“Last Christmas” is the most ambitious Christmas special Doctor Who has given us. What other adjective adequately describes a holiday entertainment that asks viewers to both disavow belief in Santa Claus and confront their own mortality?

It’s certainly the creepiest Yuletide adventure of Doctor Who. I wondered how Peter Capaldi’s darker, dour Doctor could fit into a Christmas story. Steven Moffat proved the character could fit quite nicely by crafting a shadow-filled, suspenseful tale of a base under seasonally flavored siege from some truly disgusting critters. Reminiscent of Alien’s face-huggers though they are (a criticism Moffat wisely takes a preemptive swipe at in the script itself), the Dream Crabs are still nothing I’d want to see dropping down my chimney, and not simply because they’re physically repulsive. Their ability to cause unending, existential angst about one’s grip on reality is equally terrifying. All in all, they’re another worthy addition to Moffat’s menagerie of monsters.

The episode’s strong horror quotient isn’t quite offset by its humor, but some genuinely good laughs do come. The two “comedy elves” (one of whom is Dan Starkey relieved of his Strax make-up for a change), provide some welcome comic relief, especially when mocking the idea that all those gifts Santa brings are really given by children’s parents—“a lovely story!”—or instructing Shona (Faye Marsay in a winsome performance) in the “basic physics” of a “stripy” North Pole (“Otherwise, you couldn’t see it moving ’round”).

“A Dream Trying to Save Us”

Nick Frost makes the Santa Claus of everyone’s dreams—which, given the episode’s plot, is as it should be. When he showed up in the mid-credit “stinger” of “Death in Heaven,” some fans worried the character’s presence would only weigh the episode down with silliness and sentimentality (because, goodness knows, Doctor Who is never, ever afflicted with either of those problems on its own). Here, too, however, Moffat inventively disarms naysayers, pointing out and playing with multiple parallels between Santa and the Doctor. Both characters are “impossible,” equipped with their own brands of magic (whether police boxes or sleighs that are “bigger on the inside”) and a desire to do good.

Nick Frost makes the Santa Claus of everyone’s dreams—which, given the episode’s plot, is as it should be. When he showed up in the mid-credit “stinger” of “Death in Heaven,” some fans worried the character’s presence would only weigh the episode down with silliness and sentimentality (because, goodness knows, Doctor Who is never, ever afflicted with either of those problems on its own). Here, too, however, Moffat inventively disarms naysayers, pointing out and playing with multiple parallels between Santa and the Doctor. Both characters are “impossible,” equipped with their own brands of magic (whether police boxes or sleighs that are “bigger on the inside”) and a desire to do good.

When Shona asks if Santa is “a dream trying to save us,” Santa replies, “I think you just defined me!” While I don’t think I can fully embrace that formulation of Santa’s significance, I do appreciate the intent. As many of us at The Sci-Fi Christian have said many times, stories—the dreams and daydreams that occupy our imagination—really do matter. I don’t think the story of Santa Claus is the best story we can tell ourselves or our children at Christmas (it’s not Santa’s birthday, after all, nor even Saint Nicholas of Myra’s—though his is another story worth knowing and sharing); however, if told to emphasize the importance of giving rather than receiving, and if told in ways that open us to mystery and wonder, it’s not a bad story, either. And, as G.K. Chesterton found, belief in Santa may even sometimes help prepare the heart for belief in God’s grace: “What we believed [as children] was that a certain benevolent agency did give us those toys for nothing. And, as I say, I believe it still. I have merely extended the idea.”

Santa tells our protagonists, “I have watched over you all your lives. I’ve taken care of you from Christmas to Christmas… And [not being real] never stopped me.” There can be value, this episode argues, in believing the impossible, in surrendering ourselves to the imaginary. Embracing the dreams of childhood can help us face the realities of adulthood. For some people, God and Jesus are no more real than Santa Claus (or, for that matter, “a time-travelling scientist dressed as a magician”—“Classic!”). But Christians can affirm, as did J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis, that the story we celebrate at Christmas is a dream come true, the only story worthy of our full surrender.

“Every Christmas is Last Christmas”

I found Clara’s dream holiday with Danny the hour’s most moving sequence. The matryoshka-like “dreams within dreams” structure of the script owes an obvious debt to Inception, but Clara’s Christmas dream reminded me more (incorrigible Trekkie that I am) of Star Trek: Generations. As it did for Captain Picard in that film, an illusory, light- and love-filled Christmas becomes, for Clara here, a dangerous snare to escape.

I found Clara’s dream holiday with Danny the hour’s most moving sequence. The matryoshka-like “dreams within dreams” structure of the script owes an obvious debt to Inception, but Clara’s Christmas dream reminded me more (incorrigible Trekkie that I am) of Star Trek: Generations. As it did for Captain Picard in that film, an illusory, light- and love-filled Christmas becomes, for Clara here, a dangerous snare to escape.

Instead of becoming, as it easily might have, a “downer,” Danny’s statement that “every Christmas is last Christmas” emerges as a stirring summons to appreciate the gift of the present moment and the people around us. We “have no idea what tomorrow will bring,” the apostle James cautions us; we “are no more than a mist, seen for a little while and then disappearing” (James 4.14, Revised English Bible). Granted, James’ stern word of warning addresses a different concern than Danny’s admonition that Clara “get the hell on with” her life “every single second,” but I think it can complement Dream Danny’s insight (which, I guess, is actually Clara’s?). We cannot presume we know the future, or that our future—at least on this earth, a future marked by the changing of the seasons and the coming and going of holidays—is guaranteed.

How might we celebrate Christmas differently, all of us—both those who celebrate for religious reasons and those who celebrate culturally (with professed Christians frequently falling into both of those categories)—if we really believed each Christmas could be our last? Maybe we’d slow down in December, rather than attempting to cram more activity into our already over-scheduled lives. Perhaps the purchase of gifts would become less urgent—or maybe we’d be more motivated to give material goods to those who truly need them. I don’t think Danny’s words (or James’) will guide American Christmases any time soon, but they might change our celebrations, and us, for the better.

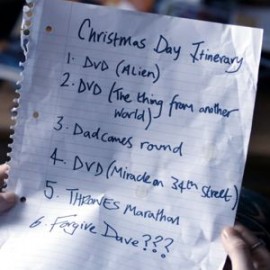

At least Shona, it seems, comes to this realization when she finally awakens from her dream. We don’t know who Dave is or why she feels she must forgive him, but knowing she has resolved to means she is making a positive change. May this Christmastide and New Year find us all, by the grace of God, making such positive changes–no longer believing in Santa (perhaps), but certainly believing, as the Doctor now does, in the possibility of joyful second chances.

At least Shona, it seems, comes to this realization when she finally awakens from her dream. We don’t know who Dave is or why she feels she must forgive him, but knowing she has resolved to means she is making a positive change. May this Christmastide and New Year find us all, by the grace of God, making such positive changes–no longer believing in Santa (perhaps), but certainly believing, as the Doctor now does, in the possibility of joyful second chances.

Leave a Reply