(You can read Part 1 of this TARDIS Talk here.)

The Beloved Doctor

When I first saw and immediately adored “The Eleventh Hour,” it didn’t take me long, being a sci-fi Christian, to start drawing parallels between the Doctor and Jesus. One long-time Who fan, also a Christian, cautioned me, “Don’t start seeing the Doctor as too much of a Christ figure.” She was right to warn me. The Doctor is too complicated and conflicted to be reduced to a stand-in for Jesus. Even so, he has his Christ-like moments, and one—or at least a quasi-Christ-like one—occurs at the climax of this story.

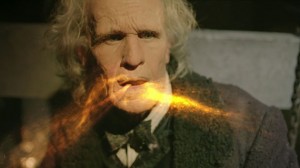

The Doctor sits on the roof of the clock tower as the Dalek fleet masses overhead. He’s been seen beneath foe-filled skies before (“The Eleventh Hour,” “The Pandorica Opens”), but now, unable to muster up a dazzling, defiant speech, he’s grimly resigned himself to death: “Knock yourselves out, boys. I’ve got nothing this time.” Just then, the crack that throughout series five represented danger and dread appears in the clouds, finally deserving to look like a smile. Through it, the Time Lords pour out upon the Doctor “a whole new regeneration cycle” in a golden swarm of light. Immediately energized, the old spring back in his step and the familiar twinkle back in his eyes, the Doctor leaps to his feet and unleashes the overflowing force of his regeneration against the Daleks (adopting, it must be said, a cruciform stance), becoming a glorious beacon signaling Trenzalore’s salvation.

The Doctor sits on the roof of the clock tower as the Dalek fleet masses overhead. He’s been seen beneath foe-filled skies before (“The Eleventh Hour,” “The Pandorica Opens”), but now, unable to muster up a dazzling, defiant speech, he’s grimly resigned himself to death: “Knock yourselves out, boys. I’ve got nothing this time.” Just then, the crack that throughout series five represented danger and dread appears in the clouds, finally deserving to look like a smile. Through it, the Time Lords pour out upon the Doctor “a whole new regeneration cycle” in a golden swarm of light. Immediately energized, the old spring back in his step and the familiar twinkle back in his eyes, the Doctor leaps to his feet and unleashes the overflowing force of his regeneration against the Daleks (adopting, it must be said, a cruciform stance), becoming a glorious beacon signaling Trenzalore’s salvation.

I was initially taken aback by the use of regeneration energy as a weapon. On reflection, however, the Doctor knows, from his spectacular regeneration in “The End of Time,” the process can be… messy. Why not channel some of that power in the Daleks’ direction, when it means successfully defending the town and its people?

Besides, the sight of a sudden blessing breaking forth from the heavens with power is one Christians may recognize. In fact, many Christian traditions will commemorate just such an event next Sunday (January 12, 2014). On the festival of the Baptism of the Lord, the church celebrates how Jesus, “coming up out of the water” of the River Jordan, “saw the heavens torn apart and the Spirit descending like a dove on him. And a voice came from heaven, ‘You are my Son, the Beloved; with you I am well pleased” (Mark 1.10-11). In the original Greek, the verb translated “torn apart” is schizo; the image is of a curtain ripped in two (and it’s an image Mark repeats at Jesus’ death, 15.38). God confirmed Jesus’ identity and empowered him to do his saving work.

Besides, the sight of a sudden blessing breaking forth from the heavens with power is one Christians may recognize. In fact, many Christian traditions will commemorate just such an event next Sunday (January 12, 2014). On the festival of the Baptism of the Lord, the church celebrates how Jesus, “coming up out of the water” of the River Jordan, “saw the heavens torn apart and the Spirit descending like a dove on him. And a voice came from heaven, ‘You are my Son, the Beloved; with you I am well pleased” (Mark 1.10-11). In the original Greek, the verb translated “torn apart” is schizo; the image is of a curtain ripped in two (and it’s an image Mark repeats at Jesus’ death, 15.38). God confirmed Jesus’ identity and empowered him to do his saving work.

Clara told the Time Lords they should love the Doctor. Their outpouring of regeneration energy through the crack shows they do. In empowering him with the energy he needs to do his work, the Time Lords confirm the Doctor’s identity. They say to him, in effect, “You are the Doctor, the beloved; with you we are well pleased.”

The Time Lords aren’t a consistent symbol for God in Doctor Who any more than the Doctor is one for Jesus. At this moment, however, their “baptism” of Gallifrey’s most famous son echoes a truth Christians know. As the late Donald Juel (a professor New Testament at Princeton Theological Seminary) explains, the torn-apart heavens at Jesus’ baptism point to “the intrusion of God into a world that has become alien territory—an intrusion that means both death and life” (Juel, A Master of Surprise, Fortress: 1994, p. 36). Through the Doctor’s unprecedented thirteenth regeneration, a tremendous power intrudes into the universe. For those, like the Daleks, who oppose this power’s chosen agent, that intrusion means death. But for those, like the people of Christmas and like Clara, who accept and embrace and love him, that intrusion means life.

“When the Doctor Was Me”

I can’t praise Smith’s second, more reflective regeneration scene highly enough, in its scripting or its execution. I think it, too, has biblical, Christ-like overtones—for example, Clara’s initial relief at seeing the Doctor just as he was, only to be told she’s seeing “just the reset,” made me think of the risen Jesus telling Mary Magdalene, “Do not hold on to me” (John 20.17)—but its attention to detail (the bowl of fish custard, the shedding of the bow tie, the cameos from little Amelia and grown Amy—all wonderful) and its deep, honest emotion are what make it stand out. Against Clara’s understandable grief at losing “her Doctor”—“Please don’t change,” she pleads—stand the Doctor’s own fascination with his new regeneration cycle’s mechanics (“Taking a bit longer”) and his contemplative acceptance of what (of who) is to come.

I can’t praise Smith’s second, more reflective regeneration scene highly enough, in its scripting or its execution. I think it, too, has biblical, Christ-like overtones—for example, Clara’s initial relief at seeing the Doctor just as he was, only to be told she’s seeing “just the reset,” made me think of the risen Jesus telling Mary Magdalene, “Do not hold on to me” (John 20.17)—but its attention to detail (the bowl of fish custard, the shedding of the bow tie, the cameos from little Amelia and grown Amy—all wonderful) and its deep, honest emotion are what make it stand out. Against Clara’s understandable grief at losing “her Doctor”—“Please don’t change,” she pleads—stand the Doctor’s own fascination with his new regeneration cycle’s mechanics (“Taking a bit longer”) and his contemplative acceptance of what (of who) is to come.

Smith plays his last scene as one who has finally, only in this moment, grasped a key secret of life; he articulates it, haltingly but urgently, to Clara as though the thoughts are occurring to him in just this way for the very first time, just in time:

We all change, when you think about it. We’re all different people all through our lives. And that’s okay, that’s good, you’ve got to keep moving, so long as you remember all the people that you used to be. I will not forget one line of this. Not one day. I swear. I will always remember when the Doctor was me.

The Eleventh Doctor’s epiphany is a nice answer to The Moment’s characterization of him, in “The Day of the Doctor,” as “the man who forgets.” No more (to coin a phrase)! As he showed in his interaction with the War Doctor in that episode, he has learned to look back on his life, on himself, with honesty but also with compassion; not judging, but remembering and learning for the future. In other words, the Doctor has become a fully integrated individual. He is whole. He is at peace. This being Doctor Who, I don’t expect he’ll permanently stay that way after his regeneration; healthy, fully integrated individuals at peace with themselves don’t usually make very interesting protagonists. But if this year’s fiftieth anniversary festivities have demonstrated anything, they’ve shown there is a fundamental core to the character, spanning five decades and twelve different actors in the role. The Doctor is always both “a-coming” and already here.

The Eleventh Doctor’s epiphany is a nice answer to The Moment’s characterization of him, in “The Day of the Doctor,” as “the man who forgets.” No more (to coin a phrase)! As he showed in his interaction with the War Doctor in that episode, he has learned to look back on his life, on himself, with honesty but also with compassion; not judging, but remembering and learning for the future. In other words, the Doctor has become a fully integrated individual. He is whole. He is at peace. This being Doctor Who, I don’t expect he’ll permanently stay that way after his regeneration; healthy, fully integrated individuals at peace with themselves don’t usually make very interesting protagonists. But if this year’s fiftieth anniversary festivities have demonstrated anything, they’ve shown there is a fundamental core to the character, spanning five decades and twelve different actors in the role. The Doctor is always both “a-coming” and already here.

Would that we could all look on our lives, on ourselves, in this way! When I review the different people I’ve been through my life, I find moments in which I still feel regret or embarrassment or guilt as keenly as I did the first time around. It’s not that I have nothing to be regretful or embarrassed or guilty about, of course, but those emotions can block me from learning those moments’ lessons and fully living in the present while looking forward to the future, as the Doctor does. I tend to be so judgmental of myself—and I suspect, to some degree or other, you’re the same way. It seems part of the fallen human condition.

“For our sense of security,” writes Trappist monk John Jacob Raub, “we have to see ourselves as continually judging, continually dividing into good and bad and we naturally project our mental workings onto God. It is difficult for us to realize that the divine mind is not like our human mind. The human mind (the result of eating of the tree of good and evil) is split. The divine mind (symbolized by the tree of life) has no such split. God’s mind is whole” (Who Told You That You Were Naked?; 1992: Crossroad, p. 108).

The apostle Paul urges us to be “transformed by the renewing of our minds”—a regeneration (so to speak) of mindset, of attitude and outlook, of will, that we might “discern the will of God—what is good and acceptable and perfect” (Rom. 12.2). Surely it is God’s will that we share the whole, integrated, peaceful divine mind, “the same mind… that was in Christ Jesus” (Phil. 2.5). (In that last verse’s immediate context, Paul’s talking about humbly serving others, but we can’t do so if we are continually judging others and ourselves as good or evil.)

Jesus came “that [we] may have life, and have it abundantly” (John 10.10), and I think he means more than the kind of wholeness the Doctor demonstrates, he doesn’t mean less. His miracles of healing signify the unity, the holistic well-being, the shalom he makes possible. “Peace I leave with you,” he tells his friends, “my peace I give to you… Do not let your hearts be troubled, and do not let them be afraid” (John 14.27).

As the Doctor faces his new iteration with a peace-filled and unafraid heart (even if he doesn’t like the color of his new kidneys), may we, too, in this New Year, look back on the people we have been with peace, and look forward to the people we will be without fear, knowing that our times are in the nail-scarred, loving hands, not of a Time Lord, but of the Lord of Time, who is “the same yesterday and today and forever” (Hebrews 13.8).

As the Doctor faces his new iteration with a peace-filled and unafraid heart (even if he doesn’t like the color of his new kidneys), may we, too, in this New Year, look back on the people we have been with peace, and look forward to the people we will be without fear, knowing that our times are in the nail-scarred, loving hands, not of a Time Lord, but of the Lord of Time, who is “the same yesterday and today and forever” (Hebrews 13.8).

All Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version.

I thought Trappist monks just made beer. 😉

Jellies, too, I think. (But perhaps not jelly babies!)