James T. Kirk isn’t a Christian character, but he just may be a model for those called to preach the Word.

If you’re a sci-fi Christian who isn’t also reading Scott Higa’s excellent blog The Christian Nerd, you really should be. Scott started his musings on “nerd culture from a Christian perspective and vice versa” around the same time our own Matt Anderson and Ben De Bono launched the SFC podcast. God was busy raising up geeks for His glory last year!

In a recent post, Scott pointed to Commander Adama’s rousing speech near the end of the Battlestar Galactica miniseries (2003), in which Adama inspires his ragtag fleet to search for the fabled planet Earth, as a model worthy of preachers’ consideration: “Adama’s speech does everything a sermon should.”

In a recent post, Scott pointed to Commander Adama’s rousing speech near the end of the Battlestar Galactica miniseries (2003), in which Adama inspires his ragtag fleet to search for the fabled planet Earth, as a model worthy of preachers’ consideration: “Adama’s speech does everything a sermon should.”

Scott’s suggestion got me wondering: What science fiction speech would I want preachers to look at, listen to, and learn from?

I don’t exempt myself, by the way, from the need to learn about preaching. I no longer preach on a weekly basis, but I did so for seven years, and still occasionally do. While I’ve always enjoyed preaching, I’ve no illusions that I’m a master of it. So, as I thought about Scott’s post, I knew that whatever speech I ended up “assigning” preachers, I’d be assigning it to myself, as well.

Unsurprisingly, my thoughts turned to Star Trek.

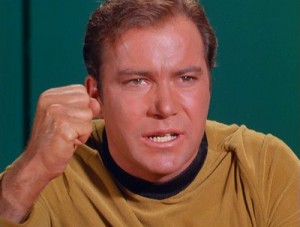

Now, not much preaching goes on in Gene Roddenberry’s wonderful but thoroughly secular humanist vision of the future. Federation starships’ crews don’t include chaplains (although the original Enterprise did have a chapel, and I don’t just mean Nurse Christine). Even so, inspiring and challenging oratory seems a prerequisite for Starfleet captains. Picard (especially Picard), Sisko, Janeway, Archer—they all make many fine speeches out there on the final frontier. For my quatloos, however, not one comes close to the speech Captain James T. Kirk makes in “Return to Tomorrow,” an otherwise ho-hum episode from the original series’ second season (first broadcast February 9, 1968).

Let me set the scene. The Enterprise crew has discovered three survivors of an incredibly ancient alien race who are by now nothing more than disembodied minds. The aliens have, therefore, requested the temporary use of three crew members’ bodies—Kirk, Spock, and Dr. Ann Mulhall (played by guest star and future Next Generation second season regular Diana Muldaur)—in order to build permanent, robotic shells for themselves. In exchange, the aliens will share their advanced technology and knowledge with humanity.

Not everyone is convinced this risky loan of life and limb is a good idea. Kirk, however, finds the idea compelling—and so, in this speech, he makes his case:

Make any wisecracks you want about the cheesy music or Shatner’s hallmark halting speech pattern. I stand by my assertion that this speech is not only one of the original series’ finest moments (apart from the “to boldly go” opening narration; it’s arguably the purest statement of the show’s philosophy) but also a mini-master class in homiletics.

So what should those who preach sermons—and those who listen to them—note here?

Kirk “casts a vision.” That’s Scott Higa’s phrase, and it’s a great one. Preachers must present their hearers with a vision of an alternate reality: the real but only sporadically visible, present but yet-to-come reality of God’s kingdom, God’s fully realized rule over all creation. Preachers don’t dream up this vision for themselves. Like the apostle John, they act as witnesses, declaring “what we have heard, what we have seen with our eyes, what we have looked at and touched with our hands, concerning the word of life” (1 John 1.1). They testify to the ways they have seen Jesus Christ—in their study of the Scripture, in their lives and the lives of those to whom they preach, in the culture and in the world—and, by the grace and power of the Holy Spirit, their testimony creates an opportunity for others to see Jesus for themselves. As the neighbors of that Samaritan woman at the well told her, after her testimony provoked them to seek out Jesus, “It is no longer because of what you said that we believe, for we have heard for ourselves, and we know that this is truly the Savior of the world” (John 4.42). She was one of the first Christian preachers!

This being Star Trek, of course, the vision Kirk casts is not of God’s kingdom—but it is a vision full of new beginnings and new possibilities, “the potential for knowledge and advancement.” Through concrete examples—the old saw about “If man had been meant to fly…,” the success of the Apollo space program, the relative barbarism of Bones’ medical forebears—Kirk redirects his crew’s vision from immediate, short-term danger to greater, long-term gain. He speaks as noted biblical scholar and preacher Walter Brueggemann calls on his fellow preachers to speak, with “shattering, evocative speech that breaks fixed conclusions and presses us always toward new, dangerous, imaginative possibilities,” all grounded in the good, ground-shaking news of God’s action in Jesus Christ (Brueggemann, Finally Comes the Poet, Fortress Press, 1989, p. 6). Kirk casts that kind of vision—“Risk is our business!”—and his crew catches it.

Kirk humbly speaks the truth. I know, nothing about Shatner’s performance here immediately suggests humility. (Nothing about Shatner in general suggests humility—as witnessed by his current one-man show—but that’s beside the point.) But I don’t think Kirk is merely employing manipulative rhetoric when he says, “I’m in command. I could order this. But I’m not.” Whatever their tradition, from the highest of high-church priests garbed in alb and chausable to the pastor of the storefront church in simple coat and tie, preachers carry a certain weight of authority by virtue of their role. And whether it is theologically validated or liturgically legitimated in their communities, preachers inevitably wield a certain amount of power. That’s just social dynamics. The question is, will preachers abuse that power and authority, or will they obey Jesus’ word and refuse to “lord it over” the people they serve (Mark 10.42).

Kirk exercises humility by inviting his crew to participate in this venture, rather than insisting that they do. He acknowledges Dr. McCoy’s objections—more than that, he affirms them, to a point. He doesn’t deny the reality of the situation. And so he models how preachers can exercise their authority humbly: by acknowledging the realities facing their listeners that might hinder their favorable response to th e Gospel. A preacher who is so full of confidence in God’s Word—or, worse, so enamored of the pulpit’s inherent authority or power—that she or he leaves no room for other voices to be heard serves no one. The preacher does not, of course, give the same weight to those other voices, any more than Kirk concedes his argument. But the preacher can anticipate and, to some extent, affirm objections, questions, doubts, and fears, all without compromising the truth or the power of the Gospel. Isn’t this, in part, why the risen Jesus was willing to meet Thomas’ demand to see the scars of the crucifixion, even while urging him, “Do not doubt but believe” (John 20.27)? Because Jesus acknowledged and affirmed the truth of Thomas’ situation, rather than running roughshod over it in Resurrection righteousness, the doubting disciple could make the climactic confession of faith in the Fourth Gospel, “My Lord and my God!” (20.28). Jesus invited—he did not insist.

e Gospel. A preacher who is so full of confidence in God’s Word—or, worse, so enamored of the pulpit’s inherent authority or power—that she or he leaves no room for other voices to be heard serves no one. The preacher does not, of course, give the same weight to those other voices, any more than Kirk concedes his argument. But the preacher can anticipate and, to some extent, affirm objections, questions, doubts, and fears, all without compromising the truth or the power of the Gospel. Isn’t this, in part, why the risen Jesus was willing to meet Thomas’ demand to see the scars of the crucifixion, even while urging him, “Do not doubt but believe” (John 20.27)? Because Jesus acknowledged and affirmed the truth of Thomas’ situation, rather than running roughshod over it in Resurrection righteousness, the doubting disciple could make the climactic confession of faith in the Fourth Gospel, “My Lord and my God!” (20.28). Jesus invited—he did not insist.

Kirk speaks with passion. Again, you may feel Shatner’s performance is over the top, and I wouldn’t advise preachers to emulate his distinctive style in the pulpit. (Trust me on this: I tried a Shatner impression mid-sermon one time, and let’s just say it wasn’t one of my finer pastoral moments). There’s no denying, however, that Kirk feels passionately about this mission. As science fiction author Robert J. Sawyer says, “Shatner is so terrific [in this scene], actually, that one forgets that the owners of the three borrowed bodies almost end up killed, one of the aliens commits murder, two die by suicide, and no scientific wonders are ever bestowed.” Oh, well. The episode’s subsequent plot negates neither Kirk’s points, nor the passion with which he makes them.

Preachers must preach with passion. They don’t have to preach in perpetually breathless tones, or with wild waving of the hands, or with numerous poundings of the pulpit. Passion can also be communicated in a softly and slowly spoken sentence, or with a broad and warm smile, or in a silent and steady gaze. Being dramatic isn’t the point. Shatner is acting; Kirk is not. Kirk expresses himself directly and authentically, and that is no small part of his speech’s power. He believes what he’s saying, and, as Sawyer also says, by the time he’s done, his crew—and we—believe it, too: we’re “left thinking that Kirk was… right to push for the advancement of science, the risks be damned. Anything less would be a betrayal of the human spirit.”

Preachers must preach with passion. They don’t have to preach in perpetually breathless tones, or with wild waving of the hands, or with numerous poundings of the pulpit. Passion can also be communicated in a softly and slowly spoken sentence, or with a broad and warm smile, or in a silent and steady gaze. Being dramatic isn’t the point. Shatner is acting; Kirk is not. Kirk expresses himself directly and authentically, and that is no small part of his speech’s power. He believes what he’s saying, and, as Sawyer also says, by the time he’s done, his crew—and we—believe it, too: we’re “left thinking that Kirk was… right to push for the advancement of science, the risks be damned. Anything less would be a betrayal of the human spirit.”

In his ministry, the apostle Paul did not worry about eloquence or theatrics. He reminds the early Christians in Corinth, “I did not come proclaiming the mystery of God to you in lofty words of wisdom. For I decided to know nothing among you except Jesus Christ, and him crucified. And I came to you in weakness and in fear and in much trembling. My speech and my proclamation were not with plausible words of wisdom, but with a demonstration of the Spirit and of power, so that your faith might rest not on human wisdom but on the power of God” (1 Cor. 2.2-5). Paul may be referring to miracles he performed, but he may simply mean that, because he spoke out of his simple and authentic passion for the Gospel (see Rom. 1.16-17), he gained the Gospel a powerful hearing. As N.T. Wright comments, “The truth of the gospel carried its own power, and Paul was happy to keep it that way, even though he looked like a fool while he was announcing it” (Paul for Everyone: 1 Corinthians, Westminster John Knox Press, 2004, p. 21). (I wonder if first-century stand-up comics did Paul impressions the way comedians do Shatner impressions today?)

The preacher’s passion, of course, doesn’t guarantee God’s Word will be heard, or that listeners will respond favorably. Paul himself experienced this truth in Athens: he surely spoke with passion, yet only “some of [the Athenians] joined him and became believers” (Acts 17.34). Only God gives God’s Word success (see Isaiah 55.10-11). But preachers must passionately believe that, every time they preach, God may choose to use their words to awaken and nurture the response of faith in those who hear.

That’s a lot to wring out of less than two minutes of screen time, but I do think preachers could learn quite a bit from James T. Kirk. What sci-fi or fantasy speechmaker would you like preachers to learn from?

I should also add that all Christians, preachers or not, have been called to proclaim the Gospel. Captain Kirk’s impassioned plea for taking risks thus relates to every follower of Jesus. Speaking about Christ, acting in Christ’s name, staying true to Christ in your own life—all that can be risky business. And yet he has told us it is a risk well worth taking: “For those who want to save their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake, and for the sake of the gospel, will save it” (Mark 8.35).

People of God: risk – (Shatnerian pause) is our business, too!

All Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version.

Featured Image of Captain Kirk found at http://sfwriter.com/2008/06/risk-is-our-business.html.

Caravaggio, “The Incredulity of Saint Thomas,” c. 1602; image found at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Caravaggio_-_The_Incredulity_of_Saint_Thomas.jpg.

That speech gives me chills every time!

This is a great article – if only for convincing this lifelong Trek fan that Kirk is humble.

I can’t believe a Shatner impression didn’t fly during your sermon. 😉

Anyway, thanks for the boost and the reminder – RISK…is our business. That’s what this church is all about!

Thanks for reading, Mickey! Re: the Shatner impression – fortunately, the congregation and I had known each other for several years at that point. I wouldn’t dared have tried it otherwise! But, still, no, not something I’d recommend. Unless maybe you’re Kevin Pollak. 😉

Great essay, Michael! You do a really nice job at explaining Kirk’s speech in way that allows the reader to not even hear the speech (which at the moment I can’t due to a double ear infection). Certainly, I will check it out once I can hear again and no doubt, your opinion will stand true.

Thanks for the kind words, Max – and get better soon!

Many thanks to Mickey for giving this post a shout-out at his blog, Geeks of Christ (http://geeksofchrist.wordpress.com/2012/03/16/geeks-of-christ-presents-march-2-2012/). If you haven’t checked his great essays over there out yet … well, get on the stick, why don’t you? 😉