Star Trek can serve up courtroom drama as riveting as anything the myriad Law & Order series have to offer (without, alas, Mike Post’s musical chung-chung). Captain Kirk took the stand several times (“Court Martial,” “The Deadly Years,” Star Trek IV, Star Trek VI), as did Spock on at least one memorable occasion (“The Menagerie”). One of Commander Sisko’s earliest duties on Deep Space Nine was serving as Dax’s defense attorney in an extradition trial (“Dax”).

TNG, too, took advantage of the dramatic possibilities inherent in a trial more than once, from Q’s post-apocalyptic judgment hall (“Encounter at Farpoint,” “All Good Things”), to overzealous Starfleet investigations (“Coming of Age,” “The Drumhead”), to the standout second season episode we consider today, an hour of Trek so intellectually absorbing and emotionally compelling it won its author, Melinda Snodgrass, a position as series story editor.

TNG, too, took advantage of the dramatic possibilities inherent in a trial more than once, from Q’s post-apocalyptic judgment hall (“Encounter at Farpoint,” “All Good Things”), to overzealous Starfleet investigations (“Coming of Age,” “The Drumhead”), to the standout second season episode we consider today, an hour of Trek so intellectually absorbing and emotionally compelling it won its author, Melinda Snodgrass, a position as series story editor.

In lesser hands, the tale of Data’s trial—and while the legal proceeding is, technically, a hearing, it is in truth a trial to settle the question of whether the android officer is a sentient being with the right of self-determination—might have been a simplistic affair full of cardboard characters spouting pompous clichés. Even Star Trek has had its fair share of such stories. But Snodgrass delivers a script that defies superficial viewings, and rewards repeated consideration.

For example, Commander Maddox (played by Brian Brophy), the cybernetics engineer who wants to dismantle Data in order to replicate “it,” is no mustache-twirling mad scientist, but an ambitious, intelligent and passionate researcher with sympathetic motives. Who can deny that an “army of Datas” could accomplish remarkable things on humanity’s behalf?

Or consider the scene in which Commander Riker—reluctantly pressed into service as the prosecutor who must prove Data is a mere machine and therefore Starfleet’s property—reviews the android’s schematics. We watch his face light up as he learns of Data’s “off” button—and then, in the next instant, cloud over and fall as he realizes he is (he thinks) clinching his case at the cost of sealing his friend’s fate. It’s just one memorable moment in an episode filled to overflowing with them. “The Measure of a Man” consistently ranks as a fan favorite, and deservedly so.

But what of the arguments it makes for Data’s sentience, rights, and freedom? Do they hold up from a sci-fi Christian perspective?

Is Something Troubling You?

Last week, I asked you for insights on this episode. Doug Payton (of “Consider This!”) was the first to speak up: “The ultimate argument for Data being self-aware was that he used personal pronouns. ‘I. Me. My. Certainly sounds self-aware.’ So did Eliza.”

Doug raises a point worth considering. ELIZA is, according to the Oxford Dictionaries blog, “a piece of software that attempts to simulate the conversation of a Rogerian psychotherapist” (in other words, actively listening to the patient’s attitudes and feelings in order to reflect them back in a non-judgmental, non-directive fashion, making space for the patient’s self-realizations). As a natural language processor, ELIZA does indeed use personal pronouns; you can see this trait of “her” conversation for yourself.

I “spoke with” ELIZA while preparing this post. Here’s a verbatim transcript of our tête-à-tête, starting with ELIZA’s standard prompt:

ELIZA: Is something troubling you ?

YOU: Not really. You?

ELIZA: Oh, I?

YOU: Yes, you.

ELIZA: I understand.

YOU: Do you really?

ELIZA: You’re not really talking about me—are you?

YOU: No, I actually am.

ELIZA: Are you saying no just to be negative?

YOU: What do you think?

ELIZA: What are your feelings now?

YOU: You tell me.

ELIZA: You like to think I tell you—don’t you?

Granted, I didn’t start my session with ELIZA really intending to bare my soul. So I tried again, a little more earnestly:

ELIZA: Is something troubling you?

YOU: I am upset about Hurricane Sandy.

ELIZA: Do you enjoy being upset about Hurricane Sandy?

At which point, were I on the couch of a real therapist, I’d demand my money back.

Clearly, as that Oxford Dictionaries blog explains, “ELIZA does not pass a Turing test [the barrier which a computer program must break to be considered an artificial intelligence]. If you interact with it the conversation does not last too long before it becomes obvious you are talking to a machine.”

Data is no ELIZA. But if I understand Doug’s comment correctly (and I may not, so please correct me if needed), he is saying either that Picard’s “ultimate argument” isn’t strong enough to distinguish the android from the natural language processor, or that, at best, Picard has only proved that Data presents the appearance of being self-aware.

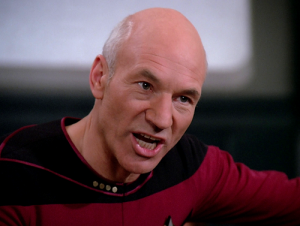

Were the pronoun argument actually Picard’s “ultimate argument,” I’d agree—I wouldn’t want the good captain representing me before Judge Wapner, let alone in a high-stakes court of law! But, as the scene posted above shows, Picard’s argument is multi-faceted, and reaches its crescendo with an appeal to Data’s consciousness—not the mere appearance of consciousness, but the actual presence of consciousness, “in even the smallest degree.” Picard is convinced that Data meets that criterion, leading him to thunder, “Starfleet was founded to seek out new life—well, there it sits!”

How can he be so sure? What makes him so certain?

Personhood in Relationship

Rendering her verdict, Captain Louvois (played by Amanda McBroom) says, “This case has dealt with metaphysics, with questions best left to saints and philosophers.” I might also add theologians, because I think Christian theology offers some guidance as we weigh questions of Data’s identity (and, of course, our own).

All Christian theology properly begins with God; more specifically, with God’s fullest self-revelation in Jesus Christ. Jesus’ first followers were convinced that, when they dealt with Jesus, they were dealing with none other than the God of Israel. Centuries of faithful, prayerful reflection on the biblical confession, “Jesus is Lord,” led the Church to conclude that God is Triune. God is, in God’s very self (in se), a community: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. As the late Shirley C. Guthrie writes, “The oneness of God is not the oneness of a distinct, self-contained individual; it is the unity of a community of persons who love each other and live together in harmony” (Christian Doctrine, rev. ed. [Louisville, KY: Westminster/John Knox Press, 1993], p. 92).

Guthrie continues: “If in God’s own deepest inner being God is such a community-seeking God, then that is also what God is in relation to us” (p. 93). Scripture teaches that God created human beings in God’s own image (Gen. 1.26-27; 5.1). While the imago Dei has been interpreted to mean many things—that we have reasonable intellects, for instance, or the capacity to create—it may mean, bearing God’s Triune nature in mind, that we only “exist,” that we only “have” an identity, in relationship to others. Contrary to the assumptions of modern society—contrary, frankly, to the general assumptions of Star Trek, where community is valued, to be sure, but never at the perceived expense of the sacrosanct individual (this is why the Borg were such baddies, after all)—God, when making us in God’s image, did not make us to be “distinct, self-contained” individuals. Does not God declare, after no helper can be found in the animal kingdom for the first human creature, “It is not good that the man should be alone” (Gen. 2.18)? Borrowing Guthrie’s words again:

If the deity of God is fulfilled in the community of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, then the true humanity of human beings created in the image of God is realized only in human community, not in the lonely self-assertion of individuals who seek to be themselves apart from and against other human beings (pp. 93-94).

In that climactic courtroom scene we watched above, as throughout the episode, much is made of Data’s distinct, individuated self-awareness. As Maddox says of Picard in contrast (so he thinks) to Data: “You are conscious of your existence and actions. You are aware of yourself and your own ego.” But Maddox is confused about the real issue. So is Captain Picard—at least in this scene. From the perspective of Christian theology, Picard made a far stronger case for Data’s sentience, his personhood—dare we even say, his “true humanity”?—when he earlier introduced Data’s personal affection for his crewmates into evidence. In his cross-examination of Data, Picard unpacks what Data had packed when preparing to leave the Enterprise:

PICARD (holding up a book): And this?

DATA: It was a gift from you, sir.

PICARD: You value it?

DATA: Yes, sir.

PICARD: Why?

DATA: It is a reminder of friendship and service.

PICARD (holding up the holographic image of Tasha Yar): And this? You have no portraits of any other of your crewmates. Why this person?

DATA: I would prefer not to answer that question, sir. I gave my word.

PICARD: Mister Data, may I remind you, that you are under oath… And, under the circumstances, I don’t think Tasha would mind.

DATA: She was important to me… we were… intimate.

This scene does far more than redeem one of the most cringe-worthy moments of the first season (no small feat, that). It affirms Data’s personhood because his personhood is established in community. Data is a free individual with the right of self-determination because he has determined to be a member of “a community of persons who love each other and live together in harmony.” He is “community-seeking,” and thus fully congruent with the imago Dei.

This scene does far more than redeem one of the most cringe-worthy moments of the first season (no small feat, that). It affirms Data’s personhood because his personhood is established in community. Data is a free individual with the right of self-determination because he has determined to be a member of “a community of persons who love each other and live together in harmony.” He is “community-seeking,” and thus fully congruent with the imago Dei.

So congruent is Data’s personhood in community, in fact, that, when his story reaches its end in Star Trek: Nemesis, he meets one of the highest definitions of true personhood ever stated, by the fullest human this world has ever known:

“No one has greater love than this, to lay down one’s life for one’s friends” (John 15.13).

Certainly sounds self-aware—and, what’s more, human—to me.

Scripture quotations from the New Revised Standard Version.

My thanks to Scott Gardner and Chris Honeywell, who invited me to discuss this episode (in tandem with the original series’ “Court Martial”) on Episode 270 of their Two True Freaks podcast earlier this year, a conversation that helped me refine my thoughts on this episode.

Next Week: Maybe ELIZA could help Commander Riker with his father issues. Rewatch “The Icarus Factor” and share your thoughts in the comments section!

Excellent!

Well done, and thanks for the acknowledgement. I would only add that the “personal pronoun” argument is, I think, essentially his only *positive* proof, in addition to what Data says about his friends. What *might* be there (a consciousness) is only argued as almost what a defense attorney would call a “reasonable doubt”. Consciousness *might* be there, therefore it should be assumed to be there. That, to me, is a weak case for considering anything “life”; “I might think, therefore, I might be”. Not good enough for conferring all the rights and privileges of a sentient being.

Around this time I was still reading Usenet, and some folks were using the analogy “If it looks like a duck, walks like a duck, and quacks like a duck, it’s a duck.” To which I replied, “Or a mechanical duck.” Simulation of consciousness, as good as it might be, isn’t a replacement for the real thing. Someone like Picard seeking to grant Data rights as a sentient being would not be able to rely on what *might* be there. And thus, his “ultimate argument”, as I put it — the strongest *positive* argument — was how Data spoke.

Thanks for checking back in, Doug! I meant it when I said you raised a good point. It’s a strong objection to the conclusion of the case – is Data a simulation of personhood rather than a person? – and I have no easy answer to it.

In isolation, I think this episode could suggest he’s no more than a simulation. But don’t other episodes establish that he was created with the capacity to grow, learn, evolve, become self-aware and self-determining? If so, then Riker’s statement that Data’s purpose is solely to serve man (if you will!) is only partly true at best, if Dr. Soong’s purpose was for Data to become self-determining. Once we’ve created something that has the capacity to grow, we should let it.

But it’s a fascinating episode because it isn’t clear cut, and I do appreciate your raising the points you have. Please speak up again as we go forward!