My mother was the first person to tell me about Battlestar Galactica. “You’d probably enjoy that,” she said, pointing to the ad in the newspaper’s TV listings for September 17, 1978. “It looks like it’ll be a lot like Star Wars.”

My mother was the first person to tell me about Battlestar Galactica. “You’d probably enjoy that,” she said, pointing to the ad in the newspaper’s TV listings for September 17, 1978. “It looks like it’ll be a lot like Star Wars.”

Mom was right on both counts. And while Battlestar’s visual and thematic similarity to Star Wars is what defines (and damns) it for many viewers now, those qualities made it as welcome to this Star Wars-starved six-year-old then as fresh tylium to a fuel-depleted Colonial Viper.

Battlestar was part of my childhood—only briefly, but long enough for me to have strong memories of poring over its picture storybook as though it were The Book of the Word, scrawling multiple sketches of its characters and ships (some of which are reproduced in this post for your entertainment, no extra charge), and pretending during nighttime car rides that I held a Viper control stick in my right hand, and that the headlights of oncoming traffic were Cylon Raiders closing in for the kill. Engage turbo engines! Fire laser cannons!

Battlestar was part of my childhood—only briefly, but long enough for me to have strong memories of poring over its picture storybook as though it were The Book of the Word, scrawling multiple sketches of its characters and ships (some of which are reproduced in this post for your entertainment, no extra charge), and pretending during nighttime car rides that I held a Viper control stick in my right hand, and that the headlights of oncoming traffic were Cylon Raiders closing in for the kill. Engage turbo engines! Fire laser cannons!

As quickly as Battlestar came, it went. I watched the short-lived (rightly so) follow-up series Galactica 1980 a few times and, though I thought the Colonials’ flying motorcycles were cool, the arrival of The Empire Strikes Back that same year reclaimed the primacy of George Lucas’ galaxy in my imagination. Larson’s rag-tag fleet could no longer compete.

I caught a few old episodes on the Sci-Fi Channel in the late 90s, but not even Ron Moore’s reimagining of the property prompted me to revisit it. Recently, however, I started wondering whether the original show could hold any value for me beyond the sentimental. Could I watch “Galactica 1.0” and find reason to appreciate it on its own merits?

Armed with DVDs of the three-episode pilot movie, “Saga of a Star World,” and a few early episodes, as well as with an open mind, I decided to find out.

Battlestar Wars?

The show still reminds me of Star Wars, of course. Even the stylized font of its opening credits evokes the Star Wars logo. Composer Stu Phillips deserves kudos, however, for writing a main theme that does more than ape John Williams’ work. While equally big and brassy, Phillips’ music breathes with a sweeping sense of longing all its own, and entirely appropriate to the series’ subject matter.

Generally speaking, Battlestar still looks remarkably good. The title vehicle is an impressive, fairly

Generally speaking, Battlestar still looks remarkably good. The title vehicle is an impressive, fairly

plausible aircraft carrier in space. The Cylon centurions were no doubt meant to mimic Star Wars’ stormtroopers, but emerge as more interesting. The little red light that runs along their eyeslits has always fascinated me, and their heavily synthesized voices truly are the sound of humanity’s worst fears about technology, almost as creepy, even now, as the voice of the Borg Collective.

Not every aspect of the special effects holds up. For example, one alien race from “Saga,” the Ovions, cut a ridiculous figure, looking like they have just wandered in as refugees from a Doctor Who story across the pond with an especially paltry budget. But legendary special effects wizard John Dykstra, who worked on Star Wars as well as Battlestar, gave television audiences something that resembled that blockbuster movie more than anything yet seen on the small screen. Today, when we watch computer-generated cosmic spectacle on a regular basis, it’s easy to scoff at Battlestar’s relatively simple and frequently repeated effects shots. In 1978, however, these scenes marked a new level of technical expertise for weekly TV.

Besides, I still think the models of the Vipers and the Raiders are elegant. They seem to be speeding forward even when at rest. I never owned, and never really wanted, a toy TIE fighter, but I desperately wanted (and even now wouldn’t mind having) a Cylon Raider.

Considering the Cast

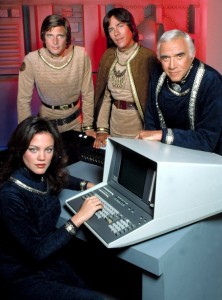

People also often criticize Battlestar’s acting. It is hard to pretend any of the cast turns in a truly remarkable performance. As that painfully earnest paragon of virtue, Captain Apollo—all the fresh-faced optimism of Luke Skywalker, saddled with the almost sanctimonious moral certainty of early-TNG Wesley Crusher—Richard Hatch is generally uninspiring. He does manage a few genuinely warm moments with Jane Seymour’s not-long-for-this-series Serina and his soon-to-be adopted son Boxey, played by Noah Hathaway (better known as Atreyu in The NeverEnding Story, now busy designing and riding custom motorcycles—no word on flying ones), but Hatch doesn’t create an Apollo who can be both heroic and human. Watch “The Lost Warrior,” a misguided homage to the spaghetti western tradition (complete with Cylon gunslinger) to catch Apollo at his better-than-anyone best. Even in that episode, however, Hatch delivers a “moral of the week” line about killing with surprising authenticity. Flashes of the fine actor he’d become by the time of the BSG reboot do show through from time to time.

People also often criticize Battlestar’s acting. It is hard to pretend any of the cast turns in a truly remarkable performance. As that painfully earnest paragon of virtue, Captain Apollo—all the fresh-faced optimism of Luke Skywalker, saddled with the almost sanctimonious moral certainty of early-TNG Wesley Crusher—Richard Hatch is generally uninspiring. He does manage a few genuinely warm moments with Jane Seymour’s not-long-for-this-series Serina and his soon-to-be adopted son Boxey, played by Noah Hathaway (better known as Atreyu in The NeverEnding Story, now busy designing and riding custom motorcycles—no word on flying ones), but Hatch doesn’t create an Apollo who can be both heroic and human. Watch “The Lost Warrior,” a misguided homage to the spaghetti western tradition (complete with Cylon gunslinger) to catch Apollo at his better-than-anyone best. Even in that episode, however, Hatch delivers a “moral of the week” line about killing with surprising authenticity. Flashes of the fine actor he’d become by the time of the BSG reboot do show through from time to time.

Early on, Dirk Benedict shows more emotional range as hotshot pilot Starbuck than I’d remembered. His already rocky relationship with Commander Adama’s daughter Athena (Maren Jensen) suffers further stress in the wake of the colonies’ destruction. But the script doesn’t allow Benedict too much time to explore these tentative hints of insecurity and vulnerability. He’s mostly the cigar-chomping, lady-loving, wisecracking card shark I recalled—Han Solo’s preppie cousin.

I’ll admit that, had I been a few years older at the time, I would have had a big crush on the beautiful Ms. Jensen, a model who was making the move into acting. Like most of the cast, she gives the scripts her best shot, but that’s an often thankless task. “Whatever happened to the joy of living to fight another day?” Athena asks her father at one point—an astonishingly inappropriate question considering most of the human race has been annihilated only days earlier.

Among the other supporting players, Herbert Jefferson, Jr. makes the most of meager script material as level-headed, likeable Boomer. For instance, his and his fellow pilots’ attempts to throw Apollo a bachelor party while avoiding Colonel Tigh’s watchful eye in “Lost Planet of the Gods” are pretty endearing. Boomer’s the ideal big brother: level-headed and in control during a crisis, but able to loosen up and laugh with you in good times. And I’d be remiss if I didn’t praise John Colicos for chewing the scenery with every ounce of over-the-top villainy he can muster. His Baltar is a campy cartoon villain, no question. No moral ambiguity here—“I’ll get you! You haven’t heard the last of Baltar!” he shouts from beneath the ruins of a temple on Kobol—but, frack, is he fun to watch!

Among the other supporting players, Herbert Jefferson, Jr. makes the most of meager script material as level-headed, likeable Boomer. For instance, his and his fellow pilots’ attempts to throw Apollo a bachelor party while avoiding Colonel Tigh’s watchful eye in “Lost Planet of the Gods” are pretty endearing. Boomer’s the ideal big brother: level-headed and in control during a crisis, but able to loosen up and laugh with you in good times. And I’d be remiss if I didn’t praise John Colicos for chewing the scenery with every ounce of over-the-top villainy he can muster. His Baltar is a campy cartoon villain, no question. No moral ambiguity here—“I’ll get you! You haven’t heard the last of Baltar!” he shouts from beneath the ruins of a temple on Kobol—but, frack, is he fun to watch!

As the Galactica paterfamilias, Lorne Greene brings a gentle gravitas to the role of Adama. I enjoy him most in his grandfatherly moments—telling Boxey bedtime stories about Earth, for example, in “The Lost Warrior”—but he is on occasion also capable of tapping into the trauma his character has just lived through to powerful effect. Watch him admit to Athena in “Saga” that the burden of leadership is weighing heavy on him. “You didn’t see them down there,” he tells her, speaking of survivors on Caprica’s surface, “their faces—the old, the young—desperate, begging, screaming for a chance to come aboard—a chance to live—and there I was like God, passing out priorities as if they were tickets to a lottery.” This glimpse of Adama’s private pain (which Greene played with even more raw emotion in an unused take, preserved in the DVD’s selection of deleted scenes) adds texture to his public persona as the confident, decisive commander of the fleet. Had scriptwriters taken more seriously the implications of their premise, Greene and the rest of the cast would have had more resources with which to create consistently emotionally resonant characters.

As the Galactica paterfamilias, Lorne Greene brings a gentle gravitas to the role of Adama. I enjoy him most in his grandfatherly moments—telling Boxey bedtime stories about Earth, for example, in “The Lost Warrior”—but he is on occasion also capable of tapping into the trauma his character has just lived through to powerful effect. Watch him admit to Athena in “Saga” that the burden of leadership is weighing heavy on him. “You didn’t see them down there,” he tells her, speaking of survivors on Caprica’s surface, “their faces—the old, the young—desperate, begging, screaming for a chance to come aboard—a chance to live—and there I was like God, passing out priorities as if they were tickets to a lottery.” This glimpse of Adama’s private pain (which Greene played with even more raw emotion in an unused take, preserved in the DVD’s selection of deleted scenes) adds texture to his public persona as the confident, decisive commander of the fleet. Had scriptwriters taken more seriously the implications of their premise, Greene and the rest of the cast would have had more resources with which to create consistently emotionally resonant characters.

Tomorrow, Part Two will consider some of Battlestar’s themes and spiritual applications as potential sources of its staying power.

I was all about “Battlestar Galactica” reruns on the Sci-Fi Channel in the 90s. I never really made any comparisons between it and Star Wars, though, probably because I was still three years away from being born in 1978.

I liked your analysis of Apollo’s character, that he was as much a moral paragon as Baltar was a cartoonish villain. There weren’t any layers in their characters: good was good and bad was bad. I don’t know if that’s a result of the time it was produced or if the producers were attempting to replicate the Good vs. Evil of Star Wars.

I loved the reimagined BSG because of its multi-layered characters. Baltar wasn’t a cartoon villain, Apollo often didn’t know right from wrong and everyone else had some evil mixed in with their good, or vice versa. The added ambiguity probably says a lot about how our culture changed from 1978 to 2004 and it also made for more interesting television.

You will get no argument from me, Scott, that TV in general had less tolerance for complex characters, let alone morally ambiguous ones, in 1978 than it does today. Tomorrow, in Part 2, I’ll touch on what I think the original series did right. Characterization wasn’t its greatest strength (although it wasn’t completely devoid of them, either), but there’s lots of thematic potential from the get-go, and it’s developed more fully than I had remembered. But that’s all for tomorrow! Thanks for reading and for the comment!

I watched Battlestar when it aired also and loved it. I was so upset to see it go. I had all the toys and would often run around with my viper after a cylon. My family and me even made some home movies using the toys. Ahhh the memories.

I did watch the entire run of Ron Moore’s BSG and found it an interesting take on the old show and even enjoyed it until the final episode. I believe he had a great opportunity and threw it out the window like a child having a temper tantrum because the show didn’t get the two year renewal he wanted. In fact, he has even said as much when he states that they had a completely different final worked out and then he walked into the writers room and threw that all out for the ending we have.

I would have loved to seen an updated version of the ship of lights show up to explain Starbuck and help resolve the cylon issue and wrap everything up in a cool neat package. But that was not to be.

Back to the 1978 BSG, still love it today even though it is dated. I would love to see a reboot of this show done right. I think it would be awesome TV. Even RMBSG was a ratings hit.

Thanks for reading and commenting, Patrick. Nice to share the nostalgia with someone! I agree with you about the ending of Moore’s BSG, although it lost most of its luster for me mid-way through season 3. After that point, it felt like it had gone completely off the rails and wasn’t even trying to make sense any more. I’m all for sense of wonder and spirituality in science fiction, but not at the expense of reason – not as a “who knows?” kind of “resolution” to a story.

Oh, well. This week is about remembering and celebrating the original, so be sure to come back for Part 2 tomorrow!

I was also disappointed at points but I guess I held on because I naively thought that when it was done I would have that satisfying feeling that the show was worth it. And I didn’t. I liked the updated Cylons but their supposed “plan” that was touted in seasons 1 and 2 disappeared in the later half of season 3 and in season 4. I am not sure if they abandoned the first plan because of the way they wrote themselves into a corner about the final five cylons or did they not have one and were just shooting from the hip.

But as much as I did enjoy parts of RDM’s BSG, he did miss the overall point. The original BSG was really about family. Adama and his son, Apollo, and daughter, Athena and grandson, Boxey. Starbuck was like the kid next door whose parents were absent and he was basically adopted into the family. The rest Tigh, Boomer, Jolly, etc were all neighborhood families that interacted at the giant pool together and played together. Then when suddenly their happy little house on the praire town/block were threatened, pulled in together to stand with one another to fight for a future. That was totally missing in RDM’s BSG. Yes, there was some of it but it was small and even played down. And with Starbuck now Apollo’s love interest, you lost a lot of the family bond in favor of sexual tension. And while sex can sell, family lasts longer. I think that is why the original BSG still has a following. And why Firefly has such a following because those nine characters (ten if you count the ship) were a motley kind of family.

Anyway, just my thoughts 🙂

I think you hit the nail on the head, P.R. I was going to say more about this difference between the two series, but ultimately decided against it; however, I do feel RDM’S BSG, for all its many strengths, does not do justice to this community theme (or family, as you very aptly put it) in the way that old BSG, for all its weaknesses, does. Yes, I can think of some instances where it is there – the pilot miniseries, certainly, and episodes like “33” (Lee’s agony over whether or not to fire on the Olympic Carrier comes down to the fact that he’s being asked to take out a part of the fleet community/family), and things like the running tally on Roslin’s white board — but, overall, BSG is all about the fascinating individual characters. And they are fascinating, in a way that I can’t honestly say the original characters were… but, yes, the originals were a family, and mostly functional.

I wish I could get into Firefly the way so many others have. I bear it no ill will; it just has never really captured me. Maybe I’ll give it a third try in the not too distant future (after I finish rewatching original BSG).

Thanks, as ever, for joining the discussion!