What’s your favorite Christmas movie? Chances are your choice is self-evident—a seasonal standard like Miracle on 34th Street or A Christmas Story. Not many people would pick either of two science fiction films that debuted on this date, December 7, five years apart: Star Trek: The Motion Picture (TMP) (1979) and 2010 (1984).

It’s true that neither movies sparkles with traditional Yuletide trappings: no trees festooned in tinsel and glass balls, no colorful candy canes or drifting snowflakes, not a single sign of Santa. As far as viewers can tell, neither one even takes place around Christmastime. The bulk of the action in both doesn’t even take place on Earth!

Neither movie tops most folk’s lists of favorite films, sci-fi or otherwise, Christmas or otherwise. But both reward repeated viewings; and their shared December release date, while simply a calendrical coincidence, suggests both can be seen as “Christmas movies”—when considered from a theological point of view.

Humanity and Divinity

Yes, those are Orson Welles’ sonorous tones summarizing the plot of TMP. It was an early Christmas present and then some to thousands of devoted, first-generation Trekkies who’d been awaiting the starship Enterprise’s return for a decade. The film brought in the mass audience, too; it dominated its December box office, grossing more than $39 million in three weeks (about $97 million in today’s money).

I doubt few fans, if any, thought they were watching a “Christmas movie.” Theologically, however, Christmas celebrates the union of the divine and the human in the birth of Jesus. TMP, too, celebrates that miraculous union—albeit in a distinctly Star Trek sense.

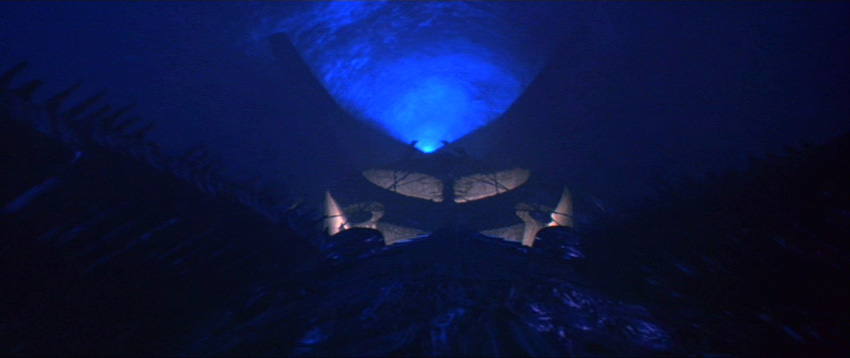

As that Orson Welles comerical suggests, V’Ger is the film’s “God” (in fact, one of the earliest versions of what would become the film’s story was titled “The God Thing”). V’Ger is vast and powerful, capable of evoking both awe and terror; it is Rudolf Otto’s mysterium tremendum et fascinans (fearful and fascinating mystery) in 70-millimeter cinematic glory. The Enterprise’s (lengthy) flight into V’Ger could suggest a pilgrim’s entrance into a soaring cathedral, especially since Jerry Goldsmith punctuates the score with the strains of a pipe organ. And this particular view of V’Ger’s interior has always reminded me of the cherubim atop of the Ark of the Covenant, further reinforcing a sense that we and the Enterprise are exploring an inner sanctum:

In some respects, then, V’Ger is “godlike,” but—as with all beings worshiped as and/or claiming to be divine in Star Trek—it is not God. Thirty-five-year-old spoiler alert: V’Ger is the highly evolved form of Voyager Six, a centuries-old (and, sadly, fictional) NASA probe whose transformation was sparked by its close encounter with alien, living machines on the far side of a black hole. It is a creature in search of its creator. Or, as Spock recognizes, it is a needy child:

Where the true God, in the Christmas miracle, “invades” Earth and joins with humanity as a child in order to save it, V’Ger is already a child, invading in order to join with humanity, “to join with the creator,” that it, V’Ger, might be “saved.”

Theologically speaking, then, TMP exalts humanity too highly. In this film, we are not the fallen people Scripture and experience tell us we are; we are instead necessary to “divinity” because we can provide what it lacks. “What V’Ger needs,” says Kirk, “is a human quality.” Specifically, V’Ger the machine needs humans’ intuition and imagination—“our capacity to leap beyond logic.” Kirk later expands on what makes humans special: the ability to create a “sense of purpose, out of our own human weaknesses, and the drive that compels us to overcome them.” Human beings in TMP aren’t perfect, but they’re much closer to it than most Christian teaching holds us to be.

Still, TMP does conclude with a beautiful “nativity scene.”

Afterward, both Spock and McCoy explicitly refer to the event as a birth. Because of this birth, this union of “divinity” and “humanity,” people can look toward the future with hope. As the film’s tagline asserts, “The human adventure is just beginning.”

While Christians’ views of the human adventure may differ from Gene Roddenberry’s, we can say, also, that a birth uniting humanity and divinity changed everything, giving us ultimate hope for our future—and not only ours, but the whole creation’s. And we can also affirm the necessity of overcoming “our own human weaknesses.” We can make common cause with those who work to improve our society and the world. The Son of God’s birth into this world hallowed it, and motivates us to seek the good of all the brothers and sisters with whom Jesus shared flesh and blood (see Hebrews 2.11-14).

Let There Be Light

Five years after TMP, many moviegoers were looking forward to 2010, too. A sequel to Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke’s epochal 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), 2010 follows a joint American and Soviet mission to Jupiter and its moons, where the derelict spaceship Discovery, its deactivated and potentially dangerous master computer HAL 9000, and the giant Monolith through which astronaut David Bowman all await.

As I stood in line to buy my tickets, a man in front of me told his friend, “This movie’s for people like me who were too stupid to understand the first one!” I doubt its creative team ever pitched the film that way, but 2010 is undeniably more conventional than its mind-blowing predecessor. That fact that may help explain its less than phenomenal receipts ($40.4 million over two months, or about $90.6 million now). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction dismisses the movie as “devoid of both narrative thrust and any interaction of characters that transcends cliché… a lot less magical and delicate” than the original.

I think 2010, like TMP, is far better than most people make it out to be. No, it is not the seminal masterpiece 2001 is. Granted, its characters tend toward the cliché—especially most of the cosmonauts, which is too bad; in Clarke’s novel, they are fairly fully developed individuals, whose relationships with their American colleagues feel rich and real. (Only Helen Mirren as Captain Kirbuk, one of her earliest film roles, shows any real depth—would one expect any less from Helen Mirren?) And, as a film, it usually looks more like a made-for-TV movie than a spectacle conceived for the big screen. (It even ignores its own predecessor’s startling commitment to scientific accuracy in that it adds sound to scenes set in the vacuum of space.)

But 2010 does achieve some impressive moments of beauty. The early, establishing shot of an antenna array, all those dishes pointed skyward, is one. The engrossing depiction of the surface of Europa is another. David Bowman’s mysterious and fleeting visitation as a herald of good news to Dr. Heywood Floyd is yet another.

But it’s the climactic transformation of Jupiter into a sun for the Jovian moons that helps me think of 2010 as a Christmas movie. In the book, Clarke dubs the new sun “Lucifer,” which means “light-bringer.” I wonder if he thought he was tweaking Christians and others who associate the name with Satan. But it’s not a name ever directly applied to the Devil in Scripture; and the new light’s positive consequences, especially in the film version (where it goes unnamed), are what endure.

While the astronauts and cosmonauts are in Jovian space, their respective governments on Earth are heading inexorably toward war. (2010 got the Soviet Union’s continued existence wrong, but turns out to have been prescient in predicting that tensions between America and Russia would still be with us in the early 21st century.) But Jupiter’s implosion, accompanied by a message from the unknown alien intelligence responsible for the Monoliths, causes the nations to make peace. How can Christians not think of the appearance of a new star in the east that announced the birth of the Prince of Peace?

In that message to his young son back on Earth, Dr. Floyd’s discussion of the significance of the new star—“You can tell them that you remember when there was a pitch black sky, with no bright star, and people feared the night. You can tell them when we were alone, when we couldn’t point to the light and say to ourselves: ‘There is life out there’”— evokes the prophecy of Isaiah so often heard in Advent and Christmas: “The people who walked in darkness have seen a great light; those who lived in a land of deep darkness—on them light has shined” (Isaiah 9.2). It echoes, too, the cosmic perspective of the Gospel of John’s prologue, as the evangelist unfolds the mystery of the Incarnation: “The true light, which enlightens everyone, was coming into the world” (John 1.10).

And while Floyd never indicates he is a religious man, his last words to Christopher (the name means “Christ-bearer”)—“Everyone looked up and realized that we were only tenants of this world. We have been given a new lease and a warning from the landlord”—make me wonder whether he believed “the landlord” is the alien entity orchestrating Jupiter’s ignition, or the God who, Christians believe, rules over all life, human and whatever alien life may exist? At Christmastime, 2010 can remind us that the Bethlehem Star tells us we are not alone, because Emmanuel, God-With-Us, is born (Matthew 1.23). The true light has entered the world, and we are to live as lights in the world as a result.

Your Suggestions?

This December, by all means keep watching Clarence talk Jimmy Stewart down from that bridge, or Linus recite Luke 2 in the school auditorium, or Scrooge wake up on Christmas morning a changed man. But try watching TMP or 2010—or both—in a Christmas frame of mind, too. They may just serve as cosmic parables of the deep mystery to which this season points.

And if you have a favorite science fiction film that also makes for unexpectedly appropriate holiday viewing, let us know about it in the comments below. Maybe you’ve discovered the next great cosmic Christmas movie!

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version.

Of related interest, check out Ben De Bono’s review of 2010, the novel.

This is a fabulous post, Michael. I love these two movies as well, but my appreciation for them took a long time to come.

Your Christmas lens is pretty convincing. I think a lot of believers have felt antagonized by Star Trek stories like TMP or The Final Frontier. But you’ve deftly skirted the issue by redirecting us to the inscrutability of God. You’d fit right in with the mystics!

Thanks, Mickey! I’ve liked 2010 from the word go, but I used to be one of those Trek fans who didn’t enjoy TMP all that much. I find my appreciation of it only grows with each viewing. Yes, the characters are “off,” but that’s part of the point: in its own way, TMP is an “origin story” (not surprising that it came out of the pilot episode for the Phase II series). TMP is about this crew “earning” their continuing mission. In that respect it’s not all that different from ST09: these are the people who will become (or, in TMP’s case, must become again) the people we know. I realize why that’s frustrating for some viewers, but it really is more interesting. Oh, well. It’s a lost cause to argue this movie’s merits, but I try anyway, even if I’m only preaching to the choir.

I probably, on reflection, should’ve given 2010 its own separate article – I think most folks aren’t getting past TMP 😉

Reading The Lost Years was fundamental to my judgment changing on TMP. Watching TOS and jumping to the movies was always so jarring. But seeing the movie in context, thanks to the novel, helped me to enjoy it a little more. And, strangely enough, seeing the movie in context helped me to watch it out of context and just enjoy it for its own sake. As a work of visual art, it’s pretty gorgeous.

My old roommate called TMP the only Trek movie that’s truly about exploration and I find that assertion a little hard to disagree with.

As for 2010, its attempts to fit in with the previous film are a little hacky (I mean the Strauss music playing loudly at the front and back of the feature). But as a visual appendix to the nearly excellent novel, I like it. Also, Scheider gives a great performance, even if it’s against such crass Russian stereotypes. (McGyver’s boss, in the SETI field at the beginning is so bad, it’s like he practiced by listening to a Yakov Smirnov record.)

And again, thanks for writing this piece. I’ve been doing more theology and less sci-fi lately and it was great to hop back into the field.

I read “The Lost Years” a long time ago and don’t remember one thing from it! I vaguely recall it addressed Spock leaving to go do Kolinahr. Maybe I should check it out again.

Star Trek V is also truly about exploration (albeit Sybok is the impetus for the exploring). It doesn’t fare any better than TMP in popular judgment. Maybe the mass public doesn’t really want to see these characters boldly going anywhere new any more (I like ST09 and have soured on STID, but can honestly say neither one is about exploration).

Last year we did a series about unusual Christmas movies, often with a sci-fi bent (although some of them, like Psycho and Citizen Kane, had no sci-fi Fantasy elements).

This year it’s been a bit harder to keep the schedule, although I do have another 24 movies selected for this year.

http://strangersandaliens.com/category/christmas-2/strange-christmas-movies/

Interesting choices! “Fascinating,” someone might even say. I look forward to seeing the rest of this year’s picks.