The sight of the Doctor’s hand moving the miniature TARDIS away from the train tracks in “Flatline” may be the weirdest sight Doctor Who has served up so far this season. (It’s certainly one of the funniest!) This week’s episode was full of strange sights, all of which underscored the Doctor’s assertion that we live in “a universe… immense and bizarre,” where we “cannot be too quick to judge.”

The sight of the Doctor’s hand moving the miniature TARDIS away from the train tracks in “Flatline” may be the weirdest sight Doctor Who has served up so far this season. (It’s certainly one of the funniest!) This week’s episode was full of strange sights, all of which underscored the Doctor’s assertion that we live in “a universe… immense and bizarre,” where we “cannot be too quick to judge.”

Fortunately for the people of Bristol—and, ultimately, for all of us in this plane of reality—the Doctor doesn’t mean we can never judge. Although he and Clara entertain several plausible interpretations of the extra-dimensional entities’ actions, he knows when he can and must judge and name “The Boneless” as the “monsters” they are. They are no utterly beautiful and unique, last-of-their-kind survivors: They’re invaders, out to get us, plain and simple. And, in the act of naming them, the Doctor names himself: “the man who stops the monsters.”

I think this episode gets us closer to what I hope is this season’s ultimate destination: the Doctor coming to terms with his identity, reasserting himself as humanity’s friend and defender (even if, as long as he wears this pre-frowned face, he’ll always think of us as pudding brains). Still, he’s not quite there yet, not when he’s telling Clara that “goodness has nothing to do with” being the Doctor.

Before the TARDIS touched down in that public housing estate, outsiders had apparently been ignoring the deadly goings-on there. The unfortunate man we see flattened in the teaser pleads with authorities over the phone, “Listen! Please listen!” (perhaps also a callback to the title of this series’ fourth episode?). Rigsby tells Clara, when he initially thinks she’s from the government, that he’s relieved “someone is finally paying attention.” And PC Forrest tells her superiors, with apparent agreement, that MI5 may think the local police “haven’t been doing enough” to solve the mysterious deaths. Doctor Who touched briefly on class issues earlier this season, when, in “The Caretaker,” Danny called the Doctor out on his upper-class superiority complex. Here, too, the show seems to be calling attention to class disparities.

Whatever the case may be in Bristol, it seems true in the U.S. that money means more access to society’s privileges and protections, including law enforcement. A 2006 article in the Boston University Law Review points out that “police protection is discriminatorily enjoyed by relatively wealthy areas.” Last year, following the discovery of the women kidnapped by Ariel Castro and held in a poverty-stricken Cleveland neighborhood, Syracuse University law professor Kevin Noble Maillard wrote, “Response time [of police] in wealthier neighborhoods far outstrips those of poor communities… It’s not entirely surprising that demographics influence access to public services. What is more surprising—and shocking—is the categorical [legal] protection of clear police ignorance, which puts police departments beyond reproach. Police are generally freed of responsibility for the citizens they are supposed to protect.”

Jesus’ story of the rich man who ignored the poor beggar Lazarus at his gate (Luke 16.19-26) sounds a warning not only to us as individuals but also to our society. We cannot allow wealth to keep us from paying attention to our neighbors on the margins, those those whose lives have been “flattened” by oppressive circumstances, those whom Jesus named “the least” members of his family (Matthew 25.40).

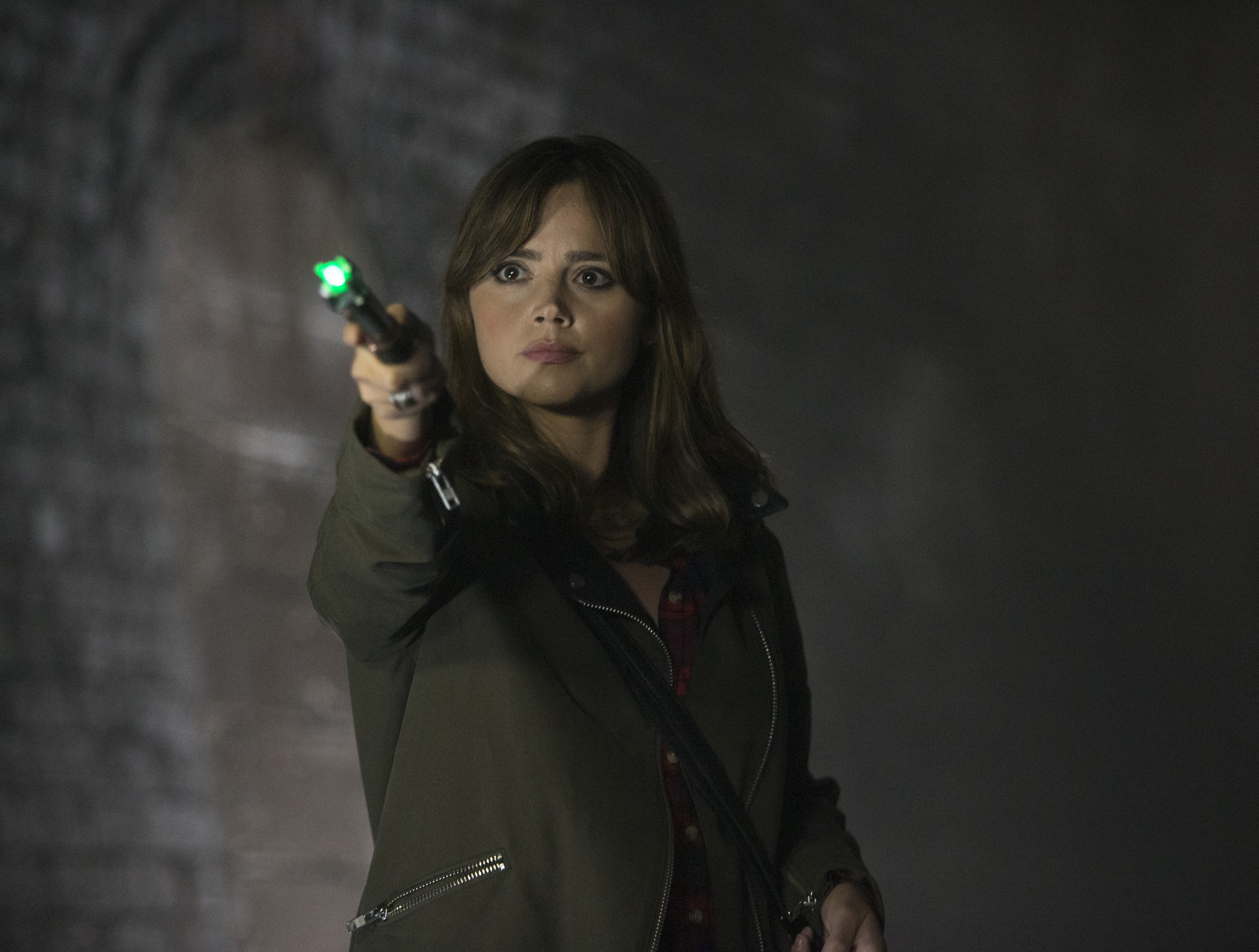

Playing Doctor

Clara proved she can take on the role of the Doctor. Like him, she can notice what others don’t, devise clever plans on the spur of the moment, take charge in a desperate situation, and inspire hope. What’s more, when she stops asking “What would the Doctor do?” and asks “What will I do?,” she takes a big step toward becoming “the hero of her own life” (as the quote on her whiteboard in “Kill the Moon” suggested she must). Even so, I’m uneasy about her imitation of the Doctor. Until “The Caretaker,” we knew a Clara who was already capable and heroic simply by being herself. Why has the Doctor—the same man who, in “Into the Dalek,” said he thought Clara must be an amazing teacher, and who still doesn’t seem to know who he really is—taken it upon himself to teach her a lesson in what being “the Doctor” means?

Clara proved she can take on the role of the Doctor. Like him, she can notice what others don’t, devise clever plans on the spur of the moment, take charge in a desperate situation, and inspire hope. What’s more, when she stops asking “What would the Doctor do?” and asks “What will I do?,” she takes a big step toward becoming “the hero of her own life” (as the quote on her whiteboard in “Kill the Moon” suggested she must). Even so, I’m uneasy about her imitation of the Doctor. Until “The Caretaker,” we knew a Clara who was already capable and heroic simply by being herself. Why has the Doctor—the same man who, in “Into the Dalek,” said he thought Clara must be an amazing teacher, and who still doesn’t seem to know who he really is—taken it upon himself to teach her a lesson in what being “the Doctor” means?

The longer Clara indulges her addiction to traveling with the Doctor, the more morally questionable she becomes. She lies to Danny, and lies about him to the Doctor. She lies to Rigsby and the other men—“for their own good,” the classic rationalization liars use. We’ve seen companions travel with the Doctor and maintain their moral compass; Clara herself did, when traveling with the Eleventh Doctor. Why is the Doctor now pulling her off course?

We have to be careful whom we imitate. Christians believe only one person is ultimately worth imitating. “Be imitators of me,” wrote the apostle Paul, “as I am of Christ” (1 Corinthians 11.1). Not even the early church’s most formidable missionary, influential theologian, and boldest evangelist claimed he was a role model except insofar as he was following Jesus. “Be imitators of God, as beloved children, and live in love, as Christ loved us and gave himself up for us, a fragrant offering and sacrifice to God” (Ephesians 5.1-2). The Doctor saves people, and coaches Clara to save people, by manipulating himself to a position of control: “You need to make sure that leader is you.” Jesus saves us by humbling and emptying himself in obedience to God’s will “to the point of death—even death on a cross” (Philippians 2.8).

Jenna Coleman delivered a fantastic performance as “Doctor Clara.” For Clara’s sake, though, I hope she’ll stop playing Doctor before it’s too late.

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version. As always, the positions I state in this essay are mine alone, and do not necessarily reflect those of other writers for The Sci-Fi Christian.

One comment on “TARDIS Talk: “Flatline” (Series 8.9)”