I have been a fairly outspoken supporter of Andrew Stantons’ 2012 John Carter. The marketing campaign stole some of my excitement before I saw the film, but the finished product pushed itself into my top five movies of 2012. I am someone who would love a sequel and further exploration of Barsoom. And it is because of the movie that I picked up the original A Princess of Mars by Edgar Rice Burroughs and found myself entranced by a really well developed world in the midst of romantic adventure. I would say due to the film, I am a new convert to Barsoom, and I think there are others like me.

I have been a fairly outspoken supporter of Andrew Stantons’ 2012 John Carter. The marketing campaign stole some of my excitement before I saw the film, but the finished product pushed itself into my top five movies of 2012. I am someone who would love a sequel and further exploration of Barsoom. And it is because of the movie that I picked up the original A Princess of Mars by Edgar Rice Burroughs and found myself entranced by a really well developed world in the midst of romantic adventure. I would say due to the film, I am a new convert to Barsoom, and I think there are others like me.

Michael D. Sellers however is part of the pre-movie fan base. For Sellers, awaiting John Carter, was a dream come true where his beloved franchise would finally get its proper due on the big screen. Sellers may have found the final product on the screen satisfactory, but the support given it by Disney was a clear disappointment. For a movie that was budgeted to be a tentpole movie for Disney, the movie was never given the support its $250 million budget should have warranted. The fact that this blockbuster in waiting became either invisible or misunderstood by the potential audience largely led to the label as Disney’s Ishtar.

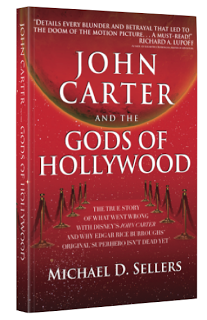

Sellers in John Carter and the Gods of Hollywood examines the historical development of the film from the Edgar Rice Boroughs decision to write his first short story to the home video release of John Carter. He examines the multiple attempts to bring Barsoom, or Mars, to the big screen including failed efforts by Disney and Paramount. With the Pixar acquisition of Disney just finalized and the John Carter rights being released from Paramount, Carter fan and director Andrew Stanton suggested that Disney studio head Dick Cook pursue the franchise. Cook wishing to please a key member of the Pixar team and a proven director agreed to purchase the rights, despite an earlier Disney failed attempt to develop a Carter film. Stanton, who became a John Carter fan through the 1970s Marvel comics, diligently worked with fellow Carter fans and a supportive producing staff to bring the century old story to a modern audience while staying under the enormous budget. But with the replacement of Cook by Rich Ross, the corporate enthusiasm for Stanton’s first live action release ended. Ross would never give his full support to this project green lighted under the old regime. Ross’ newly hired marketing head, MT Carney, a new voice in movie marketing, was focused on a backlog of projects releasing before John Carter and departmental reorganization. These priorities were placed before the marketing of the potential tentpole film. Additionally, Carney’s research led Disney to remove the phrase “of Mars”, a change that generally meant much of the potential audience was not aware the film was a science-fiction offering. And Disney CEO Bob Iger, while not actively sabotaging the film was interested in acquiring LucasFilm, a desire which could have been hindered by a successful film. The lack of enthusiasm, and marketing, lead the movie to underperformed and be labeled a failure by Disney within ten days of release and before entering the world’s two largest film markets (China and Japan). Sellers finishes his story by discussing a real win for John Carter, being ranked number one in DVD sales upon release. He closes by discussing the possibility of future Carter movies and the circumstances under which a sequel could be made. And Sellers reviews the various personalities in the real life story of John Carter’s failure and identifies their role in the movie’s bust label.

John Carter and the Gods of Hollywood is probably one of the best corporate history titles I have read since Disney War. Sellers does an excellent of job of trying to understand the politics of Disney and why decisions were made. And I think it is fair. For example, as a hardcore Burroughs fan it would be easy for him to paint a picture of Carney that is, well, evil. Many have lambasted her efforts in marketing the film including the decision to remove “of Mars”. Instead Sellers attempts to paint a picture where readers can understand what Carney had to overcome and the competing priorities of her short lived Disney posting. One can understand the pressures and blind spots that Carney was not able to overcome. Still he is honest in showing how the social media campaign failed, and was lacking, for this expert in new media. Additionally, he could have painted Iger as a villain killing the Carter film. Instead, Sellers explains Iger’s acquisition strategy, making it clear why he may have lacked excitement for a film that could have hindered his ability to bring Star Wars fully into the Disney family. Additionally, Sellers deeply analyses the Disney marketing strategy for the film including its poor poor results, especially when compared to The Avengers and The Hunger Games.

Sellers as an author is not just analyzing this story but is also part of it. Sellers was a proactive member of the Burroughs fan community who attempted to move the needle in support of the film. He discusses how he built the fan site www.thejohncarterfiles.com and edited his own fan trailer, one that Andrew Stanton declared was the only trailer that got the movie. Sellers is realistic about the obstacles that a John Carter film had to overcome and looked to the fan community to help Disney overcome them. For example, the number of Burroughs fans had declined severally and the Barsoom stories were a century old. So it did not have an active fan base as vocal as more recent The Hunger Games to bolster the film and other films such as Star Wars and Avatar had strip-mined the film of key story elements. Sellers as a character in the book had sought to convince Disney and the fan base that the fan community should be actively seeking new members and explaining that John Carter was the inspiration for many popular movies, not a cheap carbon copy of them. Sellers’ attempts were not supported on many sides. While Stanton may have supported his fan trailer, Disney was not interested in seeking inroads with fans. And even the fan community spoke with negative voices expressing concerns about Stanton’s movie and story changes. Some did not see as Sellers predicted that the movie could bring new fans to the Burroughs’ library, like myself.

John Carter and the Gods of Hollywood is a fair, factual and enlightening assessment of what went wrong with the development, marketing and release of John Carter. The book is well written and clear, and has a personal touch as Sellers enters the story describing his own efforts to support a movie sight unseen. Sellers closes with the belief that there could still be life in the Carter franchise, just not with Disney, and for fellow Carter fans I hope he is right. John Carter and the Gods of Hollywood is a tragedy, showing us the blockbuster that could have been and how the efforts, or lack of, made it one of the most ridiculed movies of 2012.

Review Copy Provided by Author

Orginally Posted at www.betweendisney.com

I loved the movie, and never understood why it was called a flop. In what way?

When you added the film’s budget to the marketing costs, Disney determined it was a financial flop where they would be takign a loss.

Of course that decision was made before the film entered two of the largest markets in the world. And taking the long view, it was also before DVD sales. And knowing Disney I am sure they will find ways to continue to recoup, cough cough, thier loses.