Ultimate Spider-Man #1-#3 (Nov.-Dec. 2011). Brian Michael Bendis, writer. Sara Pichelli, artist.

In Part 1, I argued that we need to get to know Miles Morales as we would get to know anyone in real life: as the person he really is, in all of his particularities. When we get to know Miles Morales in particular, then, who do we meet? We meet a young teen (the recap page in issue #3 calls him a “grade-schooler,” but he looks like he’s at least in sixth grade) growing up in a tough Brooklyn neighborhood, trying to come to terms with a problem that perplexed no less a thinker than Qohelet, “the Teacher” in Ecclesiastes: “Again I saw that under the sun the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, nor bread to the wise, nor riches to the intelligent, nor favor to the skillful; but time and chance happen to them all” (Eccl. 9.11).

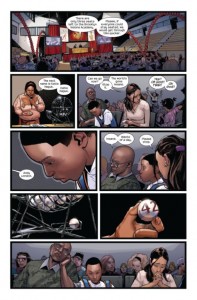

Miles doesn’t quote Scripture, but his kinship with Qohelet is clear from the moment we meet him in issue #1. Miles is reluctantly on his way to a lottery for a place in a prestigious new charter school. His nervous mother is preparing him for what she thinks is inevitable disappointment: “This is not a reflection on you… This has nothing to do with you as a person.” Miles says he already knows this fact, and he does. That’s what’s bothering him. When his number is drawn (the number 42, an apparent tip of the hat to Douglas Adams’ take on the random ways of life, the universe, and everything), Miles, caught up in an embrace by his now ecstatic mother, looks over her shoulder at a lonely, less lucky girl who is sobbing. “It shouldn’t—all these other kids,” Miles haltingly says. “Should it be like this?” Should advantage and opportunity be such a scattershot affair? Shouldn’t the world be more just than that?

That’s the question haunting Qohelet, too–the question that, in the end, drives him to consider life so much as “chasing after wind” (2.26). Whether he considers the fleeting value of earthly pleasures or the hard facts that vice often prospers more than virtue and that death awaits the wise and foolish alike, Qohelet can only conclude that, while God has a plan for all that happens under the sun, we mere mortals can’t begin to figure it out (3.11; 8.16-17). The best we can do is enjoy the life and labor God has given us while we can, because the only certainty the future offers is the grave (3.22; 9.7-10).

To a certain extent, Miles’ family offers similar advice: spend less time worrying about what should be and focus on what is. “Just focus on you,” his mother tells him. “You got in. Focus on that.” I don’t think she’s telling him to be selfish or egotistical. She’s urging him, not unlike Qohelet urged his hearers, to make the best of an unfair world.

“It’s the Hardest Thing”

Miles’ uncle Aaron, however, holds out a possibility Qohelet never did. He tells Miles, “You got your ticket out of this cesspool. You make your own way. Your dad and me didn’t have a chance in that school we went to… You learn. You study. And you make the world the way you want it to be, not the way it is. You make it. Don’t let people make it for you.”

Qohelet declared all human striving to be “vanity of vanities” (1.2; 12.8; or, “Everything is meaningless!,” NIV; or Eugene Peterson’s paraphrase in The Message, “It’s all smoke, nothing but smoke”). He doesn’t easily allow for the possibility of making the world better, for oneself or for others. And that’s the danger inherent in Qohelet’s philosophy. Taken to its extreme, it reifies all those evils under the sun that trouble him. It tacitly accepts wickedness in the place of justice (3.16) and oppression of the powerless (4.1) as the only way things can be—possibly even, Qohelet disturbingly suggests, the way God wants them to be: “I said in my heart with regard to human beings that God is testing them to show that they are but animals” (3.18). It’s an attitude that informs the stanza modern hymnals routinely excise from “All Things Bright and Beautiful”:

The rich man in his castle,

The poor man at his gate,

He [i.e., God] made them, high or lowly,

And ordered their estate.

Uncle Aaron could never sing those words. Neither could Miles’ father. He also urges Miles to make a better life for himself. The father’s perspective, however, differs from the uncle’s. Aaron and his brother (unless I’ve missed them, neither of Miles’ parents have been given names, so let’s call Dad “Mr. Morales” for now) used to be partners in crime. Aaron is still a thief: his high-tech break-in at Osborn Industries is the first issue’s first action sequence. But Mr. Morales has long been a law-abiding citizen. In issue #2, he explains why he doesn’t want Miles spending time with Uncle Aaron. He confesses the brothers’ past in a few pages of morally earnest but utterly convincing script. Mr. Morales says, “When we were kids we didn’t have—we didn’t see any other opportunity coming our way. Not saying that we didn’t have other opportunities… I’m just saying we couldn’t see them.”

We see both Aaron and Mr. Morales’ positive and negative traits in these first few issues. Bendis presents engaging, fully realized characters; not cardboard cutouts for a melodrama. And, yes, Mr. Morales does want to look better in his son’s eyes than Aaron. Having said all that, I think Mr. Morales correctly identifies his brother’s mistake. Although he loves his brother, Mr. Morales goes so far as to use the word “temptation” when talking about the danger he believes Aaron is to Miles. He’s afraid Aaron will, either directly or indirectly, persuade Miles to seek a quick and easy way out of tough circumstances. Where Aaron implicitly abdicates any responsibility for his life of crime by saying he “didn’t have a chance,” Mr. Morales calls on Miles to be a more active moral agent: “Anyone can be bad, anyone. It’s easy… But to stay focused. To live a good life… it’s the hardest damn thing.”

We see both Aaron and Mr. Morales’ positive and negative traits in these first few issues. Bendis presents engaging, fully realized characters; not cardboard cutouts for a melodrama. And, yes, Mr. Morales does want to look better in his son’s eyes than Aaron. Having said all that, I think Mr. Morales correctly identifies his brother’s mistake. Although he loves his brother, Mr. Morales goes so far as to use the word “temptation” when talking about the danger he believes Aaron is to Miles. He’s afraid Aaron will, either directly or indirectly, persuade Miles to seek a quick and easy way out of tough circumstances. Where Aaron implicitly abdicates any responsibility for his life of crime by saying he “didn’t have a chance,” Mr. Morales calls on Miles to be a more active moral agent: “Anyone can be bad, anyone. It’s easy… But to stay focused. To live a good life… it’s the hardest damn thing.”

Mr. Morales sounds a bit like Jesus (well, except for the swearing). Jesus tells his followers, “Enter through the narrow gate; for the gate is wide and the road is easy that leads to destruction, and there are many who take it. For the gate is narrow and the road is hard that leads to life, and there are few who find it” (Matt. 7.13-14). Now, my Protestant hackles go up when I read words like those. Come on, Jesus, haven’t you heard about “grace alone?” But even the apostle Paul, the great herald of grace, taught that grace is no excuse to keep on sinning (Rom. 6.1-2). The road that leads to the next life runs through this one; and while God’s grace alone sets us on that road, Jesus still calls us to follow it—to follow Him—faithfully. At times, we’ll stumble. At other times, as Mr. Morales’ words to Miles suggest, we’ll be tempted to stray from the course, simply because the course is hard. Of course, Jesus warned us it would be (see also Luke 9.57-62; John 15.20). But since it is the road that leads to life, why would we want to travel any other?

“Not That Guy” (Or Are You?)

As was the “Ultimate” retelling of Peter Parker’s origin story a decade ago, the new Ultimate Spider-Man is an exercise in decompressed storytelling. Three issues into the run, Miles has yet to don the (way cool) black-and-red costume he sports on the covers. But Bendis’ leisurely pace allows readers to appreciate fully the massive changes Miles is confronting. Miles’ friend Ganke tells him in issue #3, “You won a lottery!”

As was the “Ultimate” retelling of Peter Parker’s origin story a decade ago, the new Ultimate Spider-Man is an exercise in decompressed storytelling. Three issues into the run, Miles has yet to don the (way cool) black-and-red costume he sports on the covers. But Bendis’ leisurely pace allows readers to appreciate fully the massive changes Miles is confronting. Miles’ friend Ganke tells him in issue #3, “You won a lottery!”

He’s referring to Miles’ place at Brooklyn Visions Academy, but he might as well be referring also to the spider bite Miles received at Uncle Aaron’s apartment (Aaron unknowingly gave the mutated arachnid a lift home from the Osborn lab). Like the ball drawn in the literal lottery, the spider bears the number 42, alerting readers that Miles has also won a metaphorical lottery, as Ganke immediately realizes: “You’re Spider-Man! YOU ARE!! You got bit by a spider. He got bit by a spider. You can walk on walls, he can… This is the best news ever…” (I would have liked Ganke to tell Miles, “Face it, tiger: you hit the jackpot”—but I guess that might’ve been just a little too precious and predictable, huh?)

Miles, however, doesn’t see his new spider powers as good news at all. (And, incidentally, he does have some truly new spider powers, including invisibility and a “stinger,” which will further differentiate him from Peter Parker). Miles just wants to be normal. He laments, “Why are there spiders running around the city biting people and giving them spider powers?” (that’s the kind of dialogue you only get from superhero stories, and I love it!). But when he sees the proverbial people trapped in a burning building, he knows he has to try and save them. He does—and immediately vows, “Never again… There’s already a Spider-Man and he seems to love… jumping around and being lit on fire. I’m not that guy. Let him do that. I’m not that guy.” It’s a sobering conclusion to several exciting pages of action that, in a sloppier storyteller’s hands, could have ended with Miles embracing his heroic destiny to the accompaniment of an epic John Williams score. But Bendis knows Miles has a long way to go before we see him in his suit (the events take place prior to Miles’ first published appearance in Ultimate Fallout #4), and he’s going to tell the tale taking as many emotional, character-driven beats as it needs.

Miles’ initial resistance to the call to adventure (I assume it’s only initial; otherwise, the book will have a really short run) does more than satisfy the structural requirements of Joseph Campbell’s monomyth. It echoes any number of heroes from the Bible’s pages who, when confronted with God’s call and claim on their lives, protested, “Let others do that. I’m not that guy.”

- Moses told God, “Let Aaron go down and tell old Pharoah, ‘Let my people go.’ I’m just not that guy” (and that was just one of Moses’ objections; see Ex. 3.13-4.17).

- Gideon told God, “Let someone else take on our Midianite oppressors. I’m just not that guy.” Then he asked for not one, not two, but three signs as proof, to boot! (see Judges 6.11-24, 36-40).

- Jeremiah told God, “Let someone else be your prophet to the nations. I’m just a kid. I’m just not that guy” (see Jer. 1.4-9).

But the biblical hero of whom Miles, at this point, reminds me the most is a heroine. The book of Esther is one of only two books in the Hebrew Bible lacking any explicit mention of God (the other is the Song of Solomon). When Mordecai approaches the new queen, however, urging his niece to use her influence with the king to save their people from Haman’s genocidal designs, readers can have little doubt that this particular “call to adventure” really comes from God. Esther initially insists that she is “just not that gal,” but her uncle presses her: “Do not think that in the king’s palace you will escape any more than all the other Jews… Who knows? Perhaps you have come to royal dignity for just such a time as this” (Esther 4.13-14).

Ganke is the Mordecai to Miles Morales’ Esther. Granted, Ganke’s not quoting Scripture any more than Miles is; Ganke’s best argument in favor of “figuring out” and putting to use Miles’ powers is, simply, “I mean we have to.” (That, and his very funny, exasperated “threat” to the moping Miles, “Well, fine… I’ll get the spider to bite me. At least one of us can fight crime and get girls and enjoy it.”) When the news reaches the Visions Academy at the end of issue #3 that Spider-Man has been shot (in Ultimate Comics Spider-Man #160), it seems extremely likely that Miles’ spider-bite was more than an accident, but happened “for just such a time as this.” Miles, whom we have seen worrying about the unequal distribution of opportunity, has now been handed two incredible opportunities. I expect subsequent issues will show him, eventually, making the most of those opportunities—and even using them to create new opportunities, new beginnings, for others, even as he did for the people in that burning building.

Ganke is the Mordecai to Miles Morales’ Esther. Granted, Ganke’s not quoting Scripture any more than Miles is; Ganke’s best argument in favor of “figuring out” and putting to use Miles’ powers is, simply, “I mean we have to.” (That, and his very funny, exasperated “threat” to the moping Miles, “Well, fine… I’ll get the spider to bite me. At least one of us can fight crime and get girls and enjoy it.”) When the news reaches the Visions Academy at the end of issue #3 that Spider-Man has been shot (in Ultimate Comics Spider-Man #160), it seems extremely likely that Miles’ spider-bite was more than an accident, but happened “for just such a time as this.” Miles, whom we have seen worrying about the unequal distribution of opportunity, has now been handed two incredible opportunities. I expect subsequent issues will show him, eventually, making the most of those opportunities—and even using them to create new opportunities, new beginnings, for others, even as he did for the people in that burning building.

May God grant us, in whatever circumstances we find ourselves, the wisdom and insight and grace to see and seize whatever opportunities we can to do good for others; walking the narrow way that leads to life, and showing others, through our words and our deeds, the One who is himself the Way, the Truth, and the Life.

Except as noted, Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version.

Leave a Reply