If you really enjoy reading, every day is Book Lovers’ Day; but tomorrow, the first Saturday in November, is, at least by someone’s reckoning, a day set aside to celebrate the joys of reading for pleasure.

To mark the occasion, here are my top five, best-loved fictional books: books that don’t exist except as key elements of the science fiction and fantasy stories in which they appear. The Bible tells us, “Of making many books there is no end” (Eccles. 12.12)–but of the making of these books, there hasn’t even been a beginning!

5. To Serve Man (from The Twilight Zone, “To Serve Man,” written by Rod Serling from a story by Damon Knight, directed by Richard L. Bare, first aired March 2, 1962)

Actually, I suppose To Serve Man would only rank high on a “best-loved book” list prepared by a Kanamit… If by some twist of fate as bizarre as those portrayed on the series, you’ve never seen or heard about this particularly delicious morsel from The Twilight Zone, here’s a fast-food version found on YouTube:

Even after fifty years, the moral of the story satisfies: Beware aliens bearing books!

Speaking of which…

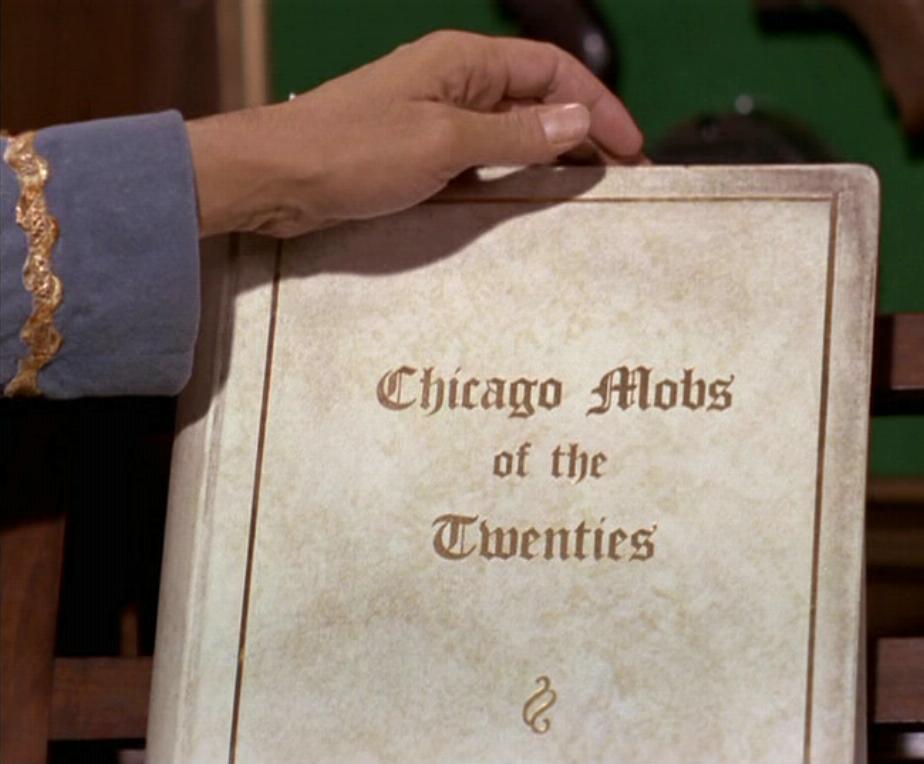

4. Chicago Mobs of the Twenties (from Star Trek, “A Piece of the Action,” written by David P. Harmon and Gene L. Coon, directed by James Komack, first aired January 12, 1968)

“Hey, don’t go knockin’ The Book!” Published on Earth in 1992 and, nearly two centuries later, left behind on the planet Sigma Iotia II by a careless Starfleet landing party, this history of organized crime in the Windy City, from the big bosses to the small-fry, inspired the “highly imitative” Iotians to create a civilization where Al Capone would feel right at home.

Everyone else loves the tribbles, but I say “A Piece of the Action” is comedic Star Trek at its best. Spock giving Kirk a driving lesson… Scotty threatening guest star Vic Tayback (the Mel whom Flo was always telling to “kiss her grits” on Alice) with “concrete galoshes”… Kirk explaining the nonsensical rules of fizzbin… and, of course, The Book: the funniest example of cultural contamination in the Star Trek canon. I’ve also sometimes wondered if The Book may be more than a mere plot point. The slavish and unthinking devotion of the Iotians to their “sacred text,” bound in gilded white leather and enthroned on a lectern, may offer us Christians a chance to learn how not to read our “Book,” the Bible. As one preacher I knew was fond of saying, “Any text without a context is a pretext!”

Everyone else loves the tribbles, but I say “A Piece of the Action” is comedic Star Trek at its best. Spock giving Kirk a driving lesson… Scotty threatening guest star Vic Tayback (the Mel whom Flo was always telling to “kiss her grits” on Alice) with “concrete galoshes”… Kirk explaining the nonsensical rules of fizzbin… and, of course, The Book: the funniest example of cultural contamination in the Star Trek canon. I’ve also sometimes wondered if The Book may be more than a mere plot point. The slavish and unthinking devotion of the Iotians to their “sacred text,” bound in gilded white leather and enthroned on a lectern, may offer us Christians a chance to learn how not to read our “Book,” the Bible. As one preacher I knew was fond of saying, “Any text without a context is a pretext!”

3. The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (from… well, it’s obvious, isn’t it?)

Douglas Adams’ extended, uproarious riff on the Encyclopedia Galactica from Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series, “H2G2” is (as it itself will tell you) is “a wholly remarkable book”:

Don’t have your own copy of the Guide yet? Don’t panic—there’ll be an app for that. (Towel not included.)

2. The Red Book of Westmarch (from J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings, 1954-55)

Tolkien always contended he didn’t so much “create” Middle-earth as “discover” it. The Lord of the Rings’ prefatory matter and appendices indicate the narrative was drawn from a primary source, the Red Book of Westmarch, in much the same way that, for example, Sir Thomas Malory crafted Le Morte d’Arthur from older, French sources. Ever the scholar, Tolkien’s references to and citations of the Red Book occasionally convince fans that it really exists.

Tolkien always contended he didn’t so much “create” Middle-earth as “discover” it. The Lord of the Rings’ prefatory matter and appendices indicate the narrative was drawn from a primary source, the Red Book of Westmarch, in much the same way that, for example, Sir Thomas Malory crafted Le Morte d’Arthur from older, French sources. Ever the scholar, Tolkien’s references to and citations of the Red Book occasionally convince fans that it really exists.

The Red Book began life as Bilbo’s diary of his adventures in The Hobbit (1937); that novel takes its subtitle, “There and Back Again,” from the title Bilbo gave his own story. During his years in Rivendell, Bilbo expanded the manuscript, adding much history and lore from Middle-earth’s past. He bequeathed the volume to Frodo, who wrote in it an account of the Fellowship’s exploits at the close of the Third Age titled (in part), The Downfall of the Lord of the Rings and the Return of the King. Finally, Frodo left the book to faithful Sam Gamgee:

“Why, you have nearly finished it, Mr. Frodo!” Sam exclaimed. “Well, you have kept at it, I must say.”

“I have quite finished, Sam,” said Frodo. “The last pages are for you.”

Not unlike the Bible, the Red Book is a collection of books that, when read together, form a continuous narrative of salvation: a single, generations-spanning storyline of the world’s creation, fall, and redemption, accomplished through some of the unlikeliest means of all. It’s no accident that Tolkien, a devout Roman Catholic, would have as one of his epic fantasy’s major themes the truth taught by the apostle Paul: “God chose what is foolish in the world to shame the wise; God chose what is weak in the world to shame the strong; God chose what is low and despised in the world, things that are not, to reduce to nothing things that are, so that no one might boast in the presence of God” (1 Cor. 1.27-29, NRSV).

And finally, since one good Inkling deserves another…

1. The Magician’s Book (from C.S. Lewis, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, 1952)

In chapter 10 of the third book (as published) in Lewis’ “Chronicles of Narnia,” Lucy begins reading an illustrated book of spells that soon casts a “spell” over her (our modern word “spell” comes, in fact, from an Old English word meaning “speech” or “story;” the Gospel is God’s story, or “God’s spell”).

Ultimately, Lucy stops reading spells and starts reading a story like no other. “When she had got to the third page and come to the end, she said, ‘That is the loveliest story I’ve ever read or ever shall read in my whole life. Oh, I wish I could have gone on reading it for ten years. At least I’ll read it over again.’ But here part of the magic of the Book came into play. You couldn’t turn back… ‘It was about a cup and a sword and a tree and a green hill, I know that much. But I can’t remember, and what shall I do?’… And she never could remember; and ever since that day what Lucy means by a good story is a story which reminds her of the forgotten story in the Magician’s Book.”

Christians, too, know a story involving a cup and a sword, a tree and a green hill. It is The Story standing behind all “good stories.” And in our world—the world where we must all, like Lucy and Edmund, learn to know Aslan by another name—we are fortunate that we can not only read that story again and again but also share it with others so that they, too, may discover their place in it.

Do you even need to ask? The Necronomicon, of course. Loosely translated to “The Book about he Dead,” it was invented by H. P. Lovecraft as his ancient tome that, simply by reading its pages, could drive men insane. Written by the Mad Arab, Abdul Alhazared, who was killed by unseen forces in the middle of a street in broad daylight, Lovecraft used it as a book to add credence to his occult reference and mythos. Contrary to popular belief, it definitely does not exist, though many works have used its name.

Excellent addititon to the list, Joshua — thanks!