I didn’t read Super Boys. I devoured it.

I didn’t read Super Boys. I devoured it.

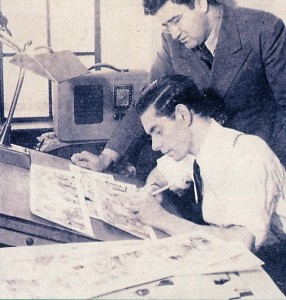

I tore through Brad Ricca’s engrossing new biography of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, the co-creators of Superman, as though I’d never read anything about these two Cleveland teens’ persevering quest to break into comics; their inspired imagining of a character who became one of a handful of true American fictional icons; or their life-long struggles for critical acceptance, just compensation, and public recognition. Their story, in its broad outline, is by now familiar to many, certainly to most superhero fans and to students of popular culture. Ricca, however, tells their tale so skillfully and passionately, you’ll finish the book wondering, as I did, “Why didn’t I know any of this before?”

Ricca is a gifted wordsmith, and he recounts Siegel and Shuster’s history in novelistic fashion. As much as I’m excited to see Man of Steel this weekend, I’d certainly also buy a ticket to see Super Boys on the big screen. Read Ricca’s description of a young Shuster sweating his way through an art class assignment, for example; or of the fateful night the future Joanne Siegel, then an aspiring model, posed as the model for Lois Lane; or of “Superman Day” at the 1939 World’s Fair; and you’ll hear Ricca’s text crying out to be filmed. Ricca’s work as a poet serves him well in these pages as, scene after vivid scene, he makes the past present for his readers.

Super Boys is more than style, however. It boasts plenty of substance. Ricca has done exhaustive homework. He provides a wealth of new information (all expertly documented in his end notes, which, I promise, are fascinating reading in and of themselves–see the note about Superman’s “S”-shield as a case in point) and illuminates many of this story’s overlooked facets along the way. One of the chapters I found most interesting was Ricca’s survey of Siegel’s Army service as a columnist for Stars and Stripes during World War II. Ricca weaves excerpts from Siegel’s “Take a Break” column into his narrative, including some of Siegel’s contribution to the saga of the ubiquitous “Kilroy Was Here” graffiti, showing how Siegel’s wartime work sheds light on him as both a cartoonist and a man. I was also intrigued by the brief appearance in real life of one of Siegel’s favorite pseudonyms (you’ll have to read Chapter 22 for yourself to believe it), and by Ricca’s exegesis of Siegel’s later inversion of the Superman mythos, The Starling.

Super Boys has some flaws—none so deadly as kryptonite is to Superman, but imperfections all the same. It seems, at times, like a hagiography of Shuster: while it presents Siegel as fully human, faults and all, Shuster emerges as unerringly patient, long-suffering, and misunderstood. Understand, I have no reason to doubt he was any of these things; perhaps no one has anything negative to say about the man; but the way in which Ricca touches only briefly on Shuster’s late-in-life failed marriage, combined with what I perceived as a lack of critical attention to him throughout the book, struck me as curious. I also think Chapter 27, which contains Ricca’s earnest effort to psychoanalyze Siegel through the first Superman newspaper strip, works a bit too hard to be persuasive.

Overall, however, Super Boys should be at the top of your summer reading list. Even if you are not a Superman fan, it is a riveting story of creativity in action—a testament to the role of both luck and labor, and to the importance of having both a compelling vision and the persistence to realize it, not once and for all, but repeatedly.

Overall, however, Super Boys should be at the top of your summer reading list. Even if you are not a Superman fan, it is a riveting story of creativity in action—a testament to the role of both luck and labor, and to the importance of having both a compelling vision and the persistence to realize it, not once and for all, but repeatedly.

In one of his last interviews, Shuster reflected, “There aren’t many people who can honestly say they’ll be leaving behind something as important as Superman. But Jerry and I can, and that’s a good feeling.” None of us can plan, of course, on leaving behind that kind of legacy—but, having experienced Super Boys, I certainly want to try.

2 comments on “Book Review: “Super Boys” by Brad Ricca”