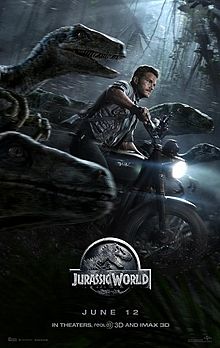

Jurassic World revisits Jurassic Park’s warning about meddling with nature, finding hints of hope amidst plenty of exciting, dino-caused carnage.

Jurassic World revisits Jurassic Park’s warning about meddling with nature, finding hints of hope amidst plenty of exciting, dino-caused carnage.

(Caveat Lector—This article contains SPOILERS)

At the book of Job’s climax, the LORD demands to know what right Job has to question God. “Can you draw out Leviathan with a fishhook,” the Lord asks, referring to an intimidating sea serpent, “or press down its tongue with a cord?” (Job 41.1). The LORD also points with pride to Behemoth, a powerful brute on land, “the first of the great acts of God—only its Maker can approach it” (40.39). The book argues that Job can’t judge God because Job can’t duplicate God’s ability to create and control massive, monstrous beasts.

But in this summer’s massive, monstrous hit film Jurassic World, human beings do both. They revive long-extinct dinosaurs and cook up a new one. And while these technology-derived tyrant lizards are ultimately their own masters, their relationship to human beings suggests we may not be as small and helpless in the face of overpowering forces as the book of Job suggests.

Surprisingly Original

Based on its trailer, I expected Jurassic World to be “little more than a remake” of 1993’s Jurassic Park. I admit, gladly, I was wrong!

Yes, this movie evokes more than one iconic moment from the original. During one sequence, in fact, it revisits the old park, now a heap of vine-covered ruins at the heart of Isla Nublar. But even that plot choice shows how the film’s creative team is interested in more than mere repetition. In-story, the old park’s physical presence must mean the people who built the new one (a full-blown, all-inclusive resort a la Walt Disney World) chose not to clear away the debris of previous failure, let alone learn from it. Instead, they ignore it. It’s kids who find and explore the wreckage of the past, and who, by jump-starting an old Jeep, salvage hope for the present from it.

Jurassic World includes several similar modifications on motifs from Jurassic Park. If it were a musical composition, it would be not a “cover” of a classic but “variations on a theme”—a perfectly legitimate art form, when done well. Jurassic World does it well.

Faltering On Family

The only major misstep the movie makes is trying to incorporate the original film’s concern with the importance of family. The two actors playing brothers Zach and Gray (Nick Robinson and Ty Simpkins) turn in serviceable performances, but their characters’ sketchy backstory hampers them.

As their Aunt Claire, Bryce Dallas Howard is hampered by more than the high heels she wears. Claire is ridiculed and derided throughout. Her sister Karen (Judy Greer) lectures her about why she should want to have children. Chris Pratt’s character Owen (about whom more in a moment) mocks her for wanting to actively help rescue her nephews. And those nephews dismiss her protection in favor of Owen’s (and for a quick, cheap moment of comic relief). Never mind that Claire leads a T-Rex out of its paddock in an authentically brave, game-changing moment. The movie reduces her to a woman who learns the importance of romantic and maternal love. I’m a fan of both, and not every female character in movies has to be Imperator Furiosa, but Claire, who should emerge as a heroic character, persists in the memories of viewers as a flat, borderline misogynistic caricature.

“Mad Science” Made Moral

The real star of Jurassic World is the Indominus rex—the genetically engineered dinosaur the park’s labs cook up to boost sagging attendance. It’s a thrillingly effective threat. It camouflages itself, courtesy of cuttlefish DNA in its makeup. It communicates with velociraptors, because it’s part raptor itself. It even hunts for sport—leading one to wonder if some human chromosomes lurk in its genome!

Indominus rex is the movie’s big, bad Frankenstein monster, the embodiment of all the dangers inherent in humanity’s attempts to “play God” through technology. “What we’re doing here,” insists Dr. Henry Wu (BD Wong reprising his 1993 role), “isn’t some sort of mad science.” Except that it is, just as it was two decades ago.

What is new this time is the part that “mad science” plays in saving what can be saved of the day. Owen is a raptor wrangler. He has trained them, treating them with respect because they are living animals—not raw resources simply waiting to be weaponized, or otherwise used (and abused) as humans see fit. Just as the first human being named God’s living creatures (Genesis 2.19-20), Owen names each of Jurassic World’s man-made raptors. It’s an act that shows he accepts responsibility for the way humans have manipulated natural forces. Turning back extinction’s clock is major manipulation!

Owen’s responsible stewardship reaps rewards. The raptors play a key part in tracking and bringing down Indominus rex. Owen has forged a partnership with the raptors that benefits both humans and human-made animals.

Jurassic Park argued that humanity shouldn’t meddle with nature. As Ian Malcolm (Jeff Goldblum) said, “Your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could that they didn’t stop to think if they should.” Two decades on, that question is moot. Jurassic World acknowledges that humanity has and will continue to meddle with nature. It invites us, instead, to address the urgent question of whether we will do responsibly.

We Christians are usually quick to recognize humanity’s limits. With Job, we “repent in dust and ashes” (42.6) when we transgress the boundaries God has set for our creative activities—and we should. But shouldn’t we also recognize, as this summer popcorn movie does, that preaching restraint is no longer enough? Can’t we learn something from Owen?

We humans have indelibly changed the well-ordered garden in which God set us (Genesis 2.15), and not always, or even mostly, for the better. That change will continue, with our without us. While we wait for God’s new creation, shouldn’t we work to help create glimpses of it in this one?

What did you think of Jurassic World? Let’s talk in the comments!

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version.

You make some good points in your article about how the movie lets down the Dallas Bryce Howard character – I don’t disagree. And the message of she isn’t a complete woman without children certainly plays into that. But I wonder if the scriptwriters would argue that they were only doing for her character what they did for the Sam Neil character in the original JP? He wanted nothing to do with children and, in fact, seemed mostly annoyed by them. But he’s the one who becomes close to them by the end, and, in fact, might even consider having some if he and Laura Dern’s character would marry? So for the sake of playing devil’s advocate (and to continue our film discussion ) I ask the question: how was her character in regards to children different in its portrayal than O’Neil’s was?

Thanks for the comments, Jeff, and for the great question. While O’Neill’s character did have a similar arc in the orignal film, (1) he was shown as a competent professional and a heroic person; his whole character identity wasn’t wrapped up in his attachment to or detachment from children, as Howard’s character’s is; and (2) it’s just different when a man is told he should want to be a father. Maybe it shouldn’t be, but it is. Everyone should be free to pursue children or not, as they see fit; but there is such a tradition of women being told children should/must be one of their goals, it’s more objectionable (to me, anyway) than hearing a male character being told the same thing. What do you think?