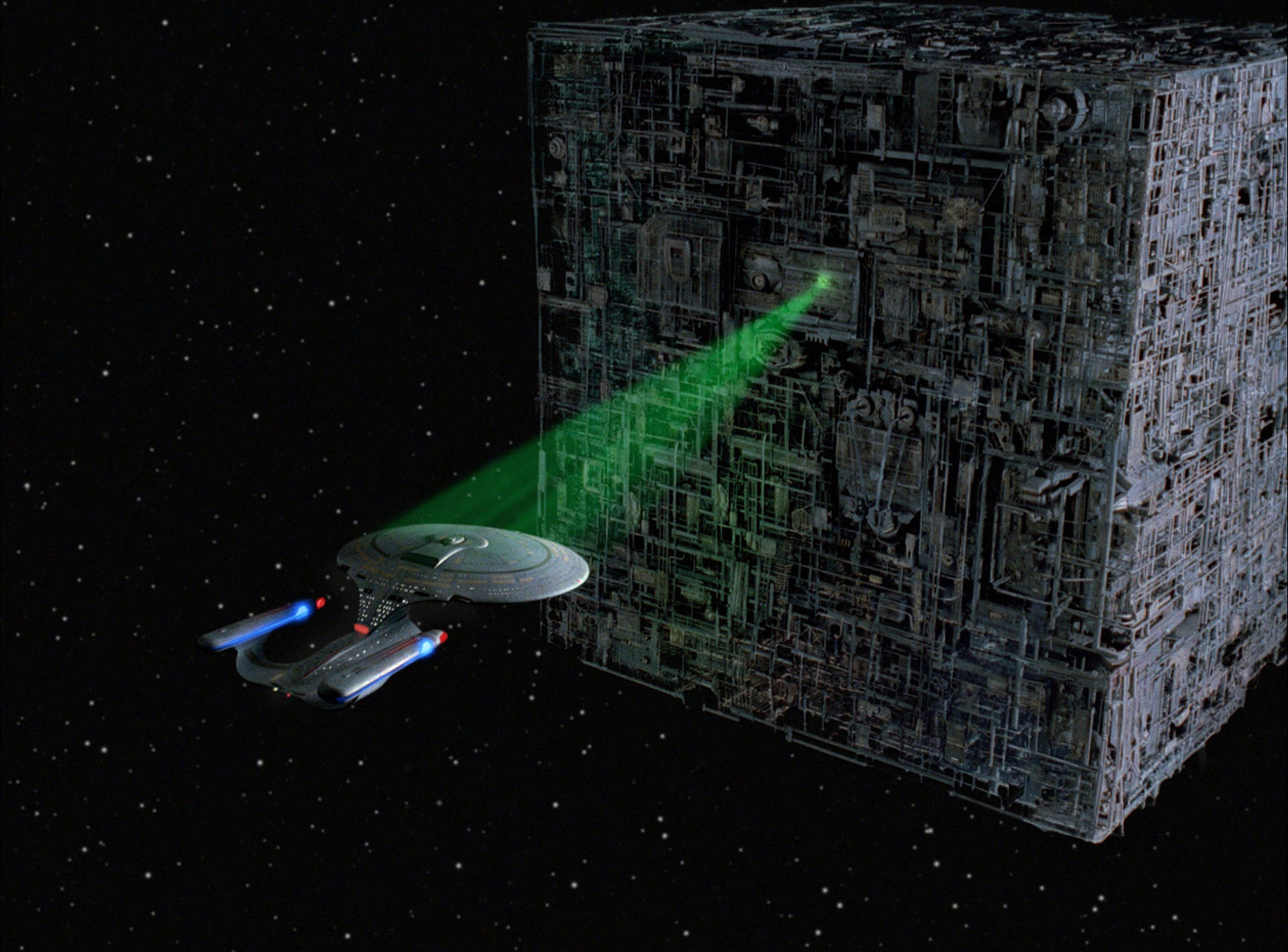

After “Encounter at Farpoint,” arguably no episode from TNG’s first two seasons proved as pivotal as “Q Who.” Its introduction of Ensign Sonya Gomez as a protégé (and, I suspect, potential love interest) for Geordi was doomed by rotten dialogue from the get-go (though actress Lycia Naff gave it her best shot; still, she’s perhaps best remembered by genre fans as the triple-breasted prostitute Mary in Total Recall—check IMDB; I don’t make this stuff up). The hints of centuries-old animosity between Q and Guinan are more intriguing, but (as far as I remember) never again surfaced onscreen. But “Q Who” gave Star Trek the Borg, and the franchise would never be the same. The relentless cybernetic zombie-vampires have become pop culture icons. They are one of the few Trek villains “everybody knows,” an elite club whose only other members, I would guess, are Khan and Klingons. Without “Q Who,” we would have no “Best of Both Worlds,” no First Contact, no Seven of Nine.

After “Encounter at Farpoint,” arguably no episode from TNG’s first two seasons proved as pivotal as “Q Who.” Its introduction of Ensign Sonya Gomez as a protégé (and, I suspect, potential love interest) for Geordi was doomed by rotten dialogue from the get-go (though actress Lycia Naff gave it her best shot; still, she’s perhaps best remembered by genre fans as the triple-breasted prostitute Mary in Total Recall—check IMDB; I don’t make this stuff up). The hints of centuries-old animosity between Q and Guinan are more intriguing, but (as far as I remember) never again surfaced onscreen. But “Q Who” gave Star Trek the Borg, and the franchise would never be the same. The relentless cybernetic zombie-vampires have become pop culture icons. They are one of the few Trek villains “everybody knows,” an elite club whose only other members, I would guess, are Khan and Klingons. Without “Q Who,” we would have no “Best of Both Worlds,” no First Contact, no Seven of Nine.

For that matter, I’d have no Hallmark Borg cube to hang on my Christmas tree! (This video is not mine, but I include it here because no one should go without seeing and hearing this piece of Yuletide cheer.)

Actually, that ornament’s existence illustrates what went wrong with the Borg. Resistance to their success proved futile. Umpity-ump iterations later (beginning about the time Lore showed up as a leader of a rogue Borg sect in season six of TNG, and culminating with “I Was a Teenage Borg” Icheb in the waning days of Voyager), the Borg had become domesticated. The techno-terrors had been tamed.

To watch “Q Who” now, therefore, is to be reminded of just flat-out scary the Borg originally were—“terrors to freeze your soul,” indeed, as Q tells Picard. In case you haven’t seen the episode recently, here’s another fan’s ten-minute refresher. See for yourself just how creepy the Borg could be:

No better adversary than the Borg could have been crafted for Star Trek, the franchise that so unswervingly celebrates the self-fulfilled individual and the glory of “the human adventure.” The Borg is a nameless, faceless mass of conformity that has sacrificed the individual at the altar of “the collective.” The Borg way of life (if it can be called that) is fundamentally abhorrent to the ethos of Starfleet.

Can’t Spell “Christian” Without an “I”

It is abhorrent to Christian ethos, too, though perhaps not quite for the same reasons. While classic Christian faith, as I understand it, doesn’t share Star Trek’s unbridled enthusiasm for and optimism about humanity, neither does it deny humanity’s unique and valued place, both in the creation and in the Creator’s sight. Fashioned in God’s image to be caretakers of the cosmos (Gen. 1.26-28; 2.15), we are “a little lower than God, and crowned… with glory and honor” (Ps. 8.5). What’s more, we have been given dignity and worth not only as the human race, but as particular peoples and individual members of it. The human race is no monolithic, homogeneous “collective,” but a vast and vibrant mix of families, all of whom take their name from one Father in heaven (see Eph. 3.14-15). And while God’s Church is a new family that finds in Christ there is no longer Jew or Greek, male or female (Gal. 3.28), these differences cease to divide: they do not disappear. The story of ancient Christianity is, in part, the story of people learning how to let God hold them together in the midst of ethnic, cultural, and linguistic differences (for example, the controversy over Peter’s baptism of Gentiles, recounted in Acts 10-11). Unity in Christ does not mean uniformity; common life and work in him does not mean conformity. Individualism is not the end-all and be-all of the Christian life, but we do believe God creates us as unique individuals (e.g., Ps. 139.13-14), all of whom we are to not only respect but love as ourselves (Matt. 22.39).

Jesus’ Great Commandment was not, “Thou shalt add thy neighbor’s biological and technological distinctiveness to thine own!”

“A Difficult Admission”

At various points in “Q Who,” Picard does what Picard does best: he tries to save himself and his crew through his own efforts. He politely but firmly orders the Borg scout in engineering to step away from the computer console. He assures the Borg that the Enterprise means them no harm. He asks Guinan how to reason with them—to which she replies, with a scoff, “You don’t.” Eventually, when the Borg cube is in hot pursuit, Picard resorts, in vain, to phasers and photon torpedoes. He orders Geordi to push the ship’s warp engines as far as possible—still it’s not enough. Salvation comes only when Picard appeals to the mercy of Q:

PICARD: Q, end this.

Q: Moi? What makes you think I am either inclined or capable to terminate this encounter?

PICARD: If we all die, here and now—you won’t be able to gloat! You wanted to frighten us? We’re frightened. You wanted to show that we are inadequate? For the moment, I grant that. You want me to say that I need you? I need you!

With a snap of Q’s fingers, the Enterprise is back where it is supposed to be. Wesley Crusher says it’s at “zero-seven-six mark two-two-five—back where we started.” In non-technobabble, that means safe, delivered from sure and certain destruction. Q tells Picard, “That was a difficult admission. Another man would be humiliated to say those words. Another man would die before asking for help.” (You can, and should, watch this scene for yourself starting at about 08:25 in the clip above—it’s well worth it, another fine moment from Patrick Stewart and John de Lancie.)

With a snap of Q’s fingers, the Enterprise is back where it is supposed to be. Wesley Crusher says it’s at “zero-seven-six mark two-two-five—back where we started.” In non-technobabble, that means safe, delivered from sure and certain destruction. Q tells Picard, “That was a difficult admission. Another man would be humiliated to say those words. Another man would die before asking for help.” (You can, and should, watch this scene for yourself starting at about 08:25 in the clip above—it’s well worth it, another fine moment from Patrick Stewart and John de Lancie.)

For my quatloos, that scene offers us sci-fi Christians a powerful parable of salvation. Not that Q comes even close as a true representative of God (we’ve dispatched that idea in our theological trek already), but in the truth that, like Picard, we are saved from sure and certain destruction only when we abandon all hope in our own efforts and call to God, “I need you!” Unlike Picard, however, we do so without qualification, without reservation. No “for the moment” will do. When we call for help, we call de profundis: “Out of the depths I cry to you, O Lord. Lord, hear my voice! Let your ears be attentive to the voice of my supplications!” (Ps. 130.1). Like the psalm-singer, we know that no one can stand before God on the grounds of supposed self-righteousness; as the beloved old hymn has it, we come before the Lamb of God just as we are, without one plea but that his blood was shed for us.

Sin pursues us even more determinedly than the Borg chase the Enterprise. It “clings so closely” (Heb. 12.1); like some ferocious beast, it “is lurking at the door,” desiring to devour us (Gen. 4.7). We are caught in the impossible situation of having to master it (as God told Cain), but always, inevitably, finding ourselves mastered by it instead. Sin threatens to “assimilate” us—to so twist our humanity, destroy our individuality, and obscure the image of God within us that, like any Borg drone, we are no longer recognizable as the people God made us to be. “Wretched man that I am!” Paul laments, wrestling with this reality. “Who will rescue me from this body of death?” (Rom. 7.24).

With his very next words, Paul answers his own question: “Thanks be to God through Jesus Christ our Lord!” (7.25a).

Faced with the threat sin and evil pose, we should be frightened. And we are inadequate, utterly incapable, of saving ourselves. We need a Savior who can deliver us. And so we call out, hoping that Savior will hear, “I need you!”

And that Savior does hear, and that Savior does deliver—not because of our cries, but because of his love. God “has rescued us from the power of darkness and transferred us into the kingdom of his beloved Son, in whom we have redemption, the forgiveness of sins” (Col. 1.13).

A “difficult admission,” to be sure. Have you ever really made it? Have I? I think it is likely an admission we must make again and again, not just once and for all. It doesn’t save us in itself, any more than anything else we can do on our own… but unless and until we can make it, we may never experience the gift of being back where we are supposed to be, back where we started, in a right relationship with God.

All Scripture quotations from the New Revised Standard Version.

Next Week: “Who Watches the Watchers?” Hopefully, you will, and you’ll leave your insights in the comments! See you then!

The Borg can be equated with sin. That’s a good analogy.

I assume you went to last night’s showing. Measure of a Man is a good partner to this episode.

‘Q Who’ admits weaknesses. As the director of this episode repeated a few times, this one introduces a problem and doesn’t solve it. Well, the characters have to survive their encounter with the Borg to get to next week’s episode, so how can they survive without solving the problem? They have to appeal to somebody bigger to help them out.

No, actually, my son had a band concert, so I couldn’t do the big-screen showing, though I would have enjoyed it.

You’re dead-on about the admission of weakness. It makes it a somewhat rare bird in Trek.

Thanks for reading and commenting!