I hesitate to say I enjoyed The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey even more than I enjoyed John Carter, only because I know that won’t sound like high praise to most moviegoers. But if you read my rave review of Disney’s unfairly maligned sci-fi epic in this forum, you’ll understand (even if you don’t agree) that I mean the statement as the highest praise.

I hesitate to say I enjoyed The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey even more than I enjoyed John Carter, only because I know that won’t sound like high praise to most moviegoers. But if you read my rave review of Disney’s unfairly maligned sci-fi epic in this forum, you’ll understand (even if you don’t agree) that I mean the statement as the highest praise.

In that post I wrote, “Visually stunning and emotionally stirring, John Carter is a fast-paced and fun adventure that stoked my sense of wonder like no movie has since The Fellowship of the Ring.” Well, with this first installment in his second Tolkien film trilogy, director Peter Jackson has reclaimed top honors in that wonderful world-building matchup. The Hobbit is, at every level, an astonishing achievement—far, far better than I anticipated, and I went into the theater with hopes about as high as a dragon can fly. Jackson and his amazing cast and crew met or, more often, surpassed them all.

“Beautiful Things… Most Marvellous and Magical…”

Those words from Thorin’s description of the dwarves’ handiwork in Tolkien’s original novel can apply equally to the craftsmanship on display in this enthusiastic adaptation of it. Even in “plain old” 2D at 24 frames per second, The Hobbit is beautiful. As many have said, New Zealand itself may be the film’s most special effect; but I enjoyed the computer-generated artistry, too, from such small touches as the blue light of Bilbo’s blade spilling out over the top of its sheath to large-scale accomplishments. The Great Goblin, for instance, at first looks like he should be a comic character, with that huge waddle of his; but the more I watched him, the more “solid” and realistic and menacing he became. The CGI Jabba the Hutt should take lessons from this guy!

One of the most beautiful and marvelous things The Hobbit offers, however, is its script. The screenplay Jackson, Fran Walsh, and Philippa Boyens have written is a delightfully deft and sometimes unexpectedly beautiful retelling of the book’s first six chapters, largely faithful in both broad strokes and fine details, amplified with material from both The Lord of the Rings’ intimidating appendices and the moviemakers’ imaginations. More knowledgeable Tolkien fans than I can sort out exactly which of the storyline’s expansions can claim roots in Tolkien’s text, but I found the film’s narrative coherently arranged and confidently told. Even the initially funny and ultimately poignant side trip to bring in Radagast the Brown felt, in the end, like it had always belonged. I also thought the addition of Azog as a nemesis hot on the dwarves’ heels added a much-needed sense of urgency to this early third of the plot.

One of the most beautiful and marvelous things The Hobbit offers, however, is its script. The screenplay Jackson, Fran Walsh, and Philippa Boyens have written is a delightfully deft and sometimes unexpectedly beautiful retelling of the book’s first six chapters, largely faithful in both broad strokes and fine details, amplified with material from both The Lord of the Rings’ intimidating appendices and the moviemakers’ imaginations. More knowledgeable Tolkien fans than I can sort out exactly which of the storyline’s expansions can claim roots in Tolkien’s text, but I found the film’s narrative coherently arranged and confidently told. Even the initially funny and ultimately poignant side trip to bring in Radagast the Brown felt, in the end, like it had always belonged. I also thought the addition of Azog as a nemesis hot on the dwarves’ heels added a much-needed sense of urgency to this early third of the plot.

Having recently re-read The Hobbit, I noticed other differences, some major (Bilbo did not play the three trolls for time; nor did he know the ring belonged to Gollum when he took it—more on these later), others minor (Gollum “has only six” teeth, not nine). I could quickly and willingly set them all aside, however, in order to enjoy Jackson and company’s version.

“Now We Are All Here!”

I was aided, of course, by the first-rate cast of actors. What more praise can anyone heap on Lord of the Rings alumni Ian McKellen, Hugo Weaving, or (especially) Andy Serkis? (Actually, the Academy should heap an already overdue Oscar on Mr. Serkis.) The “prologue” sequence featuring Ian Holm and Elijah Wood seems, on reflection, largely unnecessary—but, I confess, I was grinning to see those two hobbits on the big screen again, and chuckled heartily as Bilbo accused Lobelia of stealing his best spoons.

I was aided, of course, by the first-rate cast of actors. What more praise can anyone heap on Lord of the Rings alumni Ian McKellen, Hugo Weaving, or (especially) Andy Serkis? (Actually, the Academy should heap an already overdue Oscar on Mr. Serkis.) The “prologue” sequence featuring Ian Holm and Elijah Wood seems, on reflection, largely unnecessary—but, I confess, I was grinning to see those two hobbits on the big screen again, and chuckled heartily as Bilbo accused Lobelia of stealing his best spoons.

New cast members impressed, too. I immediately liked Martin Freeman as Bilbo. He perfectly portrays the “respectable” Mr. Baggins’ development as an adventurer. Nothing he does on screen feels false, from the humor in his front door encounter with Gandalf at the beginning to the compassionate commitment with which he rededicates himself to the dwarves’ quest in the end. I also appreciate the skill with which Freeman and Richard Armitage play Bilbo and Thorin’s relationship. The actors’ obvious emotional investment in their characters’ connection to each other will, I’m sure, make their eventual estrangement over the Arkenstone all the more devastating when we reach the final film.

Armitage makes a very impressive Thorin overall—more impressive than Thorin is in the book! Tolkien writes of a self-important, verbose bore, for whom readers come, as Bilbo does, to have some affection; but who I, at least, could never really picture as “King under the Mountain.” I suppose some fans will be disappointed that this movie reimagines Thorin as a more conventional fantasy hero; and I admit something is lost by making not only Thorin but his kin readier for prime time than they are in Tolkien’s text, as in this choice passage (emphasis added):

Armitage makes a very impressive Thorin overall—more impressive than Thorin is in the book! Tolkien writes of a self-important, verbose bore, for whom readers come, as Bilbo does, to have some affection; but who I, at least, could never really picture as “King under the Mountain.” I suppose some fans will be disappointed that this movie reimagines Thorin as a more conventional fantasy hero; and I admit something is lost by making not only Thorin but his kin readier for prime time than they are in Tolkien’s text, as in this choice passage (emphasis added):

There it is: dwarves are not heroes, but calculating folk with a great idea of the value of money; some are tricky and treacherous and pretty bad lots; some are not, but are decent enough people like Thorin and Company, if you don’t expect too much (Chap. XII).

On the other hand, “not-heroes” who are “decent enough” “if you don’t expect too much” might not make a direct translation to the screen too well, and viewers whose only previous exposure to Tolkien’s dwarves was John Rhys Davies’ Gimli might well have come to The Hobbit expecting at least a little more. So I welcome Armitage’s Thorin Oakenshield. He convinces me, as he did Dwalin Balin (a kind old soul very winningly played by Graham McTavish Ken Stott), that he is a king worthy of loyal, life-long service.

I do think the character of Bilbo grows too quickly in this first film. In the book, Gandalf basically shoves Bilbo out the door: Bilbo doesn’t wake up and boldly decide to sign the contract. His attempt to pick the trolls’ pockets is a disaster. (Well, to pick their talking purse, an element I’d hoped might make it onscreen, Cockney accent and all—I mean, if that goofy joke about the invention of golf survived to the final draft, surely the trolls’ talking purse should have!) He does not know anyone has a claim to the ring when he picks it up beneath the Misty Mountains—as the movie stands, Bilbo really does seem the outright thief Gollum accuses him of being, and the final “riddle” seems more of a taunt than an honest misstatement of which Bilbo then avails himself. And Bilbo certainly doesn’t leap out of a flaming fir tree to defend Thorin at risk of his own life and limb. (In fairness, neither he nor anyone else has to in the book, since Thorin stays up the trees with everyone else until the Eagles’ timely arrival.) As any reader of The Hobbit knows, much adventure lies ahead of Mr. Baggins at this point; yet, by the close of An Unexpected Journey, he seems more than ready to face whatever his path through the Wild and to the Lonely Mountain may throw at him. I fear it will be hard even for Freeman to sell me on the fact that Bilbo’s decision to enter Smaug’s lair rather than turn back was “the bravest thing he ever did,” as Tolkien asserts. Movie Bilbo has already thrown himself out of a tree directly at a snarling goblin, for goodness’ sake! One lesson I learned in my brief, high school acting career was: you must always leave room for your character to build. Through no fault of Freeman’s—he didn’t plot the story beats, after all—Bilbo emerges from these three hours as every inch a clever, daring, fearless hero. How will he win even further admiration from the dwarves through his scheme to escape the wood elves’ dungeons? How will he win even further admiration from us when he faces down Smaug? (Although I can’t wait until he does: Watson vs. Sherlock!)

I do think the character of Bilbo grows too quickly in this first film. In the book, Gandalf basically shoves Bilbo out the door: Bilbo doesn’t wake up and boldly decide to sign the contract. His attempt to pick the trolls’ pockets is a disaster. (Well, to pick their talking purse, an element I’d hoped might make it onscreen, Cockney accent and all—I mean, if that goofy joke about the invention of golf survived to the final draft, surely the trolls’ talking purse should have!) He does not know anyone has a claim to the ring when he picks it up beneath the Misty Mountains—as the movie stands, Bilbo really does seem the outright thief Gollum accuses him of being, and the final “riddle” seems more of a taunt than an honest misstatement of which Bilbo then avails himself. And Bilbo certainly doesn’t leap out of a flaming fir tree to defend Thorin at risk of his own life and limb. (In fairness, neither he nor anyone else has to in the book, since Thorin stays up the trees with everyone else until the Eagles’ timely arrival.) As any reader of The Hobbit knows, much adventure lies ahead of Mr. Baggins at this point; yet, by the close of An Unexpected Journey, he seems more than ready to face whatever his path through the Wild and to the Lonely Mountain may throw at him. I fear it will be hard even for Freeman to sell me on the fact that Bilbo’s decision to enter Smaug’s lair rather than turn back was “the bravest thing he ever did,” as Tolkien asserts. Movie Bilbo has already thrown himself out of a tree directly at a snarling goblin, for goodness’ sake! One lesson I learned in my brief, high school acting career was: you must always leave room for your character to build. Through no fault of Freeman’s—he didn’t plot the story beats, after all—Bilbo emerges from these three hours as every inch a clever, daring, fearless hero. How will he win even further admiration from the dwarves through his scheme to escape the wood elves’ dungeons? How will he win even further admiration from us when he faces down Smaug? (Although I can’t wait until he does: Watson vs. Sherlock!)

Home Again, Home Again…

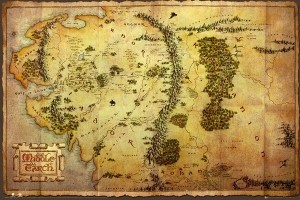

Thinking once more about my experience of John Carter: I told SFC readers I felt “at home” on Barsoom. So not surprisingly, I felt very at home in Middle Earth. Tolkien’s just about perfect “sub-creation” comes to vivid life in Jackson’s very nearly perfect “sub-sub-creation!” We saw once more The Shire, Rivendell, and the Mines of Moria; we watched Gandalf knock his head against the chandelier in Bag End’s entrance hall—the first time for him, the second time for us; we heard Gollum arguing with his inner Sméagol again (the brilliance of that onscreen riddle game onscreen, albeit abbreviated and with Bilbo’s ring-snatching more morally ambivalent than even Tolkien revised it, can’t be overemphasized; it’s the movie’s dramatic standout sequence)—and all of it set to a lush, immersive Howard Shore score that effortlessly moves between leitmotivs from The Lord of the Rings and new thematic material, especially the dwarves’ lament for their long-forgotten gold, far o’er the Misty Mountains cold…

Thinking once more about my experience of John Carter: I told SFC readers I felt “at home” on Barsoom. So not surprisingly, I felt very at home in Middle Earth. Tolkien’s just about perfect “sub-creation” comes to vivid life in Jackson’s very nearly perfect “sub-sub-creation!” We saw once more The Shire, Rivendell, and the Mines of Moria; we watched Gandalf knock his head against the chandelier in Bag End’s entrance hall—the first time for him, the second time for us; we heard Gollum arguing with his inner Sméagol again (the brilliance of that onscreen riddle game onscreen, albeit abbreviated and with Bilbo’s ring-snatching more morally ambivalent than even Tolkien revised it, can’t be overemphasized; it’s the movie’s dramatic standout sequence)—and all of it set to a lush, immersive Howard Shore score that effortlessly moves between leitmotivs from The Lord of the Rings and new thematic material, especially the dwarves’ lament for their long-forgotten gold, far o’er the Misty Mountains cold…

As Sam Gamgee said at the end of The Lord of the Rings, audiences who loved Jackson’s trilogy a decade ago can say of The Hobbit, “Well, I’m back.”

And sci-fi- and fantasy-minded Christians can say, as they could of John Carter, that we can experience a homecoming even more fantastic through Jesus Christ.

Tolkien’s fellow Inkling C.S. Lewis spoke of Sehnsucht—“the haunting longing,” writes Terry Lindvall, “that touched Lewis throughout his life, that full, heavy, enveloping nostalgia for a fulfillment that awaited him—in something, somewhere.” Professor Michael Drout, in his audio lecture series Of Sorcerers and Men, points to a similar longing in Tolkien’s works: “The loss of his mother and of his happy life in the English countryside seems to have generated a strong nostalgia in Tolkien… Tolkien made nostalgia… a central emotional driver of his mythology” (course guide, p. 16).

An Unexpected Journey highlights, even intensifies, the dwarves’ “nostalgia” or Sehnsucht. They speak and sing of the glories of their past, as they do in the text; but the film gives us viewers the chance to see that glorious past for ourselves, independent of the dwarves’ recollection of it. We can empathize with their yearning to reclaim and restore what was once theirs. We may even remember expressions of such longing from Scripture:

By the rivers of Babylon—there we sat down and there we wept when we remembered Zion… If I forget you, O Jerusalem, let my right hand wither! Let my tongue cling to the roof of my mouth, if I do not remember you, if I do not set Jerusalem above my highest joy (Ps. 137.1, 4-6).

But as God’s chosen people discovered after the Babylonian Exile, even a homecoming cannot be (to borrow Tolkien’s penchant for capitalizing nouns in The Hobbit) The Homecoming.

As the dwarves will learn before the Third Age of Middle Earth draws to its close, even the restoration of the great kingdoms of Erebor and Moria will not last.

As we Christians discover whenever we pine for the past—perhaps our own, personal pasts, when we were (or think we were) happier; perhaps the past of the church, when newspapers published Sunday sermons and public schools sanctioned prayer and our denominations and congregations enjoyed the automatically granted, Baggins-esque respectability only possible when western “Christendom” held sway—we can’t go back.

We are so often like Elijah (the prophet—not Mr. Wood!), as he fled for his life from Queen Jezebel. Desperate and despairing, he had no better plan than to run back to “Horeb the mount of God” (1 Kings 19.8), retracing the Israelites’ steps to the lonely mountain on which God descended in fire to give God’s holy nation the Torah. But while Elijah finds at Horeb (also called Sinai) earthquake, wind, and fire—all the old trappings of God’s appearing—he does not find God. God has moved on, into the future, and calls and strengthens Elijah to follow.

Tolkien and Lewis both knew that the past is not our home. The future is our home, and our future is with God, who will, when the heavenly city at last descends, make his home with humanity, even as he has already bound himself to us in Jesus (Rev. 21.2-3;  John 1.14).

John 1.14).

Bilbo’s homesickness for Bag End is transformed in the film (and thus redeemed) from mere nostalgia to holy nostalgia, for it drives him forward, moving him to help the dwarves regain their home, however he can. May whatever nostalgia we feel, whenever we feel it, also be transformed, by God’s Spirit, into Sehnsucht, the haunting, holy longing that drives us forward, into the future, following the One who always goes before us, so that where he is, we may be also (John 14.3).

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version.

One comment on ““The Hobbit:” One Sci-Fi Christian’s Review (with spoilers)”