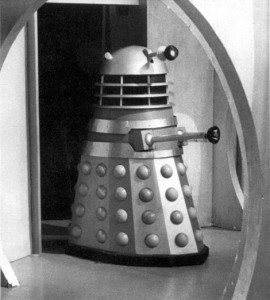

Even people who’ve never watched Doctor Who stand a fair chance of recognizing at least one of three iconic elements from the show: the TARDIS, Tom Baker’s scarf, and the villains of the show’s second serial, which premiered fifty years ago this weekend, “The Daleks” by Terry Nation.

Even people who’ve never watched Doctor Who stand a fair chance of recognizing at least one of three iconic elements from the show: the TARDIS, Tom Baker’s scarf, and the villains of the show’s second serial, which premiered fifty years ago this weekend, “The Daleks” by Terry Nation.

In one of many delightful moments in the recent docudrama An Adventure in Space and Time, producer Verity Lambert realizes Doctor Who is a hit when she sees young children chasing each other while shouting, “Exterminate! Exterminate!” While the verb in its imperative form wasn’t yet the metal-cased menaces’ battle cry by early 1964, the scene is essentially authentic. The Daleks proved an immediate sensation. Between episode two of this serial, when Daleks fully appeared on screen for the first time, and episode three, the size of the viewing audience jumped from 6.4 million to 8.9 million; the final two installments attracted 10.4 million viewers each. In violating the BBC’s initial ban on “bug-eyed aliens” in the program, the Daleks ensconced both the show and themselves in British and world popular culture.

Sympathy for the Daleks?

In other stories, Doctor Who revisits and revises the neutron war that devastated the planet Skaro. This story itself, however, invites audiences to count the cost of war by hinting that there is blame enough for the catastrophe to share.

In other stories, Doctor Who revisits and revises the neutron war that devastated the planet Skaro. This story itself, however, invites audiences to count the cost of war by hinting that there is blame enough for the catastrophe to share.

There’s no doubt the Daleks are the villains of the piece. The Doctor, Ian, Barbara, and Susan wonder for a while about their captors’ intent. In fact, even after several viewings, I’m unclear how our heroes realize the Daleks are setting a trap for Temmosus—perhaps they simply intuit the danger? I also don’t know why Ian waits so long to shout a warning to the targeted Thal chieftain; or how he concludes that irrational xenophobia—“dislike of the unlike”—drives the Daleks. (Later stories will establish that Ian’s right, but he has no empirical evidence for the claim by the point he makes it.)

We, however, are privy from the beginning to the Daleks’ nefarious plotting to claim the planet for themselves. We are not surprised when they lift their eyestalks and plungers and shout, with Sieg Heil-esque intensity, “Tomorrow we will be masters of the planet Skaro!”

The story in no way countenances the Daleks’ “senseless, evil murder,” as the Doctor rightly calls it; but it does leave room to wonder why they act as they do. Again, set aside all you know about the Daleks from the next forty-nine years. In this serial, we know only that, centuries earlier, the Thals were the fierce warriors, while the Daleks were scientists and philosophers. Did the Thals, then, spark the neutron war? Some dialogue could bolster that conclusion, especially Alydon’s asking Temmosus why the Daleks should trust them (the unspoken subtext is surely, “After all, we started it”). In this interpretation, the Dalek retreat into their fortified city becomes understandable, and their scheme to revenge themselves in the name of survival would likewise be comprehensible, though not morally defensible.

To some degree, the question of responsibility is moot. Neither these particular Thals nor these particular Daleks fought the war. (Presumably—there is some ambiguity on this point, as when Alydon tells Susan, “We are the last survivors of a great war.” Yet the Daleks speak of their “forefathers” retreating into the city, and both sides agree centuries have passed.) But viewing the Daleks, even if only briefly, as wounded victims unable to see their former enemies as having changed to peaceful people, let alone envisioning a mutually beneficial future with them, can prompt sobering reflection on war’s long-lasting consequences. Both Daleks and Thals are still seeking a sustainable existence, centuries after the bomb’s explosion. Had their ancestors the foresight to anticipate these consequences, might the war have been averted?

Fear Not to Live!

As in “An Unearthly Child,” in “The Daleks” we examine a tribe’s struggle to live and a leader’s struggle to earn, rather than simply claim, authority. We first see Alydon at the beginning of the third episode, cutting a visually impressive figure against a dark, lightning-punctuated sky. The scene in which a badly startled Susan sinks to her knees at her first sight of him evokes the appearance of angels in Scripture, especially Revelation 19.10: “I fell down at his feet to worship him, but he said to me, ‘You must not do that!’” (Given her second reaction of intense attraction to him—she’ll call him “magnificent”—the scene also carries a surprisingly erotic charge for 1960s family teatime television.) Alydon even greets Susan with that most angelic of salutations, “Don’t be afraid.” But he is no angel. I don’t mean he’s malicious; I simply mean he hasn’t yet matured into the trustworthy leader he must and does become by the story’s end.

As in “An Unearthly Child,” in “The Daleks” we examine a tribe’s struggle to live and a leader’s struggle to earn, rather than simply claim, authority. We first see Alydon at the beginning of the third episode, cutting a visually impressive figure against a dark, lightning-punctuated sky. The scene in which a badly startled Susan sinks to her knees at her first sight of him evokes the appearance of angels in Scripture, especially Revelation 19.10: “I fell down at his feet to worship him, but he said to me, ‘You must not do that!’” (Given her second reaction of intense attraction to him—she’ll call him “magnificent”—the scene also carries a surprisingly erotic charge for 1960s family teatime television.) Alydon even greets Susan with that most angelic of salutations, “Don’t be afraid.” But he is no angel. I don’t mean he’s malicious; I simply mean he hasn’t yet matured into the trustworthy leader he must and does become by the story’s end.

While the serial mostly frames Aldyon’s arc as an education in when fighting is necessary, I think we can also profit by considering his and his people’s journey as a course in learning how to live in the face of fear. “You can’t go on running away,” Ian tells Alydon at one point. Although Ian’s arguing partly (mostly?) from self-interest—they need the Thals’ help in recovering the TARDIS’ fluid link from the Daleks, after all—he also makes a valid point. Life cannot consist only of retreats.

The serial highlights this idea at several turns. At one level the Daleks themselves, of course, epitomize fearful withdrawal from the world. Rather than “using their brains for right” (in the Doctor’s words) and developing some way to adapt to post-bellum Skaro, as the Thals have through their drugs, the Daleks hide underground, intending to irradiate the planet further in order to force it to adapt to them, all other life be damned.

Susan makes her perilous, solitary journey through the petrified jungle in order to retrieve the anti-radiation drugs, despite being terrified by the task. In contrast, Antodus offers a negative example. Gripped with fear at having to jump the chasm outside the Dalek city and having already succumbed to despair— “Even if we do get through,” he frantically tells his brother Ganatus, “we’re all going to be killed… I’m not going on”—Antodus nearly costs Ian and Ganatus their lives, hanging from the rope over the abyss, screaming, “I can’t hold on!” His fear literally drags the two other men down, almost totally! His decision to cut the rope so Ian and Ganatus can live is a redemption of sorts, but such a tragic one, a crisis that could have been avoided had Antodus managed to find some more bravery.

Not that Antodus’ fears were completely unfounded. He had watched the mutated monsters in the swamp drag one of his fellows to his doom. He did appreciate the threat the Daleks posed. But he gave into his fear, rather than fighting through it. He did not appreciate Temmosus’ earlier words to Alydon: “I should always advise you to examine very closely what you think to be inevitable. It’s surprising how often apparent defeat can be turned to victory.” Alydon does ultimately take Temmosus’ words to heart, thus earning his role as head of the tribe. “My conclusion is this,” he says, summing up the case for helping the TARDIS travelers. “There is no indignity in being afraid to die. But there is a terrible shame in being afraid to live.”

Not that Antodus’ fears were completely unfounded. He had watched the mutated monsters in the swamp drag one of his fellows to his doom. He did appreciate the threat the Daleks posed. But he gave into his fear, rather than fighting through it. He did not appreciate Temmosus’ earlier words to Alydon: “I should always advise you to examine very closely what you think to be inevitable. It’s surprising how often apparent defeat can be turned to victory.” Alydon does ultimately take Temmosus’ words to heart, thus earning his role as head of the tribe. “My conclusion is this,” he says, summing up the case for helping the TARDIS travelers. “There is no indignity in being afraid to die. But there is a terrible shame in being afraid to live.”

As I listened to Alydon, I thought of words from one of my denomination’s confessions of faith: “Life is a gift to be received with gratitude and a task to be pursued with courage” (The Confession of 1967, 9.17). God freely and graciously grants us life, but not so we can be idle: instead, we exist to till and keep God’s good creation (Gen. 2.15); to love and serve our neighbors, our fellow recipients of life (Lev. 19.18); and above all and in all to glorify God (1 Cor. 10.31; Matt. 22.34-40).

Jesus Christ claims and saves us not only for eternal life in the next world, but also for abundant life in this one (John 10.10). What “terrible shame,” indeed, in doing anything less than fighting the good fight, finishing the race, and keeping the faith (2 Tim. 4.7)!

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version.

One comment on “Retro TARDIS Talk: “The Daleks” (Story 2: December 21, 1963-February 2, 1964)”