America loves conspiracy theories.

America loves conspiracy theories.

“Freaking out over imagineered shadowy plots,” wrote James Poulos for The Week last spring, “is one of our most durably American habits.”

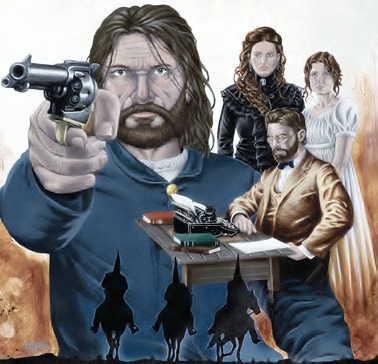

In his self-described “weird Western” novel The Man Who Shot John Wilkes Booth, author Kevin G. Summers (known for several acclaimed Star Trek short stories, and also a co-creator of and contributor to other shared worlds) reminds us that our country’s fascination with conspiracy is no new phenomenon.

Inspired by historical fact, focused on several compelling characters, and tinged with suggestions of the supernatural, Summers’ novel invites us to explore our attitudes toward not only conspiracies but also righteousness and truth.

Successfully Blending Fact and Fiction

Joshua Webb is a former soldier turned journalist. He writes and publishes the Paradise Ledger, the sole newspaper in the fledgling, fictional frontier town of Paradise, Colorado—“essentially a single street lined with businesses,” the archetypal late 1880s “Wild West” Main Street seen in scores of cowboy movies. But “there [are] shadows at the edges of Paradise,” and Webb makes it his mission to investigate them. He’s a postbellum Fox Mulder, a flawed hero who wants to believe the truth is out there.

So when Webb receives a letter from Sergeant Thomas “Boston” Corbett—an actual historical figure, who really did kill John Wilkes Booth and really was feted as a hero before being committed to an asylum for the insane about two decades later—he’s intrigued. Corbett promises to reveal “the truth of President Lincoln’s death… things that would make your heart sink into your bowels.”

Webb goes to Kansas to interview Corbett. He quickly becomes caught up in Corbett’s escape from the asylum and subsequent flight from the Society of the Cincinnati—one of three “infernal organizations vying for power” in America, Corbett claims, and the cabal that orchestrated Booth’s death at his hands. (The other shadowy movers and shakers are the Freemasons—no conspiracy theory is complete without them—and the Skull and Bones Society at Yale University. Jesuits eventually figure into the action, too. All unseen hands are on deck.)

The historical Corbett really did escape from an asylum, but his ultimate fate remains unknown. This gap in the historical record gives Summers an enviable amount of free rein and he uses it effectively, weaving a bizarre background for Corbett around some equally strange established facts (for example, Corbett castrated himself, probably for religious reasons). Summers creates a Corbett who is haunted by both sinister masters from his past and his vision of a wrathful, vengeful Christ; in fact, a tearful Corbett sees and hears Jesus addressing the parable of the sheep and the goats (Matthew 25.31-46) directly to him as the book reaches its climax.

“There was a Man who Believed In Truth…”

But the book’s title character—and we never forget who he is; one minor stylistic tic I didn’t like was the repeated use of the book’s title as a narrative tag—is arguably its least developed. I found Webb far more interesting.

Webb wrestles with his own theological and moral issues. When his prayers for his wife’s healing went unanswered, Webb lost faith in God. And Webb’s participation in General Custer’s massacre of a Cheyenne village at the Washita River shook his faith in himself: “They were casualties of war, so said General Custer, but Webb knew the truth. It was murder, and nothing he could say or do would ever change that fact in his heart.”

In part, a desire to atone for his sins drives Webb to publish the Paradise Ledger, but that choice, too, has painful consequences. Webb’s frequent trips in search of truth take their toll on his relationships with his 15-year-old daughter, Abby, and with the kindly Elizabeth McLarty, a widow with whom Webb is falling in love, as she is with him.

The book is strongest when it shows us Webb struggling toward a new sense of meaning and purpose. Readers will have to decide for themselves whether his conclusions about life, evil, and God are fundamentally hopeful or hopeless; but they are honest and hard-earned, which make them worth hearing.

New Voices from the “Old West”

Summers has a knack for writing suspense-filled action. While Webb is gone, nefarious agents of the Society of the Cincinnati threaten Abby and Elizabeth. The scenes in which Abby and Elizabeth must fend for their safety and lives are gripping and appropriately unpleasant; Summers conveys the danger without descending into unnecessarily lurid details. And Abby and Elizabeth aren’t merely present to be victims of male violence; both are well-developed characters with rich, inner emotional lives. (I especially appreciated and identified with Abby’s love of books.)

Ranse Shinbone is another character whose inner life we see, although not as fully. He and his wife Mercy are residents of “Browntown” (as Paradise’s white residents call it—not, the narrator tells us, “to be hurtful”), and they know from hard experience that Emancipation did not bring with it automatic inclusion in white society. During one especially tense moment, Ranse reflects that “there would never be a time when men did not hate him because of the color of his skin… [or] a time when trouble left him well enough alone.” Voices like Ranse’s aren’t always heard in the Western genre; I’m glad Summers included a secondary but significant black character in his cast. Perhaps, if future stories of Paradise follow, Ranse can play a larger role.

Conclusion

I found The Man Who Shot John Wilkes Booth enjoyable and satisfying. Summers is a confident storyteller, and this story engaged me from start to finish. It didn’t contain as much “weird” as I thought it might (although a pivotal scene shows us that abolitionist John Brown’s soul may quite literally be marching on). Nevertheless, it feels cloaked in that “certain atmosphere of breathless and unexplainable dread of outer, unknown forces” H.P. Lovecraft identified as a hallmark of “weird fiction.”

I found The Man Who Shot John Wilkes Booth enjoyable and satisfying. Summers is a confident storyteller, and this story engaged me from start to finish. It didn’t contain as much “weird” as I thought it might (although a pivotal scene shows us that abolitionist John Brown’s soul may quite literally be marching on). Nevertheless, it feels cloaked in that “certain atmosphere of breathless and unexplainable dread of outer, unknown forces” H.P. Lovecraft identified as a hallmark of “weird fiction.”

In Paradise, Colorado, those dread forces aren’t Lovecraft’s primordial monsters, but monsters that come from the human heart, monsters of greed and fear and hate that still stalk us today. These destructive powers are the real conspirators in The Man Who Shot John Wilkes Booth. The book acknowledges human evil—and implicitly asks each of reader what he or she intends to do about it.

Fans of Westerns and historical fiction, as well as Civil War buffs, should especially enjoy The Man Who Shot John Wilkes Booth. Because it contains some mature themes and language, I recommend it for older teens and adults.

Disclosure: Kevin Summers is a fellow alumnus of the Star Trek: Strange New Worlds writing contest, but he and I do not know each other. I received a free audio version of The Man Who Shot John Wilkes Booth through a giveaway at his website, but purchased the electronic text edition to write this review.

Leave a Reply