Rewatching “Skin of Evil” reminded me of an incident from seminary. On the first day of a course about loss and grief, our professor gave us an unusual assignment: he wanted us to plan our own funeral.

Rewatching “Skin of Evil” reminded me of an incident from seminary. On the first day of a course about loss and grief, our professor gave us an unusual assignment: he wanted us to plan our own funeral.

I don’t know how you’d approach a task like that, but I, with my keen interest in all things liturgical, immediately started scouring prayer books for just the right words and hymnals for just the right music. I was very concerned that my funeral service be (as my denomination encourages calling it) a Service of Witness to the Resurrection. I wanted the focus to rest squarely on God, not on the late Mike Poteet. As I wrote the service, I chose Scripture readings, a congregational affirmation of faith, even choir anthems and organ voluntaries that I thought served to proclaim the great hope the risen Jesus gives us: “I am the resurrection and the life. Those who believe in me, even though they die, will live, and everyone who lives and believes in me will never die. I was dead, and see, I am alive forever and ever. Because I live, you also will live” (John 11.25-26; Rev. 1.18; John 14.19). I turned in my funeral plans confident that I’d crafted a liturgically elegant and theologically correct worship experience.

The professor didn’t grade these papers, but he did return them with notes, and on my funeral plan he wrote: “You show great appreciation for the power and beauty of the church’s worship, but do you think you may have rushed to resurrection too soon?”

I still remember how outraged I was. Rushing to resurrection? What was that supposed to mean? Did this guy not believe in the resurrection? Didn’t he know that the “sure and certain hope of the resurrection” (love that Book of Common Prayer language!) is at the heart of our religion? Hadn’t he read the apostle Paul: “If Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile, and you are still in your sins… If for this life only we have hoped in Christ, we are of all people most to be pitied” (1 Cor. 15.17, 19)? Was this guy really even a Christian?

My self-righteous indignation over my professor’s critique weren’t that far removed from the reactions I had to “Skin of Evil” when it first aired.

I liked the episode—in fact, I still do. Armus isn’t an especially scary monster to look at, but as a concept, he is convincingly terrifying. Marina Sirtis does some fine acting, finally given the chance to use her character’s empathic abilities in meaningful ways. And composer Ron Jones provides another unforgettable score.

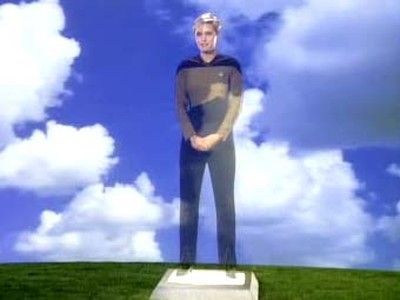

But it’s the holodeck memorial service for Tasha, of course, that makes “Skin of Evil” a Star Trek milestone.

Here was no “redshirt,” no conveniently forgettable casualty. For all that Denise Crosby felt underused and underappreciated, she had, in just a few months’ time, created a character that fans would really miss. And we knew, even in those pre-Internet days, that Tasha’s death was the real deal. News of Crosby’s decision to leave the show made major media headlines. She would not be back next week, and this development was unprecedented. No major, regular Star Trek character had ever before died and stayed dead. Yes, I know, “Yesterday’s Enterprise” must be reckoned with—but that Tasha came from an alternate timeline. The “real” Tasha, our Tasha, never returned. How she died marked a departure for Star Trek, too. Her death was sudden, senseless—and a serious reminder that, as Captain Kirk once said, risk is Starfleet’s business. “Yesterday’s Enterprise” is one of my favorite TNG episodes, but simply because it’s a great story, not because it supposedly “redeems” Tasha’s death. Tasha’s death needs no redemption. As she says in her recorded message, she died doing exactly what she’d chosen to do. She knew and accepted the danger of her duty. She met death with eyes wide open.

Like many other fans, I tear up watching Tasha’s farewell speech, every time. It’s a beautiful sequence. But when I first saw it, I felt that familiar twinge of tension I sometimes feel as a Christian Trekkie. I listened to Tasha’s definition of death—and, by implication, of immortality—and thought, “How sad.” You’ll remember, Tasha says, “Death is that state in which one exists only in the memory of others—which is why it is not an end. No goodbyes. Just good memories.” These words really stuck in my teenaged Christian craw. What was it with Roddenberry and this über-humanistic future he longed for? What was this supposed to mean, this New Age-sounding pablum about “good memories”? Of course there was more to the afterlife than that! Why couldn’t he just believe the sure and certain hope of the resurrection? Surely he’d be so much happier if he were a Christian!

Like many other fans, I tear up watching Tasha’s farewell speech, every time. It’s a beautiful sequence. But when I first saw it, I felt that familiar twinge of tension I sometimes feel as a Christian Trekkie. I listened to Tasha’s definition of death—and, by implication, of immortality—and thought, “How sad.” You’ll remember, Tasha says, “Death is that state in which one exists only in the memory of others—which is why it is not an end. No goodbyes. Just good memories.” These words really stuck in my teenaged Christian craw. What was it with Roddenberry and this über-humanistic future he longed for? What was this supposed to mean, this New Age-sounding pablum about “good memories”? Of course there was more to the afterlife than that! Why couldn’t he just believe the sure and certain hope of the resurrection? Surely he’d be so much happier if he were a Christian!

What I wasn’t then fully appreciating was the immense value of what Tasha had obviously done in planning her own funeral. “What I want you to know,” she says, “is how much I loved my life, and those of you who shared it with me. You are my family… I have been blessed with your friendship and your love.” Tasha knew her friends would need to grieve, and so the last gift she gave them was permission to do so.

This point, of course, was the point my seminary professor was trying to make. I didn’t get it until I was serving a congregation as pastor.

There’s an anecdotal theory in pastoral ministry that older church members in a congregation which is undergoing a transition in pastoral leadership will “hang on” until the new pastor arrives; once she or he is in the pulpit, they feel free to let go and die. Who knows? All I know is, I conducted a lot of funerals that first year; in fact, my first day on the job as a pastor, I had to conduct a graveside service. And I muddled through, reading the “right” Scriptures, and praying the “right” prayers… but the end result didn’t seem “right” overall.

A few months later, I had to lead the funeral of a long-time church member who was dying young, from cancer. He left behind a wife and two teenaged daughters. His family was, of course, devastated. The congregation was heartbroken. And, for some reason—I believe the Spirit stepped in, thank God, literally—during that service, as I could see this man’s youngest daughter sobbing out of the corner of my eye, I departed from my prepared remarks just long enough to say, “The people of God are never ashamed to show God their tears.” Now, I may or may not have been giving the congregation permission to grieve, but I knew I was giving myself permission to do so.

That experience has informed every funeral I’ve ever performed since. Don’t misunderstand: I always preached the resurrection. But I stopped “rushing” to it. Paul didn’t want the Thessalonians to “grieve as others do who have no hope” (1 Thes. 4.13)—but he didn’t tell them not to grieve at all. Christians grieve differently, but, of course, Christians grieve.

Tasha’s farwell, then, offers Christians a model for grief. Is it a perfect model? No. Even though I used to be quite “holier-than-Trek” about this episode, I do still believe its hope for immortality can’t compare to the hope we know in Jesus Christ, crucified and risen. But remember: while Jesus’ Resurrection is the defining word on the subject, Scripture doesn’t speak with one voice about what awaits us, or doesn’t, after death. Generations of God’s faithful people had no hope in a resurrection from the dead; not until the time of Daniel did this idea emerge in ancient Judaism (Daniel 12.2). Tasha’s hope in immortality through the memory of others was a hope shared by our patriarchs and matriarchs in the faith—but even that hope proved elusive for the Teacher, in Ecclesiastes: “For there is no enduring remembrance of the wise or of fools, seeing that in the days to come all will have been long forgotten” (Eccl. 2.16). Or what of the psalm-singers who confess, “As for mortals, their days are like grass; they flourish like a flower of the field; for the wind passes over it, and it is gone…” (Ps. 103.15-16)?

Again, I accept these testimonies as “minority reports.” But, as reports also accepted in the canon of Scripture, they must be reckoned with, not simply dismissed by “rushing to resurrection.” Do such testimonies offer any wisdom, any guidance, for Christians today?

I think they do. I think they urge us to pray, as the psalm-singer does, to pray that God will “teach us to count our days, that we may gain a wise heart” (Ps. 90.12). Our time on this earth is good—and it is finite. As the Teacher counsels, we should “be happy and enjoy [ourselves] as long as [we] live; moreover, it is God’s gift that all should eat and drink and take pleasure in all [our] toil” (Eccl. 3.12-13). In fact, we could argue that Christians responsibility to “seize the day” is enhanced, not diminished, by our faith in Christ, for God has chosen us in Christ not only for salvation tomorrow but also for service today—“for good works, which God prepared beforehand to be our way of life” (Eph. 2.10). James’ sober warning surely applies, as well: “Anyone, then, who knows the right thing to do and fails to do it, commits sin” (James 4.17). This life matters! We should celebrate it, and enjoy it, and work hard for God and for others in it.

And so it’s entirely appropriate that Tasha Yar tell her loved ones how much each one of the meant to her, and remember the good that they did and enjoyed together. Her farewell makes it clear that she lived a rich life, however brief. Her Enterprise family needs to hear that truth, and rejoice in it—and, yes, grieve its loss. So do we, when we lose loved ones, no matter how brief or long their lives might have been. We need to take the time to grieve. We need to share our sadness, with each other, and with God. We need also to give thanks for the good memories we have of those who die, for our belief that they rejoice “in a greater light, on a farther shore” doesn’t need to diminish the joy our memories of the time we had with them can bring. We need to laugh, to cry, to ponder… to experience the movement, so prevalent in Scripture, from darkness to light, from tears of sorrow to tears of gladness, from the fall of night to the break of dawn.

And so it’s entirely appropriate that Tasha Yar tell her loved ones how much each one of the meant to her, and remember the good that they did and enjoyed together. Her farewell makes it clear that she lived a rich life, however brief. Her Enterprise family needs to hear that truth, and rejoice in it—and, yes, grieve its loss. So do we, when we lose loved ones, no matter how brief or long their lives might have been. We need to take the time to grieve. We need to share our sadness, with each other, and with God. We need also to give thanks for the good memories we have of those who die, for our belief that they rejoice “in a greater light, on a farther shore” doesn’t need to diminish the joy our memories of the time we had with them can bring. We need to laugh, to cry, to ponder… to experience the movement, so prevalent in Scripture, from darkness to light, from tears of sorrow to tears of gladness, from the fall of night to the break of dawn.

Perhaps the truth is, we don’t need to rush to resurrection because, by God’s grace, resurrection rushes to us.

All Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version.

Next week: We warp ahead to season two, and a little child—“The Child,” in fact, the second season’s debut episode—shall lead us…

Leave a Reply