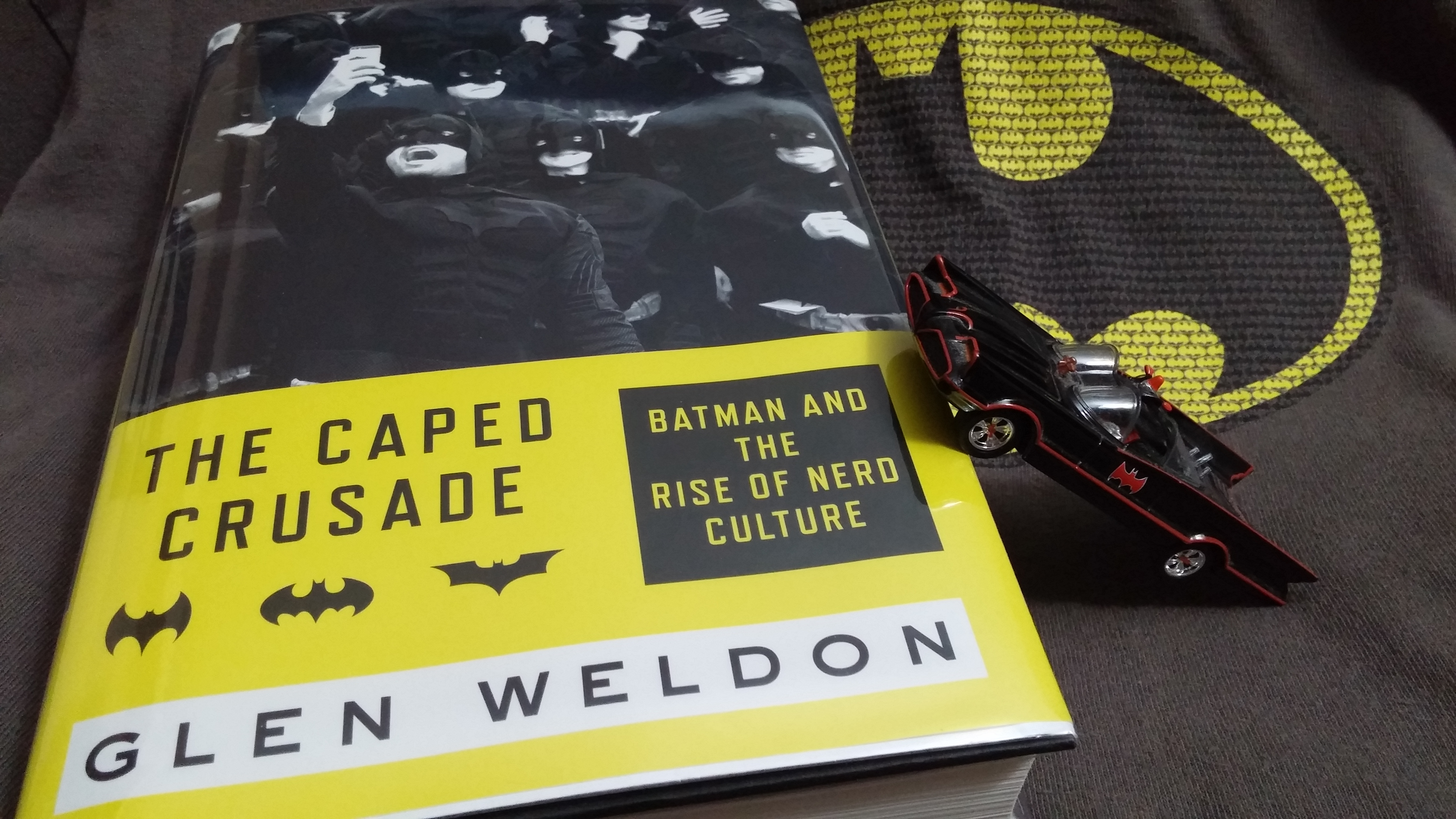

I was dreading Glen Weldon’s new book, The Caped Crusade: Batman and the Rise of Nerd Culture.

Not because Weldon’s a bad writer. He’s not; he’s outstandingly good. A movie, book and comic book critic for NPR and all-around bona fide pop culture expert, Weldon’s a smart, engaging, frequently very funny author.

When he brought all that talent to bear on Superman in 2011, I was thrilled. You can read my review of his Superman: The Unauthorized Biography and see: I thought the book was great. Of DC Comics’ first two superheroes, Superman is and always has been my first choice. Weldon’s account of the Man of Steel and his mythos was not only a good book in its own right but also felt like a validation, a vindication, when so much of pop culture has been all about the Bat for so long.

So when Weldon announced his next book would be all about Batman, too, I felt an irrational pang of betrayal. Et tu, Glen?

But I loved Glen Weldon’s new Batman book, from first page to last. I had such a good time with it, I started my second reading as soon as I finished my first. In fact, I probably enjoyed Weldon’s take on the Dark Knight even more than his take on the Man of Tomorrow (just please don’t tell Superman, okay?).

Things I Never Knew About Batman

Things I Never Knew About Batman

Maybe I enjoyed The Caped Crusade so much because it taught me a lot I never knew about Batman, and challenged a lot I thought I did.

- Batman wasn’t originally “grim and gritty.” At least not really, and not for too long. Weldon deftly dismantles received fan wisdom that Batman was doing just fine as a brooding loner prowling Gotham’s shadows until Adam West ruined it all by dancing the Batusi. “After all,” Weldon points out, “Batman had tangled with werewolves, vampires, and death rays even in his very first year.”

- Batman wasn’t all that original to begin with. “Nothing about the character was new,” Weldon asserts, and presents evidence that backs him up. What was new about this “crude, four-color slumgullion of borrowed ideas and stolen art” was the speed with which he entered popular culture off the comic book page (and Weldon wins extra wordsmithing points for introducing me to the word slumgullion; I’d have guessed it was the name of a crook in Batman’s rogue gallery).

- Sometimes, Bob Kane showed absolutely no shame. I was aware Kane downplayed and denied artist Bill Finger’s role as Batman’s co-creator, but didn’t appreciate how hard Kane worked to make sure the public saw him alone as the Dark Knight’s daddy. When the 1966 TV show was all the rage, Kane would “sketch” Batman in front of live studio audiences by tracing drawings that had been prepared by artist Joe Giella “beforehand in a light blue pencil that the television cameras couldn’t pick up.”

- Tim Burton was going to direct a Batman stage musical. Long-time listeners of the Sci-Fi Christian podcast will recall the Batman “live experience” Matt, Daniel and Ben endured so the rest of us didn’t have to. But at some point the Dark Knight was on course for the Great White Way, in an honest-to-Gotham book musical with splashy production numbers and catchy tunes. Weldon only mentions the musical in passing, relegating it to a footnote (see page 217); I’d love to know more. Will we ever get at least a concept album? (Of course, considering Spider-Man’s disastrous big Broadway adventure, maybe we’re all better off not knowing more…)

The 1960s Batman TV show wasn’t a parody, and Tim Burton’s 1989 Batman wasn’t dark. Once again Weldon upends conventional wisdom. Batman the TV series, he argues, was less an adaptation of the character and more a visual transliteration of the comics. As for the 1989 movie’s much-vaunted return of Batman to his shadowy roots? Not so much. Weldon shows how Batman is a 1980s action movie, not a Batman movie. “And any film that contains a scene like the one in which a bereted Joker defaces an art gallery while shaking his fifty-one-year-old moneymaker to Prince’s contractually required ‘Partyman’ can only make the 1966 television series look like Requiem for a Dream.”

The 1960s Batman TV show wasn’t a parody, and Tim Burton’s 1989 Batman wasn’t dark. Once again Weldon upends conventional wisdom. Batman the TV series, he argues, was less an adaptation of the character and more a visual transliteration of the comics. As for the 1989 movie’s much-vaunted return of Batman to his shadowy roots? Not so much. Weldon shows how Batman is a 1980s action movie, not a Batman movie. “And any film that contains a scene like the one in which a bereted Joker defaces an art gallery while shaking his fifty-one-year-old moneymaker to Prince’s contractually required ‘Partyman’ can only make the 1966 television series look like Requiem for a Dream.”

- Black actors got “nudged aside” when director Joel Schumacher took the film franchise’s reins. Why didn’t Billy Dee Williams reprise the role of Harvey Dent? Because Schumacher wanted Tommy Lee Jones. Similarly, Marlon Wayans was tapped to play a “tough, streetwise mechanic version” of Robin until Schumacher brought in Chris O’Donnell. Weldon doesn’t directly accuse Schumacher of racism, but these recasting incidents offer sober reminders that, like the 2015 and 2016 Oscars, #HollywoodBatmanSoWhite. (Weldon mentions Lucius Fox the character once, but not Morgan Freeman’s delightful portrayals of him in director Christopher Nolan’s films.)

Bat-Fandom: A Cautionary Tale

But I ultimately appreciated The Caped Crusade for more than the Batman trivia it taught (or re-taught) me.

First, Weldon makes an immediately compelling argument about what really makes Batman Batman. It’s not his physical prowess. It’s not his vast fortune (which Weldon, as have others, fingers as Bruce Wayne’s real superpower.) I’ll leave it to you to read Weldon’s book and find out what it is, assuming you don’t already know; perhaps other writers and fans have singled out Batman’s sine qua non before, but Weldon does it with gusto and grace, and demonstrates on several occasions how it keeps our hero on a meaningful quest instead of a personal vendetta.

Second, and most important, Weldon (as his book’s subtitle signals) concerns himself with not only the character of Batman but also the fandom—the unrelentingly rabid fandom—Batman has inspired. And this insight, more than any other, powers Weldon’s book, as surely as atomic batteries powered the TV Batmobile: Bat-fandom as we know it emerged almost entirely as backlash against the Adam West series.

If you never thought the 1966-68 series with its corny catchphrases, kooky camera angles, and crazy cameos mattered as anything more than (as Weldon says) a “gateway” to superheroes in general and Batman in particular— think again. Weldon makes his case clearly: “Until Batman’s premiere [on January 12, 1966], that virulent strain of devotion—the conviction that one’s love of a character entitles one to ownership of it—remained a sentiment in search of an outlet.” But when the ABC series proved a ratings smash, veteran fans of comic book Batman

could condemn the show and the hordes of fresh, fair-weather Batman fans it bred. They began to shape, for the very first time, the sentiment that all nerds who followed them would employ whenever they found their niche interests embraced by the mass culture: “You do not appreciate this thing you profess to love in precisely the same way, to precisely the same extent, and for precisely the same reasons that I do.”

Or, more simply, “You’re doing it wrong.”

The sickness Weldon diagnoses as nerd culture’s affliction is a strain of the same malady currently plaguing our larger society—a virulent variation on the old, intolerant theme, “We are unalike; therefore, you must be wrong.”

I confess I’ve felt that self-righteous indignation sometimes. I felt some twinges of it after watching Batman v Superman: “Harrumph. Wasn’t my Superman.” I felt more of it after watching Star Trek Into Darkness: “Harrumph. Not my Star Trek.” Yes, at times, I’m the Grumpy Old Fan, yelling at young whippersnappers to get off my lawn.

But in my better moments, I remember (eventually) that someone else’s way of enjoying characters, stories, or fictional worlds does me no harm. If anything, these narratives’ ability to spawn and sustain multiple versions testifies to their richness. No one is forcing me to forget “my” version—and if I tell myself they are, I’m only cheating myself out of the chance to try something new.

Where “nerdclinations” are concerned (to borrow Scott Higa’s wonderful word), very little is at stake. But when the same attitude creeps into personal relationships, public discourse, and politics, we drift into treacherous waters.

The nerd culture wars Weldon describes mirror the culture wars we in the United States have been fighting for decades. Increasingly unable even to tolerate those who are different from ourselves, much less take positive delight in diversity, we distance ourselves from and demonize others, telling ourselves and them that, because they aren’t just like us, they must be wrong.

Weldon’s nerd culture narrative does end on a hopeful note. Batman the Idea escapes the clutches of those who would keep him exactly as he was in 1938, or 1969, or 1986. “The world has accepted hard-core fans’ argument,” Weldon concedes. “Batman… is serious. And awesome. And definitely not gay. And, most importantly, now and forever, badass.”

But at the same time, more people than ever are enjoying Batman—through cartoons, through Lego Batman, through snarky Internet memes. Some people, at least, have found a way to let all Batmen be Batman—and, Weldon suggests, they’re having a better time than “true fans” ever will.

I hope we Americans will find a way to bring more of that all-embracing spirit into our relationships with each other. Certainly, our convictions matter. And those of us who are Christians believe some truths are non-negotiable; we are not to be like “children, tossed to and fro and blown about by every wind of doctrine” (Ephesians 4.14, NRSV). But living by one’s principles is no license to dismiss or threaten other people—real human beings, also created in the image of God, also sinners for whom Christ died—who disagree or who are simply different. If we speaking the truth in love (again, Ephesians 4.14), we aren’t cutting off conversation, or closing off relationships—we are encouraging them.

As we at The Sci-Fi Christian say all the time, stories matter. Our reactions to those stories matter, too. Glen Weldon’s new Batman book shows us two ways of responding to Batman’s story, and one is a heck of a lot more fun than the other—and reflects a more joyous, faithful and excellent way of responding not only to each other’s stories but also to each other in real life.

What version of Batman do you respond best to, and why? Let’s talk in the comments below!

(Ad from Action Comics #12 found at http://www.dialbforblog.com/archives/389/. Image of Burt Ward as Robin and Adam West as Batman found at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Batman_(TV_series)#/media/File:Batman_and_Robin_1966.JPG.)

Leave a Reply