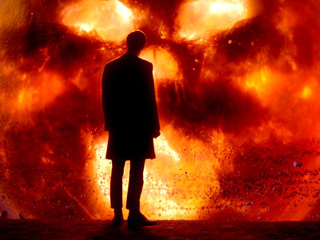

The Doctor takes on an “old god” by telling a new story—one that may not be as opposed to “the old, old story” as many people think!

(As ever, “TARDIS Talk” treats everything officially aired through the most recent episode as fair game, so here there be spoilers!)

I apologize for this tardy “TARDIS Talk.” I try to watch an episode at least twice before committing comments to paper, but real life prevented me from revisiting “Real Clara”’s second episode as quickly as I would have liked.

Had I written about the show after a single viewing, I likely would have focused on the fact that it felt like a retread of “The Beast Below” (5.2), at times beat for beat. I know “Beast” divides fans, but I immensely enjoy it, more with every viewing (probably a half-dozen to date). So when “Rings” seemed to be ripping it off, I wasn’t pleased.

Had I written about the show after a single viewing, I likely would have focused on the fact that it felt like a retread of “The Beast Below” (5.2), at times beat for beat. I know “Beast” divides fans, but I immensely enjoy it, more with every viewing (probably a half-dozen to date). So when “Rings” seemed to be ripping it off, I wasn’t pleased.

Consider: the Doctor, eager to show his new young, female companion some astonishing venue, lands the TARDIS (following a brief appreciation of the destination from afar) to a busy, alien society’s marketplace. He and the companion are quickly separated. The companion soon befriends a much younger girl who offers tantalizing clues about a great, hidden mystery. The young girl is in some kind of peril and cries, her tears acting as a catalyst for the Doctor and the companion’s involvement. The mystery they must solve centers on a large creature around which the society is (knowingly or not) organized. Resolution occurs only after the Doctor uncovers the truth about that society’s connection to the creature, which leads to a dramatic emotional outburst (complete with mention of the Time War). When the Doctor’s intervention proves insufficient, the new companion proves her worth by making up for what is lacking in the Doctor’s sufferings. Order is restored, and the bond between the Doctor and the companion is cemented. (“Rings” even commits the same kind of scientific groaners as does “Beast”: for example, how do the Long Song’s sound waves—let alone the Doctor and Clara on their space moped—travel through the vacuum of space? Not even a throwaway line about an atmospheric bubble thrown to us this time!)

Having seen “Rings” again, I’d argue these parallels still hold, but I find myself thinking that “Rings” feels more coherent than “Beast,” and also that it offers some different food for thought.

A Person, not a Puzzle

Last week I wrote that “people are more interesting as individuals than as puzzles to be solved.” Clara feels the same way! Her insistence that the Doctor treat her as herself and no one else was a welcome moment. “Rings,” unlike “The Bells of Saint John,” presents a Clara who really is her own person. Her backstory is established deftly; the script spends just enough time on her past so we can empathize with her loss of her mother, but not so much that we become maudlin about it. And “Rings” reinforces Clara as a truly kind and caring individual, someone we believe would follow Merry Galel (love that kid’s name) simply because Merry looked lost and in need of help.

The scene in which Clara gives the young “Queen of Years” courage by recounting her own childhood experience of being lost and found made me think of the apostle Paul’s discussion of consolation in 2 Corinthians: God “comforts us in all our trouble so that we can comfort other people who are in every kind of trouble. We offer the same comfort that we ourselves received from God” (1.4, CEB). In his original Greek, Paul uses forms of the verb parakaleo and noun paraklesis, both of which have a root meaning of, “to call alongside of.” Think about Jesus’ identification of the Holy Spirit as the Paraclete in John 14.16 et al.—the Spirit is our “helper,” our “comforter,” our “advocate,” because the Spirit comes alongside to encourage and strengthen us. Clara demonstrates that encouraging compassion and advocacy as she comes alongside Merry. (Hm, if you switch a few sounds around, the name “Clara” even sounds vaguely like “Paraclete”… No, I admit, I’m probably reaching at that point! Still… considering her so-far three iterations, Clara, not unlike the Holy Spirit, certainly seems to bloweth where she listeth!)

As much as I like Clara, I suspect she fits the stereotypical companion profile more than either Oswin or Victorian Clara do. Watching her sit on the stairs, another “girl who waited” for the Time Lord to show up, makes me remember to the passivity I felt from her last week. And while I like her initiative in “exploring” the bazaar (even if her involvement in Merry’s life has some unintended consequences—though I suppose involvement with other people always carries that risk), I find myself wondering what, if anything, we should make of the fact that her sacrifice of a valuable object saves Akhaten. I understand Clara’s offering of “the most important leaf in human history” (one of the nicest uses of a prop in modern Who) is a selfless gift. It is “in character” for her. But is she anything more than a selfless giver? While selfless giving, to the point of self-sacrifice, is undeniably a Christian virtue, following the example of our Lord, who gave of himself “to the point of death—even death on a cross” (Phil. 2.8), this episode seems to define Clara almost exclusively in such terms. Too often, in art as in life, women are expected to be always the ones who give, without complaint, even if “for the greater good.” I don’t want to see too many Clara stories in which she conforms to that stereotype.

As much as I like Clara, I suspect she fits the stereotypical companion profile more than either Oswin or Victorian Clara do. Watching her sit on the stairs, another “girl who waited” for the Time Lord to show up, makes me remember to the passivity I felt from her last week. And while I like her initiative in “exploring” the bazaar (even if her involvement in Merry’s life has some unintended consequences—though I suppose involvement with other people always carries that risk), I find myself wondering what, if anything, we should make of the fact that her sacrifice of a valuable object saves Akhaten. I understand Clara’s offering of “the most important leaf in human history” (one of the nicest uses of a prop in modern Who) is a selfless gift. It is “in character” for her. But is she anything more than a selfless giver? While selfless giving, to the point of self-sacrifice, is undeniably a Christian virtue, following the example of our Lord, who gave of himself “to the point of death—even death on a cross” (Phil. 2.8), this episode seems to define Clara almost exclusively in such terms. Too often, in art as in life, women are expected to be always the ones who give, without complaint, even if “for the greater good.” I don’t want to see too many Clara stories in which she conforms to that stereotype.

“A Soul’s Made of Stories”

In “Bells” we saw people’s “souls” uploaded to the Great Intelligence’s creepy cloud. In “Rings” souls are once more at stake. This time, the people of Akhate (human and non-human alike—as a friend with whom I watched remarked, they’re very much a Mos Eisley cantina-esque bunch) are willingly offering their souls to feed the “Old God,” also known as “Grandfather.”

(Incidentally, since one of the few classic Who stories I’ve seen is “An Unearthly Child,” I had nerd excitement when the Doctor mentioned having been to Akhaten “once, long ago, with [his] granddaughter.” His line threw me off the scent, though; I spent much the first twenty minutes wondering whether the Old God might turn out to be the First Doctor! If, as River Song complained in “The Pandorica Opens,” old wizards in legends “always turn out to be him,” why not ancient dieties from creation myths?)

I liked the Doctor’s definition of souls as stories: “A soul’s made of stories, not atoms.” It turns out this sentiment isn’t original; the poet Muriel Rukeyser said much the same thing about the universe. But the Doctor’s version brings the point home in an intimate way. Our inner universe, our most immediate sense of identity, is composed of the narratives we hear and tell about and live out with each other and ourselves.

Christian faith takes seriously the formative power of story. This assertion will not strike any sci-fi Christians as breaking news, of course, but it never hurts to remind ourselves of the fact. A member of the weekly Bible study group in which I take part is fond of saying, “When we want answers from God, God tells a story.” We hear God’s story and, by faith and grace, come to see where we belong in it, and who we are, as individuals and as the community of God’s people, because of it.

Singing the Wrong Song?

Of course, as I’ve said before, there are good stories and not-so-good stories. Clearly, viewers are meant to conclude, as does the Doctor, that the story little Merry is living in accordance with, the sum of all the stories and legend and lore that her society has poured into her (I wonder how that works, exactly?) is a not-so-good story, to say the least! The story of the Old God would lead to Merry’s destruction and, as the Doctor says (in the script’s absolute highlight of a speech), “There is only one Merry Galel and there will never be another. Getting rid of that existence isn’t a sacrifice, it is a waste!”

Of course, as I’ve said before, there are good stories and not-so-good stories. Clearly, viewers are meant to conclude, as does the Doctor, that the story little Merry is living in accordance with, the sum of all the stories and legend and lore that her society has poured into her (I wonder how that works, exactly?) is a not-so-good story, to say the least! The story of the Old God would lead to Merry’s destruction and, as the Doctor says (in the script’s absolute highlight of a speech), “There is only one Merry Galel and there will never be another. Getting rid of that existence isn’t a sacrifice, it is a waste!”

I’m not a therapist, but I’ve heard some talk about a process called narrative therapy, in which patients are led to address their issues by reframing the stories they tell themselves about themselves. The Doctor practices a bit of narrative therapy with Merry:

Do you mind if I tell you a story? One you might not have heard. All the elements in your body were forged many, many millions of years ago in the heart of a faraway star that exploded and died. That explosion scattered those elements across the desolations of deep space. After so, so many millions of years, these elements came together to form new stars and new planets. And on and on it went. The elements came together and burst apart forming shoes and ships and sealing wax and cabbages and kings, until, eventually, they came together to make you.

The Doctor is right to impress upon Merry the miracle of her life (my word, not his). She needs to hear this truth of her precious existence and unrepeatable identity. None of what I’m about to say takes away from my commendation of the Doctor’s intervention. “Grandfather” is, as the Doctor calls it, “just a parasite,” obviously unworthy of Merry or the Chorister’s or anyone else’s service and worship.

I couldn’t help but feel, however, that the episode’s attack on this false god is ultimately, if not an attack, than a thinly veiled challenge to all religion (not unlike “The God Complex”). The script goes the Star Trek V route—“This is not the god of Sha Ka Ree, or any other god!”—but I infer from it an assertion that the Doctor’s “story” automatically and self-evidently trumps any story of faith. Why? Because the Doctor’s story conforms to scientific canons of truth. When Clara asks the Doctor whether, as the people of Akhaten believe, all life in the universe originated within their system, the Doctor gives a kind but unmistakable negative answer: “It’s what they believe. It’s a lovely story.” Lovely, but not worth building a life upon.

I couldn’t help but feel, however, that the episode’s attack on this false god is ultimately, if not an attack, than a thinly veiled challenge to all religion (not unlike “The God Complex”). The script goes the Star Trek V route—“This is not the god of Sha Ka Ree, or any other god!”—but I infer from it an assertion that the Doctor’s “story” automatically and self-evidently trumps any story of faith. Why? Because the Doctor’s story conforms to scientific canons of truth. When Clara asks the Doctor whether, as the people of Akhaten believe, all life in the universe originated within their system, the Doctor gives a kind but unmistakable negative answer: “It’s what they believe. It’s a lovely story.” Lovely, but not worth building a life upon.

I don’t want to protest this point too loudly or too long. I don’t need my entertainment to reinforce my personal beliefs or my faith tradition. I’m not surprised that science fiction, of all genres, would privilege reason over religion. I won’t deny that stories of faith, including the Christian story, can and have been perverted into life-denying, soul-eating, parasites more deadly than “Grandfather” itself.

I would only add that it need not be so! Belief in God doesn’t have to preclude an awe in the face of the universe as it is; in fact, I think belief in God demands it! If we don’t, with the psalm-singer, speak in flabbergasted, gobsmacked tones to God as we “look at your heavens, the work of your fingers, the moon and the stars that you have established” (Ps. 8.3), then we aren’t really worshiping the Creator. And, as the psalms also demonstrate, this sense of wonder in the face of the universe actually enhances, rather than diminishes, a sense of wonder in the face of humanity. The psalm-singer asks God, when confronted with the cosmos in all its beauty, “What are human beings that you are mindful of them, mortals that you care for them?” (8.4). And yet God does! The same divine artistry on display throughout the universe is manifest in the marvel of humanity: we are “fearfully and wonderfully made” (Ps. 139.14). The biblical teaching that we have been placed only “a little lower than God… [and given] dominion over the works of [God’s] hands” (Ps. 8.5-6) is not, properly understood, cause for boasting, but only further impetus to praise.

Yes, the universe is vast and wonderful and astonishing. And, yes, every human life is valuable and unique, all the more so because we are—even through the process of stars sputtering into darkness before blazing again to new life—created in the image of God. These affirmations can be sung in the song of Christian faith, especially given that the God who fashioned it all also hallowed it all by entering into it in Jesus Christ (John 1.1-5, 14).

Why is it, then, that so many creative and intelligent people, such as those who bring us Doctor Who, think the songs of faith and reason, the stories of spirit and science, can’t coexist—no, more than that, can’t complement each other?

Friedrich Nietzsche is supposed to have said, “They would have to sing better songs for me to learn to have faith in their Redeemer; and his disciples would have to look more redeemed!”

Might stories like “The Rings of Akhaten” be posing a similar challenge to us sci-fi Christians today?

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version, except where noted “CEB” (Common English Bible).

You bring up an interesting point about the sacrifice being an object.

In my own review, I mentioned that the Doctor let the old god take his memories . . . but they weren’t actually TAKEN. The Doctor still has them.

And that leaf? She sacrificed the object, but not the memories the object actually represented. She still HAS those. She gave up very, very little. In fact, thinking about it now, I would hardly even think of that as a sacrifice at all!

Maybe the idea of the old one taking the memories and potentials stored within that leaf is sound . . . but the climatic impact of this on the story, when held up to scrutiny, is not earned. “Hurry! Send that GOD away with a leaf you’ve kept for twenty years! Don’t worry, you get to keep everything the leaf represents!”

“As much as I like Clara, I suspect she fits the stereotypical companion profile more than either Oswin or Victorian Clara do.”

I’ve honestly been expecting her to die and for him to find ANOTHER one somewhere. I’ve been hoping that she wasn’t just a “special person” but some sort of entity that has been placed through space and time to be where the Doctor needs her to be.

I was waiting for this to happen in the first episode as well. Then I thought maybe she was another TARDIS in human form…..or even the Doctor’s daughter’s daughter. The Master’s daughter?? I don’t know. But I do hope that Moffat has a really good explanation behind this GIANT mystery or I may end up feeling like I wasted my time.

Thanks for the comments, Ben. Your comment about the sacrifice not really being a sacrifice is well taken, and hadn’t occurred to me. On the one hand, it makes me feel better about Clara being called upon to “sacrifice”… on the other hand, yeah, it kind of undercuts the whole resolution (which, I think, is fairly weak to begin with).

I hope Clara is Clara, and not an entity or a living meme or something like that, but we all know we are not done with the mystery surrounding her – the look on the Doctor’s face at the end, as he closes the TARDIS doors, make it clear that he’s not going to stop thinking about her connections to Oswin and Victorian Clara. Nor should be… but, there again, we have the episode working at cross-purposes. For all that I *do* think she’s more of a person in this episode, and that’s all for the good, I don’t want the mystery dropped, either; and I expect she’ll be remembered more as “the impossible woman” than any unique individual.

Huh – the Doctor’s whole speech about individuality – “There will never be another you” – how does Clara prove or disprove his point?

I feel like this episode needed more time in the oven…!

“Huh – the Doctor’s whole speech about individuality – “There will never be another you” – how does Clara prove or disprove his point?”

That’s RIGHT!!!

Holy cow!

I was honestly just asking. If the Doctor is right (and he usually is, in the end), then Clara, as she asserts at the episode’s end, is *not* Oswin and is *not* Victorian Clara (what was her nom de governess ? I forget). See, the episode maybe should have tightened up that connection more: if the speech is true for Merry Galel, it must be true for everyone, including Clara Oswald.

So, let’s go with the assumption that Clara is Clara and only Clara. Who, then, are the other two Claras? Are they also their own unique individuals? That would be straightforward, but not very “Doctor Who”-y.

It’d be fun if they’re out there, galavanting around the universe, bumping into Claras all over the place, and then in the season finale, it turns out Clara fell into a clone machine or something. Just something super straight forward as they are clones of Clara, lost in time. So none of them ARE Clara, but they’re all sisters.

I completely agree with Ben’s first comment. At first I was freaking out thinking Moffat was really going to take the Doctor’s memories of Rose and the Ponds so that he could start out ‘fresh’ for a new season with Clara.

But then… I was completely confused. The grandfather ate the Doctor’s memories but the he still retained them?? I don’t think that is scary at all. Heck, come eat my memories if I still get to remember it all afterwards, don’t think I would mind much. And then a simple leaf stopped the grandfather.

I thought it was all completely anticlimactic. So, if I am missing something, let me know.

Hi, Alyssa – It’s funny, it never occurred to me the Doctor would really lose his memories, even while he was letting Grandfather feast on him. That’s why Ben’s observation didn’t occur to me. He and you are both absolutely right – it’s a pretty sloppy resolution. I don’t think you’re missing a thing.

Thanks for reading and commenting, as ever!

” At first I was freaking out thinking Moffat was really going to take the Doctor’s memories”

Me too! Although I was thinking it’d be an interesting and monumental twist.

Very well thought-out and thorough analysis, Michael!

The only thing I would add or change is that the science fiction shows don’t *really* prefer “reason” over religion. They cling to the tenets of evolution even when evolution makes no sense. They have nothing short of a religious fervor for their so-called scientific beliefs. Meanwhile, as C.S. Lewis demonstrated over and over in his writing, Christian faith is actually deeply reasonable and logical.

That’s probably what you meant; it just didn’t entirely come across to me. 🙂 Keep up the great work!

Hey, Tom – Thanks for taking the time to read and comment; I appreciate it!

I agree faith is reasonable, else I wouldn’t waste my time with theology; on the other hand, faith is also an ultimate trust that can’t be empirically verified or proven through a series of logical propositions (else it wouldn’t be faith). I think it’s a gift of God, and why some have it and others don’t is a mystery. But I certainly didn’t mean to imply faith, once given, can’t be reasonably articulated, nurtured, and defended.

Would love to hear from you again as this “Who” season marches on!

I found this a little bland and only really chirped up when I heard the reference to his granddaughter.

And that was, what, like five minutes in? Must’ve been a long episode for you!

It was sooooooo long.

I played some Temple Run 2 (my preferred version), thumbed through some books, texted, brushed my teeth, made a scale model of Cinderella’s castle, balanced the U.S. budget, got a tatoo, and grew and shaved a beard all in the time it took me to watch this espisode.