges of our world can transform from skinflints to saints, and overnight, if at all possible, please. Of course, not all of them do. What’s more, we continue to struggle, just as Bruce and Bob in Noel struggle, with the ways we want and need to change.

The good news of Christmas—that “first noel” sung by the angels—is that “to [us] is born this day in the city of David a Savior, who is the Messiah, the Lord” (Luke 2.11, NRSV). Devout first-century Jews reserved the word “Lord” for God. The angelic noel is thus even more astounding than it first may sound. God is born to us. God is with us—Emmanuel (see Matthew 1.22-23)! And because God is with us, we can be with God: in the next life, to be sure, but beginning here and now, in this one. Because God is dwelling among us, as one of us, full of grace and truth (see John 1.1-5, 14), we can change into the people God created us to be all along.

Left to our own devices, we may or may not change, and those changes may or may not stick. But when we receive Christ and believe in his name, we change in a fundamental way: we receive power to become God’s children (John 1.12). Put another way, we finally begin becoming fully human, free from the aberration of sin. We begin to become fully human—those who live life in God’s presence in this world and the next—because God became fully human in Jesus.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the pastor and theologian and martyr in Nazi Germany, wrote:

Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the pastor and theologian and martyr in Nazi Germany, wrote:

The figure of Jesus Christ takes shape in human beings… Human beings become human because God became human, but human beings do not become God. They could not and cannot bring about that change in their form, but God himself changes his form into human form, so that human beings—though not becoming God—can become human. (Quoted in God is in the Manger: Reflections on Advent and Christmas, Westminster John Knox Press, 2010; p. 52)

How do Christians answer the narrator of Noel? Yes, we believe people can change. But, while we may have to grab our chances to fight for penultimate changes, important as they can be, we can only receive our chance at ultimate change as a gift, a gift given in Bethlehem two thousand years ago.

Merry Christmas, and may God bless us, every one—even “Ol’ Scroogey” Batman.

Great review of a great book. The main hing hat stood out to me which I didn’t hear highlighted in the review is the way that the story deals with the roots of why people often become involved in criminal activity. The answer is clarly show as poverty and an unbroken cycle connected with poverty. Bon is not an evil man, yet circumstances force him to make an immoral choice to work for an immoral man, but for a moral reason…his son and a father’s need to care for and support his family.

I find this story especially poignant in economic times like ours when so many of us fail to see the root causes of terrorist and acts of crime often stem from a person’s impossible situation in life where they feel trapped to make any other choice but the wrong one, even though they don’t want to.

Thank you for your stellar review. I really loves this book.

Blessings,

Rick

Great review of a great book. The main thing that stood out to me which I didn’t hear highlighted in the review is the way that the story deals with the roots of why people often become involved in criminal activity. The answer is clarly show as poverty and an unbroken cycle connected with poverty. Bob is not an evil man, yet circumstances force him to make an immoral choice to work for an immoral man, but for a moral reason…his son and a father’s need to care for and support his family.

I find this story especially poignant in economic times like ours when so many of us fail to see the root causes of terrorist and acts of crime often stem from a person’s impossible situation in life where they feel trapped to make any other choice but the wrong one, even though they don’t want to.

Thank you for your stellar review. I really loves this book.

Blessings,

Rick

Rick – You’re right, I didn’t get into the aspect of how Bob got trapped (or trapped himself) in his predicament, but I agree: he isn’t evil, and the connection the book shows between crime and poverty is sharp and poignant. I also appreciate your application of that insight to our world today. Thanks so much for taking the time to read and comment on the review! As I said, I like this book better each time I read and think about it. I really think it’ll stand the test of time and be remembered by comic fans (and hopefully even a wider audience) for many Christmas seasons to come!